The conflict between property rights and economic development is as intractable as ever

G Seetharaman | Lakhapadar, Lanjigarh, OdishaOur comfortable 30-km drive from the railway station in Muniguda in southern Odisha’s Rayagada district comes to an abrupt end as we take a turn into the woods. We manage to cover the first seven kilometres in our Bolero, but it takes more than an hour, as the driver navigates tricky potholes and breaks thorny stems through the window. He gives up after he sees a precarious ditch, which leaves us another four kilometres to cover by foot in the punishing mid-day sun.

We stop periodically to take in the beautiful vistas of the Niyamgiri hill range, and after roughly 45 minutes, we make it to Lakhapadar village, home to 30 families. There is a festival underway to honour their god, Niyam Raja, who is said to reside in the eponymous hills. As a couple of women dance to percussive beats, we are shown the buffalo that is to be slaughtered in a while.

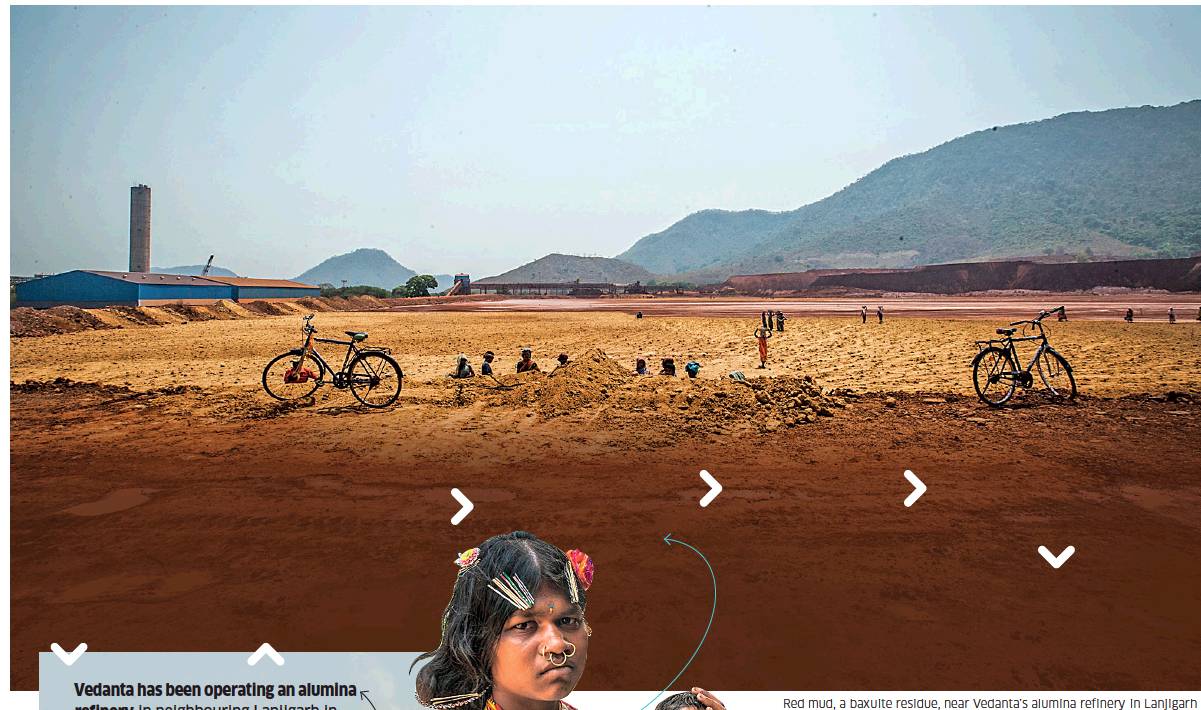

Peopled by the Dongria Kondh, a particularly vulnerable tribal group, Lakhapadar was one of 12 villages from the region that were in the news five years ago for unanimously voting against a project by state government-owned Odisha Mining Corporation (OMC) and Sterlite Industries (which is now Vedanta Ltd, listed on the Bombay Stock Exchange and the National Stock Exchange). It wanted to mine bauxite — the primary raw material for aluminium — from the Niyamgiri hills for Vedanta Aluminium’s 1 million-tonne-per-annum (mtpa) alumina refinery in neighbouring Lanjigarh, which had been operational since 2007.

The villages’ decision followed a landmark Supreme Court verdict on April 18, 2013. The court said forest clearance to the mining project, which had been withdrawn by the Environment Ministry in 2010, could be given only after taking the consent of the gram sabhas, or village councils, in the region. The judgment vindicated the decade-long movement, which had attracted international attention, given that Vedanta Ltd is an associate company of billionaire Anil Agarwal-owned Vedanta Resources Plc (FY2017 revenue: $11.5 billion), which is listed on the London Stock Exchange. The anti-mining agitation was also helped by the popularity of the 2009 film Avatar, which is about a ruthless mining corporation looking to extract a precious mineral from a moon inhabited by a humanoid species.

An attempt by OMC to convince the Supreme Court to hold gram sabhas for a second time was quashed in 2016. When asked if the government would try again to mine in the region, Lado Sikaka, a resident of Lakhapadar and one of the local leaders of the movement, says people here will not let that happen. “Let our blood flow like a river, but we won’t allow mining.”

Besides the Dongria Kondh, the Kutia Kondh, an associate tribe, and Dalits live in the 112 villages that would have been affected by mining. Last year, the Union Home Ministry said the activities of the Niyamgiri Suraksha Samiti (NSS), which was central to the agitation, were guided by Maoists, a charge members of NSS have denied.

While mining on Niyamgiri is unlikely in the near future, Vedanta sources bauxite for the refinery from within the country and through imports. “Post the 2015 amendment to the MMDR Act, natural resources will have to be auctioned. We are awaiting this development and will participate in the process once the auctioning starts,” says a company spokesperson. The MMDR Act is Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act. The refinery, on which the company has so far spent ₹10,000 crore (including on a captive power plant), has approvals to expand the capacity from the current 2 mtpa to 6 mtpa.

Law of the Land

The Niyamgiri case is one of the most infamous industrial projects plagued by land-related conflicts, alongside South Korean company Posco’s abortive steel project in Jagatsinghpur district in Odisha and Tata Motors’ Nano plant in Singur in West Bengal, which was later moved to Sanand in Gujarat.

Among the key legislation introduced by the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance during its 2004-14 rule were the The Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, and the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (LARR).

The Forest Rights Act (FRA) grants scheduled tribes and other forest dwellers the right to cultivate forest land (individual forest rights), collect and dispose of minor forest produce other than timber and use grazing land and water bodies (community forest rights), and protect and manage their forests (community forest resource rights). No project can be carried out in the forests without the approval of gram sabhas. The Supreme Court verdict in the Niyamgiri case was based on the rights of local communities under FRA.

LARR, which replaced the Land Acquisition Act, 1894, increases compensation to 2-4 times the average of registered sale deeds; recognises the claims of not just those who owned lands; and necessitates a social impact assessment (SIA) and consent of 80% of the landowners in case of a private project and 70% in a public-private partnership project.

The new law faced stiff opposition from industry and state governments so the Narendra Modi government, after assuming power in 2014, tried to exempt certain categories of projects like defence, infrastructure and industrial corridors from the SIA and consent clauses through an ordinance. But the government decided to let the ordinance lapse after it attracted widespread criticism.

Namita Wahi, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, calls LARR “poorly drafted” but says it gives rights to not just landowners, but also tenants and sharecroppers. “SIA is to establish everyone who will be affected by the project.” After the ordinance lapsed, states like Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Telangana amended LARR to achieve what some of the ordinance could not.

NC Saxena, a former Planning Commission member, calls LARR “pro-bureaucracy and pro-civil society and not pro-landowners or pro-industry”. A former chief executive of one of India’s largest infrastructure development companies, who requested anonymity, also bemoans the lack of a timeframe for acquiring land under the law. Saxena concurs by saying that it could take as long as four years to acquire just one acre. “The premise of the law is acquiring land is evil so it should be difficult.”

The former CEO says large infrastructure companies have stopped bidding for projects for fear of, among other things, being caught in a protracted land acquisition process. “Courts look at land acquisition disputes from a compassionate point of view rather than a developmental point of view.”

Jairam Ramesh, under whose tenure as Union rural development minister LARR was passed, dismisses these criticisms. “This is a crappy argument. Of course, it has added to cost and time and, rightfully so, to make land acquisition fairer to those who will be affected by it and also more democratic.” Ramesh was at the helm of the Environment Ministry when it rejected stage-II forest clearance to the Niyamgiri mining project, after a panel headed by Saxena submitted its report.

According to a study by CPR’s Land Rights Initiative, more than three-fifths of the cases in the Supreme Court related to Central and state land acquisition laws between 1950 and 2016 had to do with compensation. Wahi, who was the lead author of the study and heads the initiative, disputes companies’ assertion that the cost of land acquisition has increased substantially. The study states that courts have been awarding higher compensations than were offered by the government. In 445 cases, the Supreme Court offered compensation that was over 600% higher than the government’s.

According to Land Conflict Watch, there are 585 land-related conflicts in India, with investments totalling ₹13 trillion and affecting 6.7 million people. Hemant Kanoria, chairman and MD of Srei Infrastructure Finance, says even if a company wants to acquire land on its own, in which LARR does not apply, multiple clearances make investors and lenders wary. “Financial institutions dread funding such projects. It is an act of supreme bravery.”

Despite the passage of LARR, or perhaps because of it, conflicts and litigation related to acquisition continue to abound. Between January 1, 2014, when LARR came into effect, and December 31, 2017, the Supreme Court heard 322 cases related to the law, according to CPR’s Land Rights Initiative. (The Ministry of Rural Development did not respond to ET Magazine’s questions.) As the conflict between protecting land rights and promoting industrial and infrastructure development continues, some posit a different approach. “So far the model of development has been that some people have to lose so that others can benefit. Why can’t we have a model where no one loses?” asks Saxena. He adds that people belonging to tribes are ill-equipped to partake of the benefits of industrialisation, as they lack the requisite education and skills to get jobs.

Prafulla Samantara, an activist who won the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize for his role in the Niyamgiri movement, says development should not mean displacement for tribes. “We can’t say development is bringing them out of the forest. It should be based on their culture and livelihood systems. The government should help them process and market forest produce and set up food processing units.”

Allegations of air and water pollution by Vedanta’s alumina refinery in Lanjigarh notwithstanding (the company claims it follows pollution norms), it cannot be disputed that the area around the plant has benefited from good roads, housing, healthcare and schools. The Niyamgiri villages, on the other hand, do not have access to these. “Development for us is being able to protect our hills, rivers and jungle,” says Sikaka. He adds that they do not mind the government setting up basic facilities, but that should be with their consent and not come with riders.

In a country like India, where millions have been denied rights over the lands their families have lived and relied on for generations, it would be foolish to say economic development should take precedence at any cost. All the same, with not enough new jobs being created — likely a key issue in the 2019 general election — growth can scarcely be ignored. But, unfortunately, we are not any closer to striking a balance between the two than we were a decade ago.

April 17, 2018 at 4:19 pm

The court judgment had little impact. The people are still waging relentless struggles against mining corporates