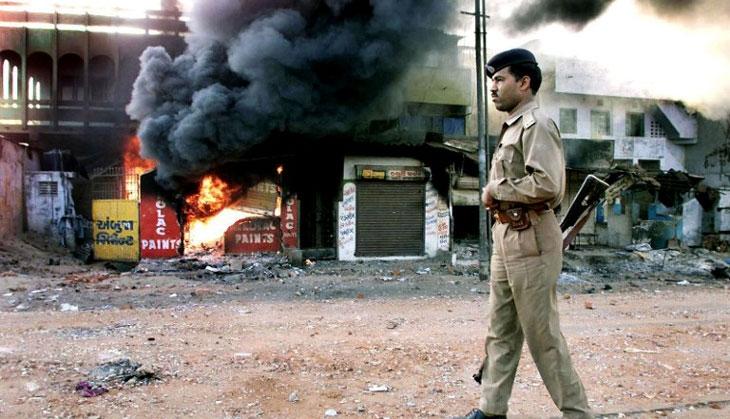

27 February, 2002, was a day that would change the landscape of Gujarat forever. While some may argue that the incidents at Godhra that fateful February were merely the culmination of a long, simmering build up, it was the events of this day that set in motion months of violence that would rewrite the state’s DNA.

As communal riots erupted across the length and breadth of Gujarat, State machinery was paralysed and the nation watched on as scores were murdered in waves of brutal violence that raged on for what seemed like eternity.

Scarcely 10 months on, Narendra Modi, the then-CM of Gujarat, his Hindutva credentials strengthened by the State’s apparent complicity in the violence, was re-elected in a landslide, despite months of lawlessness.

It has now been 15 years to those fateful events, Narendra Modi has leveraged that re-election to launch his political career to even greater heights. Maya Kodnani, who was convicted and sentenced to 28 years behind bars for her part in the riots is roaming free, having served scarcely two years of her sentence. Babu Bajrangi, another who was convicted for his involvement, has also been released on bail more times than one can count on their fingers, on various pretexts.

Meanwhile, Zakia Jafri, whose husband Ehsan was brutally slaughtered by rioters during the Gulbarg Society massacre, is still searching for justice. It’s a quest that is seemingly futile, and will doubtless plague the rest of her tormented existence.

However, despite the lack of reparations for those affected by the violence, the 2002 Gujarat riots have seemingly been relegated to pages of history, as evidenced by Modi’s unchecked rise to the Prime Minister’s seat. In fact, whenever the riots are brought up, those on the side of Modi have often called for the riots to be forgotten, touting his clean chit from the courts as the ultimate vindication of Modi’s tenure as CM during the violence.

In this interview with Catch, social activist Harsh Mander, who has worked since 2002 to obtain justice for the victims of the Gujarat violence, talks about why the violence cannot and should not be forgotten, and why Modi will never be absolved of the blood that stained Gujarat as a result of the riots.

These are the edited excerpts:

Ranjan Crasta (RC): Post-independence India is no stranger to communal riots. What sets the 2002 riots apart?

Harsh Mander (HM): 2002 is definitely part of a pattern of violence. I see post-partition communal violence in three broad phases. The first is up to Delhi, where we saw large episodes of communal violence with major harm being done to the minority communities, but there was some damage on both sides.

Then [in the second phase] we see large scale, straightforward brutal massacres of the minority community, with the almost open backing of the state, which ultimately culminated in the 2002 violence.

The third phase includes incidents like Muzaffarnagar, or even Kokrajhar, where the actual number of deaths is much lower, but there is a lot of displacement where the social divide is made permanent.

2002 has to be seen in the context of these various episodes, but there are a number of things that set it apart. I think one has to be the degree of cruelty. I have dealt with riots in the past, including the ’84 riots in Indore, but I have never encountered that degree of cruelty and violence targeting women and children.

While the complicity of the State is common in the 1984 riots and 2002, the ensuing refusal of the State to do any kind of rehabilitation, or even set up relief camps was significant. The open, brazen hostility and animosity towards the suffering community, displayed and continuing to be displayed by the head of government. When Mr. Modi was asked why he wouldn’t set up relief camps, he said he didn’t want to create baby-making factories.

I cannot recall another instance of this sort of contempt towards people who it is your constitutional duty to support. In fact, there was even a celebration of the violence in the [Gaurav] yatra that followed the violence. These things make 2002 distinct.

RC: The establishment narrative is that the violence was reactionary, but there is a lot of evidence that it was a planned escalation…

HM: The idea that the violence was reactionary is a problematic one, in fact, we shouldn’t call it the post-Godhra riots because it was more than just a riot and to say post-Godhra makes it seem like the violence was an understandable response to the initial incident. That is not the case. The idea that reactionary violence is, somehow, morally more condonable is problematic.

But the extent to which people [those involved] had prior preparation and specific information, something that went across more than 20 districts [is suspicious].The fact that people knew that in one mall in Ahmedabad, one shop had a sleeping partner who was Muslim, information like that.

Then you have the gas cylinders, availability of weapons, chemicals – the whole mobilisation, there’s a good deal of evidence that suggests the violence was planned.

RC: Supporters of Modi often remind us that he received a clean chit from the courts. Is this enough to absolve him of culpability?

HM: Absolutely not. There were enough problems with the SIT report that Raju Ramachandran (senior SC advocate) pointed out to the courts. The SIT report, at best, suggests that there is no irrefutable evidence that Mr. Modi gave direct instructions to allow the violence to happen. That is, at best, technical clearance because that sort of evidence is hard to come by.

But the happenings, the statements by the government, the fact that the violence continued for several weeks [indicate otherwise]. I have worked with the government, I know for a fact that no riot, however large, can go beyond a few hours if the State doesn’t want it to.

RC: In the run-up to the 2014 elections, we were told repeatedly to forget 2002 and move on, what are your thoughts on that?

HM: I think that we have no right to forget and move on till the survivors, who have suffered the violence, are ready to forget and move on.

I have learnt from many years of experience that there are four things necessary for victims of such violence to move on – acknowledgement (that they have been wronged), remorse (on the part of the State), reparation, and justice.

http://www.catchnews.com/india-news/15-years-pass-but-the-stain-of-2002-riots-will-never-leave-narendra-modi-52954.html

March 1, 2017 at 10:00 pm

The memory of the riots in Gujarat will not be erased until the victims of violence by the right wing hindutva forces is not investigated and guilty punished