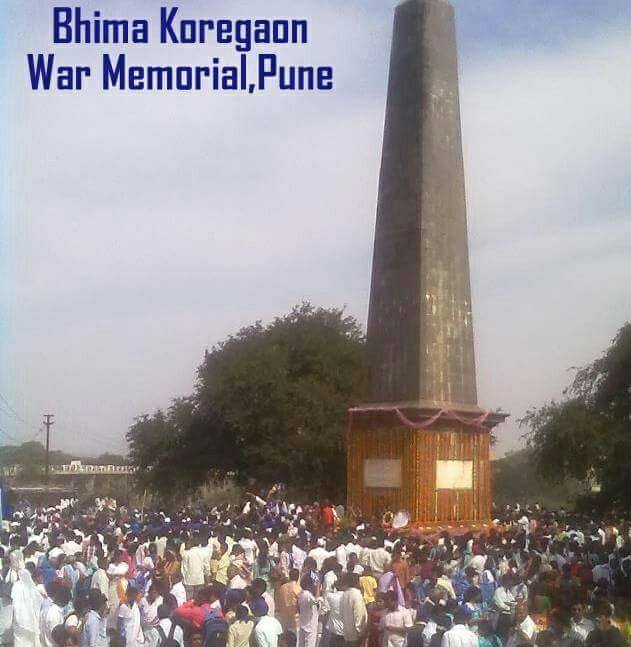

Examining continuity and change in the commemorative history of an imperial war memorial, this paper shows that the contestations for hegemony in the present often take the form of contestations about memories. The Koregaon Bheema obelisk near Pune, which was built to reconfirm the belief of the British in their own power, today serves much the same function but for a different group of people – former untouchable Mahars – who had no choice but to collaborate with the colonisers against a tyrannical native regime.

Shraddha Kumbhojkar

The British East India Company began its direct political ascendancy in eastern and northern India with the battle of Plassey in 1757. Gradually, it extended its political hold to other parts of India. During the same period, the Peshwa rulers (1707-1818) were also spreading their political influence in all directions from their base in Pune. Clashes between the Peshwas and the Company seemed inevitable. On 1 January 1818, a battalion of about 900 Company soldiers, led by F F Staunton, on a march from Seroor to Pune suddenly found itself facing a 20,000-strong army led by the Peshwa himself at the village of Koregaon1 on the banks of the river Bheema. In the words of Grant Duff, who was a contemporary official and historian, “Captain Staunton was destitute of provisions, and this detachment, already fatigued from want of rest and a long night march, now, under a burning sun, without food or water, began a struggle as trying as ever was maintained by the British in India.”2 Neither side won a decisive victory but despite heavy casualties Staunton’s troops managed to recover their guns and carry the wounded officers and men back to Seroor.

As this was one of the last battles of the Anglo-Maratha wars that soon resulted in the complete victory of the Company, the encounter quickly came to be remembered as a triumph. The East India Company wasted no time in showering recognition on its soldiers. While Staunton was promoted to the honorary post of aide-de-camp by the governor general,3 the battle received special mention in parliamentary debates the next year.4 A memorial was commissioned and Lt Col Delamin, who passed by the village the next year, witnessed the construction of a 60-foot commemorative obelisk.5

Almost two centuries later, the Koregaon memorial still stands intact. It is supposed to commemorate the British and Indian soldiers who “defended the village with so much success”6 when they confronted the Peshwa army in a “desperate engage-ment.”7 The marble plaques in English along with Marathi translations adorning the four sides of the monument declare that the obelisk commemorates the defence of Koregaon in which Captain Staunton and his corps “accomplished one of the proudest triumphs of the British army in the East.”8 Soon after, the word “Corregaum” and the obelisk were chosen to adorn the official insignia of the regiment.9

Later chroniclers of colonial rule continued to shower praise on the largely outnumbered British force for displaying “the most noble devotion and most romantic bravery under the pressure of thirst and hunger almost beyond human endurance.”10 In 1885, even the Grey River Argus, a newspaper published in far-off New Zealand, described the battle in glowing terms.11 After the turn of the century, though, the colonial commemoration began to fade and there were no significant subsequent references to the battle in British literature and public memory.

Memories: ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’

Today, the memorial stands just off a busy highway toll-collection booth. Every New Year day, the urban middle classes who use the highway remind each other to avoid the stretch that passes by the memorial with the warning that “those people will be swarming their site at Koregaon”. Indeed, the memorial has become a place of pilgrimage, attracting thousands of people every 1 January. If one stops by to ask the pilgrims what brings them there, they say, “We are here to remember that our Mahar fore-fathers fought bravely and brought down the unjust Peshwa rule. Dr [B R] Ambedkar started this pilgrimage. He asked us to fight injustice. We have come to find inspiration by remembering the brave soldiers and Dr Ambedkar.”12

One might be baffled by this admiration for the native soldiers who fought on the British side and lost their lives in a fight against their own countrymen. A scrutiny of the list of casualties inscribed on the memorial reveals that more than 20 names of the native casualties listed end with the suffix “-nac” – Essnac, Rynac, Gunnac. This suffix was used exclusively by the “un-touchables” of the Mahar caste who served as soldiers. This is particularly relevant when juxtaposed with the caste of the Peshwas who were orthodox, high-caste brahmin. This is where one realises that the story of Koregaon is not just about a straightforward struggle between a colonial power and a native one; there is another important but largely ignored dimension to it – caste.

The Peshwas were infamous for their high-caste orthodoxy and their persecution of the untouchables. Numerous sources document in detail that under the Peshwa rulers the untouchable people who were born in certain low castes received harsher punishment for the same crimes committed by those from high castes.13 They were forbidden to move about public spaces in the mornings and evenings lest their long shadows defile high-caste people on the street. Besides physical mobility, occupational and social mobility was denied to these people who formed a major part of the population. In 1855, Mukta Salave, a 15-year-old girl from the untouchable Mang caste who attended the first native school for girls in Pune wrote an animated piece about the atrocities faced by her caste.

Let that religion, where only one person is privileged and the rest are deprived, perish from the earth and let it never enter our minds to be proud of such a religion. These people drove us, the poor mangs and mahars, away from our own lands, which they occupied to build large mansions. And that was not all. They regularly used to make the mangs and mahars drink oil mixed with red lead and then buried them in the foundations of their mansions, thus wiping out generation after generation of these poor people. Under Bajirao’s rule, if any mang or mahar happened to pass in front of the gymnasium, they cut off his head and used it to play ‘bat ball’, with their swords as bats and his head as a ball, on the grounds.14

Even today, Peshwa atrocities against the low-caste people remain ingrained in public memory.15 Human sacrifice of untouchable people was not uncommon under these 17th century rulers who framed elaborate rules and mechanisms to en-sure that they remained the same as their name – untouchable. When the British East India Company began recruiting soldiers for the Bombay army, the untouchables seized the opportunity and enlisted themselves. Military service was perceived to help open the doors to economic as well as social emancipation. Political freedom and nationalism had little meaning if one had to choose between a life where the best meal on offer was a dead buffalo in the village16 and a life where some dignity was evi-dent, not to mention a decent monthly pay in cash.

The valour the untouchable soldiers who fought on the side of the British is not perceived as a shameful memory today. In fact, Koregaon has become an iconic site for the former untouchables because it serves as a reminder of the bravery and strength shown by their ancestors – the very virtues the caste system claimed they lacked. This may help to explain how a me-morial to a colonial victory built in the early 19th century has been adapted to serve as a site that inspires those who belong to castes earlier considered untouchable.

The battle of Koregaon and the memorial was mentioned in an increasingly congratulatory tone in a number of documents on military history published in Britain throughout the 19th century. In parliamentary debates in March 1819, the event was summed up as follows: “In the end, they not only secured an unmolested retreat, but they carried off their wounded!”. In a volume published in 1844, Charles McFarlane quotes from an official report to the governor that it was “one of the most brilliant affairs ever achieved by any army in which the European and Native soldiers displayed the most noble devotion and the most romantic bravery”.17 Twenty years later, H Morris confidently added, “Captain Staunton returned to Seroor, which he entered with colours flying and drums beating, after one of the most gallant actions ever fought by the English in India”.18

Mahars and the Military

However, in the 20th century, with British rule firmly established over most of India, the Koregaon memorial faded from main-stream commemorations. Neither Britain at the height of colonial glory, nor India, which was beginning to get independence in small doses, had time to commemorate a violent struggle that had taken place in the days of the East India Company.19 The valour of the Mahar regiment, however, continued to be manifested in the battles of Kathiawad (1826), Multan (1846) and the second Afghan War (1880). However, breaking their tradition of loyalty, some sepoys from the Mahar regiment, which was a part of the Bombay army, joined the Indian mutiny against the British in 1857. Subsequently, Mahars were declared a non-martial race and their recruitment was stopped in 1892.

The Mahars soon began to feel the pinch. Gopal Baba Valangkar, a retired army man, had founded a Society for Removing the Problems of Non-Aryans.20 In 1894, the members of this society wrote a petition to the governor of Bombay reminding him that the Mahars had fought for the British to acquire their present kingdom and requested a reconsideration of the decision to ex-clude Mahars from the martial races, which deprived them of entry into military service. The petition was rejected in 1896.21

Another leader of the untouchables, Shivram Janba Kamble, made even more sustained efforts to emancipate them. He had been involved in the work of the Depressed Classes Mission that ran schools for untouchable children. In October 1910,

R A Lamb of the Bombay governor’s executive council was invited as the chief guest for a prize distribution ceremony in one of these schools. In his speech, Lamb mentioned the Koregaon memorial, which he visited annually. He drew attention to the “many names of Mahars who fell wounded or dead fighting bravely side by side with Europeans and with Indians who were not outcastes” and regretted that “one avenue to honourable work had been closed to these people”. It is not known whether it was Lamb’s speech that threw the spotlight back on the Koregaon memorial or whether it was already a part of the collective memory but the speech certainly lent weight to the argument that it was Mahars who fought for the British that helped make them “masters of Poona”.22

Kamble conducted a number of meetings of Mahars at the memorial site in the first decades of the 20th century. In 1910, he organised a conference of the Deccan Mahars from 51 villages in the western region. The conference sent an appeal to the sec-retary of state demanding their “inalienable rights as British subjects from the British Government”.23 They made a strong case to let Mahars re-enter the army and argued that Mahars “are not essentially inferior to any of our Indian fellow-subjects”.24 Up until 1916, various gatherings of untouchables in western India kept repeating this request to the rulers. As the first world war gained momentum, the Bombay government in 1917 issued orders for enlistment in the army, including the formation of two platoons of Mahars.25

The Coming of Ambedkar

However, the Mahars’ happiness was short-lived – the British army stopped recruiting them as soon as the war ended and this renewed their campaign for recognition of the valour of the untouchables. It had by then assumed the shape of a movement for the general emancipation of untouchables. Within this campaign, the Koregaon memorial had become a focal point; various meetings were held at the obelisk during which Kamble and other leaders invariably reminded the untouchables of the valour and prowess exhibited by their forefathers. On the anniversary of the Battle of Koregaon on 1 January 1927, Kamble invited Ambedkar to address the gathering of Mahars.26 Ambedkar was not just another leader of the untouchables; he was by then a force to reckon with in Indian politics.

Ambedkar was born in 1891 to a retired army subedar from the Mahar caste. Despite first-hand experience of caste discrimi-nation, he obtained a doctorate from Columbia University, a DSc from the London School of Economics and was called to the bar at Gray’s Inn by the age of 32 and in 1926 became a member of the Bombay legislative assembly. He could not fail to appreci-ate the significance of the memorial for advancing the cause of emancipation of the untouchables and not only made an in-spiring speech before the gathering but also supported the idea of reviving the memory of the valour of their forefathers by vis-iting the memorial annually on the anniversary of the battle. As a representative of the untouchables, Ambedkar was invited by the British to the Round Table Conference in 1931 that was to decide on the future of India. Based on his arguments at the conference, he wrote a small treatise titled “The Untouchables and the Pax Britannica” in which he referred to the Battle of Ko-regaon to support his argument that the untouchables had been instrumental in the establishment and consolidation of British power in India.27

Indian mainstream politics from the 1920s to 1947 is recognised as the Gandhian era. M K Gandhi, born in the middle-order caste of traders, had a different outlook on the systemic exploitation of the untouchables on grounds of caste. He called the untouchables harijans, meaning people of god. Ambedkar and his followers resented both the name and the patronising atti-tude behind it. Going beyond this, there were major ideological differences between Ambedkar and Gandhi. For the India rep-resented by Gandhi and the Indian National Congress, the primary contradiction was between colonial supremacy and Indian aspirations for political freedom; for Ambedkar and the untouchable masses he represented, the oppression was not located in the political system but in the socio-economic sphere. There was a clash of interests. The Congress under Gandhi sought to rep-resent all Indians in a unified front against colonial rule; Ambedkar and the untouchables, for their part, were certain that re-placing colonial rulers with high and middle-class Congress leaders offered no solution to their problems. The known devil of colonial rulers was more tolerable to the untouchables.

In 1930, Gandhi embarked on the civil disobedience movement against the systems and institutions of the colonial rule. Kamble and a few other representatives of the depressed classes retaliated by launching what they called the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party. Its manifesto, quoted in the Bombay Chronicle, said,28

In view of the fact that Mr Gandhi, Dictator of the Indian National Congress has declared a civil disobedience movement before doing his utmost to secure temple entry for the ‘depressed’ classes and the complete removal of ‘untouchability’, it has been decided to organise the Indian National Anti-Revolutionary Party in order to persuade Gandhiji and his followers to postpone their civil disobedience agita-tion and to join whole-heartedly the Anti-Untouchability movement as it is…the root cause of India’s downfall…The Party will regard British rule as absolutely necessary until the complete removal of untouchability.

Though this party did not attract much support, it demonstrates that for the untouchables social and economic well-being was of greater, and more immediate, concern than political freedom, and hence colonial rule was deemed a necessary evil for the time being. It also shows that there were other, often contradictory voices in the independence movement that have often been glossed over in nationalist rhetoric.

A New Memory

India won its independence in 1947 and its new constitution was drafted by a committee chaired by Ambedkar. The “an-nihilation of caste”,29 however, remained a distant dream. Parliament did not accept the Hindu Code Bill proposed by Ambedkar to bring about far-reaching reforms in the Hindu sociocultural scene and a disillusioned Ambedkar resigned from the Cabinet in 1951. In 1956, millions of untouchables under his leadership converted en masse to Buddhism as a step towards at-taining total freedom from exploitation. The same year, after Ambedkar passed away in December, a political party called the Republican Party of India (RPI) was formed to represent the interests of the downtrodden.

The mass conversions opened the floodgates for cultural conflict with the high castes. The immediate reaction of the Hindu right was of denial. The strategy of cultural appropriation that has worked so well for Hinduism from the time of the Buddha is employed even today to project the Buddhists as just another sect within Hinduism.30 For the neo-Buddhists, this necessitated the creation of new and different cultural practices. Among the neo-Buddhists in western India, the pilgrimage to the Koregaon memorial emerged as one of the invented cultural practices and thousands of them throng to the memorial every New Year day to commemorate the valour of the Mahars who helped to overthrow the unjust high-caste rule of the Peshwa. They also com-memorate Ambedkar’s visit to the place on 1 January 1927.

Unlike any other site of Hindu pilgrimage, the Koregaon memorial is devoid of the telltale signs of a holy marketplace. No sellers of garlands, sweets and images of gods are found here. It is deserted all through the year; however, come New Year, and the place is dotted with little stalls selling books, cassettes and CDs. Various publishers of Ambedkarite literature put up stalls for their books; neo-Buddhist songs played loudly describe Ambedkar’s greatness and the need to change the world;31 leaders of the now numerous factions of the RPI address their followers; neo-Buddhist families visit the memorial obelisk to offer flowers or light candles.

An important part of the ritual is offering a vandana, a recital of verses from Buddhist texts. Another equally important item on the programme is to buy books. Interviews with various booksellers reveal that whenever there is a gathering or pilgrimage of neo-Buddhists, bookstalls do roaring business. The average size of books sold at these stalls is mostly small – 30 to 70 pages priced between Rs 10 and Rs 50, indicating that the readers are largely neo-literate, have very little time to spend on reading and can only afford low-priced books. Many publishers of related literature said that their daily sales figures at the Koregaon pilgrimage and other such events (for example, Mumbai and Nagpur) were often more than their sales figures for the rest of the year.32 This could be perceived as an indication of the belief in the emancipatory potential of education among neo-Buddhists, especially of the former Mahar caste. Some of the bestselling titles include Marathi translations of books authored by Ambedkar such as Buddha and His Dhamma, Annihilation of Caste and Who Were the Shudras? Other popular books include dalit autobiog-raphies besides dalit poetry and short biographies of dalit leaders.

These books offer a dalit viewpoint of Indian history in which colonial rule is seen to be instrumental for emancipation, though ignorant of the realities of caste exploitation. While Jotirao Phule and Ambedkar are among the prominent dalit writers who propounded this view, Gandhi and the movement for India’s independence do not figure positively in this paradigm. However, the fact that Ambedkar chaired the committee that wrote the Constitution of India in 1950 is considered very im-portant and any attempt to criticise or seek a change in the Indian Constitution draws opposition from the dalits. For instance, dalit leaders and their followers have refused to endorse Anna Hazare’s campaign for a Lokpal, an extra-constitutional om-budsman.

The Importance of Forgetting

Interestingly, though the Koregaon memorial was commissioned by the colonial rulers, it does not feature on the commemora-tive landscape of the British public today. This amnesia may be attributed to the fact that memories of empire, especially vio-lent battles, are no longer a matter of pride in present-day Britain. For the high castes in India, this amnesia is understandable. Poona, the capital of the Peshwas, has metamorphosed into a software and education destination called Pune. When a sample of 130 members of high-caste, neo-rich people (who have come to be nicknamed cyber coolies) was asked about the Koregaon memorial, none of them knew what it was.33 The same respondents were also against the policy of affirmative action in the private sector to include more dalits in the globalised economy.

There is also what may be called a pseudomnesia – false memories – manufactured for elite consumption. During the 1970s, Maharashtra witnessed a spate of popular (a)historical Marathi novels on the bestseller lists. Many of them dominate the histor-ical understanding and perceptions of the Marathi-speaking middle classes even today. An important novel from this genre, authored by a brahmin, describes the battle of Koregaon in passing. Mantravegla by N S Inamdar, based on the life of Baji Rao II, claims that the battle was won by the Peshwas.34 This trend of creating pseudo-memories is more pronounced today. The third battle of Panipat, which saw the rout of the Peshwa army in 1761, is commemorated at high-sounding rallies.35 Indeed, the rhet-oric used during these rallies could lead one to believe it was the Peshwa who won at Panipat.

The Koregaon memorial occupies a very significant place in today’s neo-Buddhist culture with the internet and other elec-tronic media used to document and commemorate the Battle of Koregaon and Ambedkar’s visit. An image search for the Ko-regaon pillar yields hundreds of digital pictures; film clips of the pilgrimage are available on YouTube; at

least a dozen blogs in English and Marathi have entries related to the Koregaon memorial. They describe the battle and the role of the Mahar soldiers and also remind readers about what the untouchables could achieve when they showed resolve.

To conclude, conflicting memories have been created around the Koregaon Bheema obelisk and represent the divergent in-terests of the groups involved in their creation. Those wishing to commemorate the greatness of Peshwa rule – a symbol of high-caste supremacy – either choose to ignore the Battle of Koregaon or create the pseudomnesia of a Peshwa victory. It is also an imperial site of memory that has been largely forgotten in Britain. However, the monument has undergone a metamorphosis of commemoration, as it no longer reminds the public of imperial power, except for the former untouchables whose forefathers shed their blood at Koregaon. It serves the purpose of providing “historical evidence” of

the ability of the untouchables to overthrow high-caste oppression. Considering that Indian society is still dominated by

a system of caste hierarchy,36 the Koregaon memorial also reminds us that present-day contestation for hegemony is often manifested in contesting memories.

Notes

1 Variously spelt as Corigaum, Corregaum, Korygaom or Corygawm in contemporary English records; T C Hansard (1819), The Parliamentary Debates from the Year 1803 to the Present Time, Vol 39, p 887, House of Commons, 4 March; Carnaticus (1820), Summary of the Mahratta and Pindarree Campaign during 1817, 1818, and 1819.

2 James Grant Duff (1826), A History of the Mahrattas, Vol 3, p 434.

3 Charles Mac Farlane (1844), Our Indian Empire Its History and Present State, from the Earliest Settlement of the British in Hindoostan to the Close of the Year 1843, Vol 2, London, p 233.

4 Hansard (1819).

5 Lt Col Delamin (1831), Asiatic Journal and Monthly Miscellany, Vol 5, p 135, W H Allen & Co.

6 Delamin (1831).

7 George Newenham Wright (1835), A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency, Vol 2.

8 Inscription on the memorial obelisk, Koregaon Bheema (1822).

9 2nd Battalion of the 1st Regiment of the Bombay Native Light Infantry that eventually came to be known as the Mahar Regiment.

10 Mac Farlane (1844).

11 Grey River Argus, Vol 31, Issue 5202, 28 May 1885, p 2.

12 Interview with Shankar Munoli, a 36-year-old schoolteacher who was with a group of 60 teenagers visiting the memorial on 1 January 2010.

13 H G Frank (1900), Panchayats under the Peshwas, Poona, p 40.

14 Mukta Salave (1991), (trans Maya Pandit) “Tharu Susie, Ke Lalita”, Women Writing in India, The Feminist Press, New York, p 214.

15 For example, see G P Deshpande (2002), Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule, Leftword Books; Ambedkar, B R Annihilation of Caste at http://

ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/mmt/ambedkar/web/index.html; Rosalind O’Hanlon (2002), Caste, Conflict and Ideology, Cambridge University Press. Vijay Tendulkar’s Ghashiram Kotwal is a popular and controversial play that has been running on and off since 1972 and depicts caste-based exploitation, the downfall of the Peshwas and the ensuing power struggle.

16 A number of autobiographies in Marathi by untouchables describe the occasional “feast”

of dead buffalo meat. For example, Taraal Antaraal by Kharat Shankarrao and Baluta by Daya Pawar. Also see Dangle Arjun (ed) (1992), Poisoned Bread (Mumbai: Orient Longman).

17 Mac Farlane (1844), p 233.

18 Henry Morris (1864), The History of India, Fifth Edition, Madras School Book Society, Madras, p 207.

19 Various reforms and acts, especially Lord Ripon’s Resolution on Local Self-government in 1882 eventually led to self-government in a very limited sense.

20 The original Marathi name was Anarya Dosha Pariharak Mandali.

21 The English petition and the government resolution to make no change in the recruitment policy are quoted in C B Khairmode (1987), Dr Bheemrao Ramji Ambedkar, Vol VIII, Sugawa Prakashan, Pune, pp 228-50.

22 Text of the petition to the secretary of state quoted in H N Navalkar (1997), The Life of Shivram Janba Kamble (first published 1930), Sugawa Prakashan, Pune, p 149.

23 Navalkar 1997, p 154.

24 Navalkar 1997, p 153.

25 Khairmode 1987, p 251.

26 Anupama Rao (2009), The Caste Question: Dalits and the Politics of Modern India, University of California Press, p 346.

27 B R Ambedkar, The Untouchables and Pax Britannica, at www.ambedkar.org, accessed on 19 August 2011.

28 The Bombay Chronicle, 2 April 1930, emphasis mine.

29 This is the title of a book by Ambedkar published in 1936. Available at www. ambedkar.org

30 For example, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh on its website quotes from S Radhakrishnan’s Indian Philosophy, “Buddhism Is an Offshoot of Hinduism”. See www.sanghparivar.org

31 A popular song by an Ambedkarite poet Vaman Kardak goes “Bheemrao (Ambedkar) has passed on the message to me, Strike the anvil and change the world.”

32 Interviews with Vilas Wagh and Narayan Bhosle, publishers of Ambedkarite literature, conducted in January 2010.

33 Interviews with about 120 people from the software industry conducted in Pune, May-June 2011.

34 N S Inamdar (1969), Mantravegla, Continental Prakashan, Pune, p 17, p 461.

35 For example, see this text message received by the writer on 1 Dec 2011. “3rd January to 28 January 2012, a March towards Panipat on two-wheelers! 8 states, 76 districts, many forts, ancient temples and caves and holy places included. 7,000 kms of travel on bikes. The March begins from the historical palace of Shrimant Sirdar Satyen-draraje Dabhade Sirkar. Come one, Come all! Bring your friends along and join the Maratha forces. Yours Obediently, Prof Pramod Borhade.”

36 Shraddha Kumbhojkar and Devendra Ingale, “Wither Homo-hierarchus?”, a paper presented at the Spalding Symposium on Indian Religions, University of Oxford, March 2008. One of the findings was that caste is the deciding factor when choosing a life partner and deciding on the location of a house but not so much in the choice of friends and employers.

January 4, 2018 at 4:40 pm

The victory of dalit Mahar regiment is one of the greatest victory. The peshwa rule inflicted untold miseries on dalits. Hence their protests can be justified