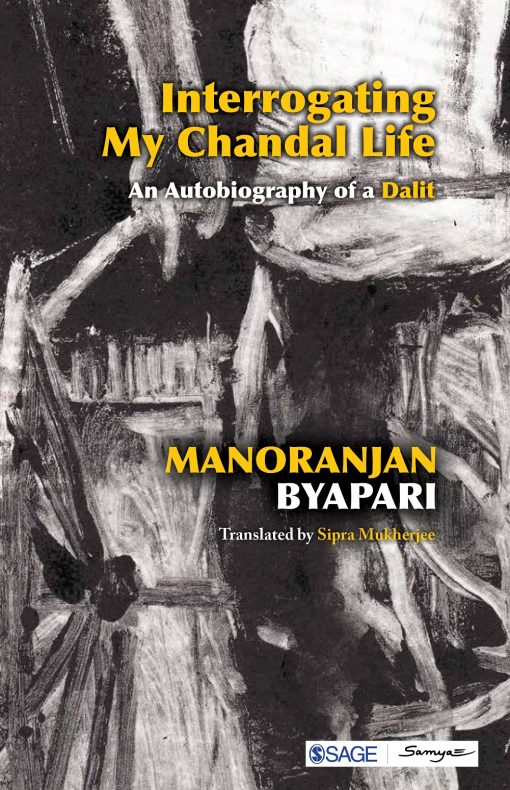

Manoranjan Byapari

“If you insist that you do not know me, let me explain myself …you will feel, why, yes, I do know this person. I’ve seen this man.” With these words, Manoranjan Byapari points to the inescapable roles all of us play in an unequal society. Interrogating My Chandal Life: An Autobiography of a Dalit is the translation of his remarkable memoir Itibritte Chandal Jivan. Translated by Sipra Mukherjee, the book talks about Byapari’s traumatic life as a child in the refugee camps of West Bengal and Dandakaranya, his involvement with the Naxalite movement, getting educated in a prison and more. The following is an excerpt from the book.

Here I am. I know I am not entirely unfamiliar to you. You’ve seen me a hundred times in a hundred ways. Yet if you insist that you do not recognize me, let me explain myself in a little greater detail, so you will not feel that way anymore. When the darkness of unfamiliarity lifts, you will feel, why, yes, I do know this person. I’ve seen this man.

Human memory is rather weak. So I would not press you to remember the forgotten days. But take a look at that green field outside your window. You will see a bare-bodied goatherd running behind his cows and goats with a stick. You’ve seen this boy many times. And so the face seems familiar to you. That is me. That is my childhood.

Now come outside your house for a while. Look at that tea stall that stands at the corner of the road where your lane meets the main road. That boy whom you see, uncombed hair, wearing a dirty, smelly, torn vest, with open sores on his hands and feet; he has been beaten a while ago by the owner of the stall for breaking a glass and has been crying—that there is my boyhood.

And then my youth. Ferrying goods at the railway station, climbing up the bamboo scaffolding to the roofs of the second or third floor with a load of bricks on my head, driving the rickshaw, waking nights as a guard, the khalasi on a long-distance truck, the sweeper on the railway platform, the dom at the funeral pyres. That is how I have spent my youth. At one stage or the other of this varied life, you must have seen me somewhere, on the road or the bazar. Or, one can never say, you may also have seen me in those tumultuous days of the seventies’ decade, running through the lanes with a bomb or a pipe-gun in my hand. Or in handcuffs being forced into the police van with blows.

Life appears to have spread skittish mustard seeds under my feet. I have never been able to stand still in any role for more than a few days, always skidding onto another spot. It is the story of that skidding, slipping, fallen-back life that I have sat down to write for you. Life has made me do so many things throughout my life, I wonder if I will be able to speak of it all even if I want to. This is a great difficulty with autobiographies—that there is no veil that I can draw around me. A novel allows that veil. And so much can be spoken outright easily. The other problem of authoring an autobiography is that one has to beat one’s own drum. Every individual is beautiful in his or her own eyes. Every individual is admirable in his or her own judgement. But to your ears, the sound of my cracked, splintered and pitted drum may sound a rhythm that irritates you because you belong to this time and society of which I am about to draw a picture. Who knows but my accusing finger may at some stage point towards you?

Somebody somewhere had once said that life was a journey. Moving from birth towards death, a step at a time. And we stumble over the rocks and stones of life, hurting and wounding ourselves, lacerating ourselves and bleeding, as we search for that eternal nectar of life—that which enriches life. Makes it great, gives it meaning.

Not all find this nectar. Some do. And the births, deaths, lives of those who do are rendered worth the while. If you do not think me vain, I will humbly submit that I have felt the touch of this nectar. So it will not be arrogant to claim that my life, even if it may not be considered supremely successful, may not be considered a failure. Though I admit I have no clear idea about what constitutes either success or failure. By birth I belong to a family that has been declared criminal, impure and untouchable. My life began with taking the goats out to graze, and then, to bring in the two mouthfuls of rice every day, in so many lowly, mean and horrible occupations. I did not get an opportunity to get to school but did get quite a few to go visit the prisons. So when people set me upon the dais, garland me and show respect, then this man, whom some tried to sweep off as dross, may perhaps reasonably feel that his life has not been a total waste. He has never crossed the threshold of school. He used to drive the rickshaw in front of Jadavpur University. When he learns that the Comparative Literature Department of that university in its volume number 46/2008– 2009, and pages numbering 125 to 137, in all those 12 pages has discussed his life and his literature—then he may justifiably feel himself blessed. When the powerful pens of many famous writers, critics, write about the literature that he has created in famous journals and newspapers—Jugantar, Bartaman, Anandabazar Patrika, Pratidin, Aajkal, The Hindu, EPW, Kathadesh, Natun Khobor, Dinkal—publishing his name and his life’s details—when popular television shows like Doordarshan’s ‘Khash Khobor’, Akash Bangla’s ‘Sadharon Ashadharon’, ‘Khojkhobor’, or ‘Tarar Nazar’ on Tara News talk about him, then his belief that life has been fulfilling may be understandable.

Once on an invitation I journeyed to the University of Hyderabad. I boarded an autorickshaw from the station, bound for the University Guest House. The driver of the auto was educated and well-informed. Upon hearing that I was from Calcutta, he wanted to know if I had heard of this writer from my city who drives a rickshaw, has never been to school, but who writes books. Did I know him? ‘Yes, I did,’ I replied. And there is not an iota of falsehood in my claim that nobody knows him better than I do. I know him even better than Alkadidi who has written about him in her novel Kalikatha: Via Bypass (1998). Or the scholars who invite me to their many universities. I know all these Manoranjans. They are all within me.

[…]

Translator’s Note:

A careful calculation brought home to me the stunned realization that, less than a kilometre from where we used to sit at Jadavpur University, a man had been led towards his ‘execution’ by an ‘army’ that wielded power to strike terror in the hearts of hardened militant Naxalites—a Jadavpur that we had no inkling of. At a tea stall there, the owner lit his coal stove, heated the pan, washed out the glasses, and handed out the tea with his right hand while with his left, he turned over the .303 bullets that had been put out to dry beside the stove. It was all routine work to him.

It is not that the violence that ran rife in these areas in the 1970s is not known, but the violence has never been narrated from this perspective. Scattered and chilling bits of information that slipped through adult conversations: of police vans stealing up to a house in the dead of the night, tipped off about the wanted in hiding there, the sound of loud bangs on the main door signalling that the police had arrived to pick up our young tenant yet again, or the sight of a young man rushing down the street and vaulting over the boundary wall of the house at the far end of the road, or of finding bombs wrapped in a plastic wrapper hidden inside our water tank, or the incoherent report given years later by the film star Uttam Kumar of witnessing the killing of a popular leader when out on his morning walk—all these were incidents we had grown up with as children of the 1970s’ Calcutta. But these were stories of the movement as seen through the upper-caste, middleclass lens. The terror, the brutality, the violence, had not been any less in these experiences, but the lenses had been different and the lanes somewhat familiar. I needed to translate Manoranjan Byapari’s autobiography because it was the other half of the story that I had not known existed.

[…]

There was one place whose name I was familiar with in this city, Jadavpur. My father would come here to look for work. I landed up there one day with the hope that if my father could find work here, I would too. The first night I spent on the railway platform No. 1, where the Ganashakti newspaper was plastered on the wall, amidst the cigarette butts and dirt.1 I had high fever that night. Painful, burning sores and welts had erupted all over my body as a result of the doctor’s reckless beating. The next morning the fever was gone, though the pain remained, and I was enormously hungry. So I went in search of work which I found in a Hindustani tea-shop. The monthly salary would be ten rupees. The bitter experience at the doctor’s house was still fresh in my mind and I changed my surname so people would not know me as a Namashudra. That identity could make it difficult for me to get a job or, if I did get a job, would get me disdainful and contemptuous treatment. The shopowner was from Uttar Pradesh, a province where they were usually very keen on the caste identity. Luck was on my side for the owner did not display any overt curiosity about my caste. I remained here for about four to five months. The monthly salary would be given on request without any hankypanky at the end of every month. But if I broke a glass they would deduct the cost of that glass from the salary. This was to teach the boys to be more careful but try as I might, I ended up breaking one or two glasses often. One day I dropped about four quarts of milk. I did not get any salary that month.

One morning, on the road in front of the shop, there was this long line of people with bamboos and tiles moving towards the east. Where on earth are they going? They were going towards the area upon which has now come up the Eastern Metropolitan Bypass. There, on the huge tracts of land lying empty but owned by the zamindars, they were going to build a colony. This would be another forcible seizure of land and the politician leading this project was a Congress minister named Ahin Ray Chowdhury. With him was another person called Shonaiya, who was later to gain notoriety as One-Handed Shona. These marching lines continued for about eight to ten days. I went to see the new colony one afternoon. As far as eye could see, there were small huts which had been built. Some of hogla leaves, some of bamboo, the lines of huts stretched endlessly. Seemingly countless, there were possibly about twenty to twenty-five thousand families there. I too wished I could take up a plot of land and make a house there. We too did not have proper place to live in. But my desires were too big for my small body and besides, were would I get the money needed to buy the bamboo or hogla.

The story goes that a man woke up late one day and so missed his train. He spent the morning dejected since this would cause him huge losses. Yet when a few hours later, news arrived of the accident that that train had met with, the man was thrilled that he had missed the train. A few days later, we were woken by cries for help from a thousand voices. The eastern sky was lit up with huge, leaping, red flames. Then came the sound of bullets being fired, repeatedly. This continued throughout the night. In the morning, along the same path traversed by those lines of people yesterday, they returned on pushcarts and makeshift stretchers. Blood dripped onto the dusty road from their bodies, evidence of the night-long hell that the police and the zamindars’ hired goons had unleashed upon them. My young mind had then been much upset at the sight of so many bloodied people and the world had not appeared a place fit for civilized humanity. It had appeared to be the domain of a tribe of murderers. But this claustrophobic arena is my country. This arena where the murderer exults is my country.

Many years ago, when my father had been beaten by the police, I had identified the police as my enemy. To that enemy was now added another, the zamindar. The police, the criminals and the zamindars I identified as the enemies of the people. My experience at the hands of the upper-caste doctor’s family had not been forgotten either. My mind was filled with anger, resentment and hatred. And wafting down on these three muddied streams as they flowed towards their turbulent meeting was my little mind, poisoned and stacked with bitter and angry experiences.

1. Translated by the translator.

The post first appeared at http://indianculturalforum.in/

November 22, 2018 at 7:25 pm

The experience of the writer indicates his sufferings due to his birth and the caste discrimination