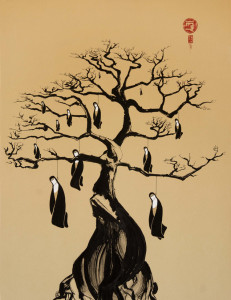

Hanging from a tree

We need a public, consumable, spectacle of remorse and penitence

Hanging bodies from trees is what white supremacists routinely did in the American South after the Civil War. Emancipated Black men were lynched and strung up like animals for the world to see. It was the sport of power. Slavery had been abolished, but the masters of a slave society were determined to crush the quest for liberation. These were not crimes in sense that we understand crime. For crimes committed under the cover of darkness, by stealth, signify something else entirely; they signify the existence of a legal and moral order, howsoever weak, that enforces secrecy and concealment; that forces perpetrators to slink away and hide. But these hangings were part of a public drum-beating semiotic of power; unspoken racial social laws enforced by terror.

Human to animal

Stringing up human beings, as opposed to simply beating them to death, was also a signifier of something else — of de-humanising and making carcass of the Black body. The victim was often killed by other means — shot, strangled, beaten, tortured to death. But the act was not complete until they were also converted to mere hanging carcass, hands and feet tied, swaying in the wind, exposed to the elements, a body profaned, stripped of the ceremony of dignity accorded to a human in death. Through this one simple act, the White master converted the Black human into animal, and trumpeted his complete power over it. Much like the hunter plants his heavy boot on the body of a dead tiger, and poses for the camera, revelling in complete submission of the beast. Or nails its disembodied head on a display trophy wall. For these are public acts, that have no meaning unless they are publically consumed. Those who do and those who watch are intrinsically part of the same codified messaging. The objective is display of the might of one, submission and subjugation of the other.

This is what has happened in Badaun in 21st century India. The consumption of the living bodies of two young ‘low-caste’ girls (in the act of gang rape) was completed by the consumption of their de-humanised, dead, subjugated, ‘low-caste’ bodies as public and media spectacle. The media came to town, as did a cavalier array of politicians. They all came, participated in a codified spectacle, looked up at the shamed tree, and left saying nothing.

The full meaning of what happened still seems to elude most of us. Instead we scramble for solutions like toilets for women. These two girls did not get strung up on a mango tree because of lack of toilets. They were strung up because, despite town criers hailing India’s first post-caste, post-identity election, the fact is that our entrenched hierarchal identities did not take a suicidal walk into the glory of an aspirational new dawn. They merely coalesced into new electoral shoals, now out for vengeance.

Public acts of humiliation and subjugation of ‘low’ castes are the norm in rural India. And the ‘low-caste’ woman-body, a site of multiple meanings (as unclean and forbidden, yet desired and easy object for upper-caste consumption, and site for vengeance and subjugation), is often the target. What is novel is that more and more of her screams are slipping out from the silenced hinterland, and piercing the urban eardrum.

Need for a maximalist response

Two ‘low-caste’ girls were hung on a tree like slaughtered animals. Yet the state system foot-drags and trots out the same minimalist responses with banal regularity — suspension of police officials, rape crisis centres and offers of compensation to the family. Where is the core of alarm in the moral body politic? Why not the maximalist response? Not mere suspension but criminal action to the fullest extent of the law against the rapist-hangmen and their police collaborators, full security to the family, to witnesses and the healing human hand of support for the long legal journey that lies ahead. And what of us, all who have watched this? “But even those who were only distant witnesses of the kill,” writes Elias Canetti in Crowds and Power , about the hunting pack, “may have a claim to part of the prey. When this is the case, spectators are counted as accomplices of the deed; they share the responsibility for it and partake of its fruits.” Together these men raped and hanged, and made us all watch caste at play like spectator sport.

In this case, as both metaphor and meaning, something more than pro forma promises of legal action is needed. Surely we need an equally public, consumable, spectacle of remorse and penitence? Where is the plaque under a mango tree, or under a thousand such trees, memorialising these horrors so they may never recur? Where is the leader, or a thousand leaders, saying “never again”?

For if the “new” national mantra of development and governance has no space for seeking this redemption, our moral order, weakened as it is, lies truly scattered to the winds.

(Farah Naqvi is a writer and activist working on public policy for rights of the most marginalised.)

Leave a Reply