UN- Habitat released a consolidated research report titled “The State of the Urban Youth India 2013: Employment, Livelihoods, Skills”, which brings together research findings, data and literature to suggest the need for a paradigm shift in addressing the issue of the urban young. The report developed by IRIS Knowledge Foundation and brought out by Narotam Sekhsaria Foundation (NSF), addresses the current status of youth in urban India through a focus on health, politics, governance, law, jobs, education, gender, migration, labour and other areas of opportunities in the country. Included is also a three-city survey on young people’s perception of employment opportunities.

The first ever State of the Urban Youth, India, 2013 report explores a range of issues faced by Indian youth such as issues of equality and inequality, education and employment, work, health and safety and internal migration.

- Youth Demographic Overview

ü Every third person in urban India is a youth. In less than a decade from now, India, with a median age of 29 years will be the youngest nation in the world. There are large numbers of working population between the ages of 15-59 that will be generating incomes sufficient to share the state’s burden in supporting those that cannot yet do so. India could take advantage of the ‘demographic dividend’ resulting from this demographic transition over this decade potentially contributing to

economic growth.

- Urban Youth in Health and Illness A Rights Perspective

ü The so-called older age group diseases are today appearing among younger age groups. For example cardiovascular diseases and diabetes. These and cancers are lifestyle diseases whose progressions are affected by early habits and environments of childhood. More than half the disabled in India are under 30 years. There are more young disabled in urban than rural areas. Focused research on the health concerns of youth in both urban and rural areas needs to be conducted in order to evolve appropriate well-targeted programmes.

ü Various policies recognize and identify the youth as a group with special and distinct needs that have to be met, however the biggest challenge is lack of data on the subject, making it difficult to bring out the complexities of the health characteristics of the urban youth.

ü Available data categorises the youth as a monolith, leaving behind several vulnerable groups like low-income groups, the disabled, migrants and sexual minorities. This in itself highlights the pressing need for more studies focusing on the health of the youth both spatially and temporally.

- Urban Youth and Political Participation

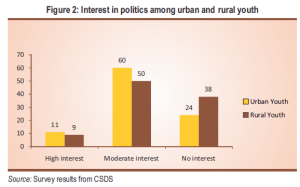

ü Anecdotal and survey evidence shows that youth interest in politics is on the rise. However, the large scale participation of urban youth in social movements at least during last few years, hardly help us understand urban youth’s level of interest and participation in politics. The interest in politics is confined to young urban men. Those who admit to significant exposure to the media show greater interest in politics. Education is a factor in young people’s rising interest in politics. Greater participation in election related activities does not translate into larger voter turnout. The urban youth is politically oriented, but still not politically very active, and a few steps away from becoming an active political community.

ü Findings of the survey conducted by Centre for the Study of Developing Society (CSDS) indicate, three-quarters of urban youth show varying degrees of interest in politics and only one-quarter have no interest in politics. There were a few who could not express their views on this issue. Though the number of urban youth who show interest in politics is sizeable (71 percent) a large proportion have only moderate interest in politics and only 11 percent have a great deal of interest in politics. There has been a marginal increase in urban youth’s interest in politics in the last couple of years. However, there is only a marginal difference between rural youth and urban youth when it comes to taking an interest in politics.

- Policy Perspectives

ü The evolution of the youth development index is imperative. This will not only enable the monitoring of various programmes and their impact, but also envisage new directions for youth involvement in development. Each state needs to develop and put into action a youth policy. This will address the state-specific challenges to youth development. Such policies are even more necessary in states with lower proportions of youth since it is here that youth issues are most neglected.

- Youth Rights, Law and Governance

ü It is believed that anti-social behaviour among children and young people has reached a historic high. Newspapers constantly highlight serious crimes by youth. Eg: Rave Party raids by police and consequences of arrests on youth, Drink and Drive Offences by youth – Alistair Pereira & Nooriya Haveliwala case, Palm Beach Road Accident, Jessica Lal murder case – influence of alcohol, power and money, Gopal Kanda- job, promotion, sexual assault, facebook post web crime case, the vicious gang-rape of a 23-year-old Delhi physical therapy student — in which a 17-year-old boy is alleged to have taken part has received global attention.

ü There is lack of awareness and a failure in implementing the laws and policies relating to youth, in letter and spirit. All policies of any Government are ultimately interrelated with one another and with the constitutional rights, duties and directives. Convergence between various legislations is necessary.

ü India’s resurgence potential as an economic and a socially responsible power rests on the Indian youth who must be aware of their rights, laws and policies and help in implementing them. They must become agents of law reform campaigns and movements for social change.

- In Search of Jobs and Education: A Three-City Youth Survey

- Urbanisation, Inequality and Youth

ü Top 10 cities contribute to 80 per cent of growth in India.

ü Sprawl and glaring inequality characterise cities in India as they do in any developing country.

ü To the mass of young people living in cities the inequality is palpable, visible everyday and affects their life choices.

ü The aspiration-reality mismatch makes for two outcomes: it may engender violence; or, it may produce an entrepreneurial flowering. The second more favourable outcome can be encouraged with the availability of resources, support and opportunities for skill development.

- Internal Migration Among Youth for Education and Employment

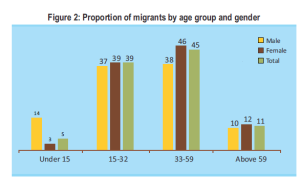

ü More than 110 million young are on the move across the country but most of them do not travel far, moving within the state.

ü Some 17 per cent of migration for education is across states

ü Unlike the case of migration for education which was primarily an intra-state

phenomenon, 45.6 percent of individuals migrate to work in other states. Moreover,

72.9 per cent of these migrant workers moved from rural areas

- ü The movement shows that there is an internal brain drain from the states with poor education and employment opportunities that in turn keeps these states from developing their potentials.

- Women in the Workforce Where are they?

ü India has an adverse sex ratio that has not shown much improvement. It is still a worrying 914 women to 1000 men. Urban sex ratios are no better.

ü As per the Planning Commission report of Working Group on Secondary and Vocational Education for Eleventh Five Year Plan, the Gross Enrolment Ratio for classes IX –XII in 2004-05 was 39.91 per cent. The figure for classes IX and X was 51.65 per cent whereas that for classes XI-XII was 27.82 per cent.

ü Instead of viewing adolescent girls only through the lens of their natal families, they should be seen as individuals in their own right, who require laws and policies for protecting and promoting their rights.

- Youth Labour Market in India Opportunities and Choices

ü In India, mostly informal jobs, with low pay and no social security, tend to emanate from industries that create more jobs for the youth while those industries offering more formal jobs are less absorptive of growing workforce.

ü Only minuscule share of jobs in India that are available to youth are formal, carrying entitlements like social security while a vast majority of opportunities for the youth are informal in nature.

ü Indian youth, men and women, are increasingly enrolling in tertiary education, throwing a big challenge for the state and society to provide them decent work options in future. For Indian youth education appears to be pivotal in getting decent job and earning a good pay.

ü Most significantly, in India, there is perceptible discrimination against young women in the

participation of labour market; a huge proportion of them engage in domestic duties. This

should be a serious policy concern.

- Education and Employment Bridging the Gap

ü There is a widening gap between skills and job market needs.

ü Hidden underemployment of educated youth is very evident.

ü Rising youth disenchantment does not augur well for the country.

Key recommendations:

• Vocational education streams need to be introduced across school boards in the country in

conjunction with industry.

• A National Vocational Education Qualifications Framework that will allow mobility of students

between traditional higher education and vocational streams needs to be introduced

• Accreditation rating of higher educational institutions, particularly schools offering professional education, to industry requirement, including the extent to which industry inputs are taken in drafting curricula. Accreditation should be mandatory for all educational institutions as soon as possible.

• The curriculum and the mandate needs to be updated, to focus on the demands of today’s industry and the reality of where jobs lie.

• A statutory body modeled on the National Knowledge Commission, needs to be set up with the mandate to regularly research and point out the challenges facing India’s push to utilize its demographic potential.

- Youth in the Informal Sector

ü More than 90 per cent of the workforce and about 50 per cent of the national products are accounted for by the informal economy.

ü Only 11.5 per cent had received (or were receiving) any training, whether formal or informal. Only a third of these had received formal training. The largest share of youth with formal skills was in Kerala (15.5 per cent), followed by Maharashtra (8.3 per cent), Tamil Nadu (7.6 per cent), Himachal (5.60 per cent) and Gujarat (4.7 per cent). Among those undergoing training Maharashtra had the highest share, Bihar the lowest

ü The six states of southern and western India, a continuous zone, accounted for 63 per cent of all formally trained people. These are also the states with more industry, higher levels of education, and training opportunities.

ü The chances of acquiring training increases disproportionately with location and minimum

education. A person in an urban area has 93 per cent greater chance of acquiring training than in the rural areas. A person with a high school degree has a 300 per cent chance of acquiring training than an illiterate person

- Work, Health and Safety

ü Reliable data on workplace health, injury and death is available only for workers in registered establishments that accounts for roughly 3 per cent of all workers. Work locations with high risks usually have the largest number of youth, especially low skilled workers.

ü Industries like cotton ginning and garment production, chemical, construction industry among the staple industries registering the quickest employment growth are also high-risk environments and are poorly regulated.

ü Relatively new occupations that attract young adults, like pizza and other food delivery — offer little protection to the worker who is pushed to higher output through persuasion and incentives resulting in high risks.

ü Food processing, scavenging and cleaning work and recycling that have a large proportions of youth are hazardous and unregulated places of work.

ü With the waning of the labour movement, workers have neither voice nor a platform where they may seek redressal. This has resulted in sporadic, spontaneous and violent worker responses to such incidents as deaths that only serve to mitigate chances of long-term reform.

- Youth in Urban Transition A Sustainability Challenge

ü Mainstreaming the agency of youth for sustainable cities calls for strategies that integrate youth concerns and experiences into a conceptual framework, design and implementation and prioritising Youth-led development at the grass-roots level.

ü Fast-tracking data efforts for the construction of composite indexes on youth development for urban and rural areas would motivate greater youth-inclusion in public policy and in India’s on-going urban transition.

- Youth Labour Market in India Opportunities and Choices

ü In India, mostly informal jobs, with low pay and no social security, tend to emanate from industries that create more jobs for the youth while those industries offering more formal jobs are less absorptive of growing workforce.

ü Only minuscule share of jobs in India that are available to youth are formal, carrying entitlements like social security while a vast majority of opportunities for the youth are informal in nature.

ü Indian youth, men and women, are increasingly enrolling in tertiary education, throwing a big challenge for the state and society to provide them decent work options in future. For Indian youth education appears to be pivotal in getting decent job and earning a good pay.

ü Most significantly, in India, there is perceptible discrimination against young women in the

participation of labour market; a huge proportion of them engage in domestic duties. This

should be a serious policy concern.

- Education and Employment Bridging the Gap

ü There is a widening gap between skills and job market needs.

ü Hidden underemployment of educated youth is very evident.

ü Rising youth disenchantment does not augur well for the country.

Key recommendations:

• Vocational education streams need to be introduced across school boards in the country in

conjunction with industry.

• A National Vocational Education Qualifications Framework that will allow mobility of students

between traditional higher education and vocational streams needs to be introduced

• Accreditation rating of higher educational institutions, particularly schools offering professional education, to industry requirement, including the extent to which industry inputs are taken in drafting curricula. Accreditation should be mandatory for all educational institutions as soon as possible.

• The curriculum and the mandate needs to be updated, to focus on the demands of today’s industry and the reality of where jobs lie.

• A statutory body modeled on the National Knowledge Commission, needs to be set up with the mandate to regularly research and point out the challenges facing India’s push to utilize its demographic potential.

- Youth in the Informal Sector

ü More than 90 per cent of the workforce and about 50 per cent of the national products are accounted for by the informal economy.

ü Only 11.5 per cent had received (or were receiving) any training, whether formal or informal. Only a third of these had received formal training. The largest share of youth with formal skills was in Kerala (15.5 per cent), followed by Maharashtra (8.3 per cent), Tamil Nadu (7.6 per cent), Himachal (5.60 per cent) and Gujarat (4.7 per cent). Among those undergoing training Maharashtra had the highest share, Bihar the lowest

ü The six states of southern and western India, a continuous zone, accounted for 63 per cent of all formally trained people. These are also the states with more industry, higher levels of education, and training opportunities.

ü The chances of acquiring training increases disproportionately with location and minimum

education. A person in an urban area has 93 per cent greater chance of acquiring training than in the rural areas. A person with a high school degree has a 300 per cent chance of acquiring training than an illiterate person

- Work, Health and Safety

ü Reliable data on workplace health, injury and death is available only for workers in registered establishments that accounts for roughly 3 per cent of all workers. Work locations with high risks usually have the largest number of youth, especially low skilled workers.

ü Industries like cotton ginning and garment production, chemical, construction industry among the staple industries registering the quickest employment growth are also high-risk environments and are poorly regulated.

ü Relatively new occupations that attract young adults, like pizza and other food delivery — offer little protection to the worker who is pushed to higher output through persuasion and incentives resulting in high risks.

ü Food processing, scavenging and cleaning work and recycling that have a large proportions of youth are hazardous and unregulated places of work.

ü With the waning of the labour movement, workers have neither voice nor a platform where they may seek redressal. This has resulted in sporadic, spontaneous and violent worker responses to such incidents as deaths that only serve to mitigate chances of long-term reform.

- Youth in Urban Transition A Sustainability Challenge

ü Mainstreaming the agency of youth for sustainable cities calls for strategies that integrate youth concerns and experiences into a conceptual framework, design and implementation and prioritising Youth-led development at the grass-roots level.

ü Fast-tracking data efforts for the construction of composite indexes on youth development for urban and rural areas would motivate greater youth-inclusion in public policy and in India’s on-going urban transition.

Conclusion:

Mainstreaming the challenges and agency of youth is an essential underpinning of the Habitat Agenda for sustainable cities.

October 21, 2013 at 12:15 pm

Excellent Article with an in depth insight in to plight of youth.