Mihoko Takata

Mihoko TakataSome of the details described below may be upsetting.

I worked for the UK Border Agency (UKBA) for 10 years, three of which were spent reviewing asylum applications.

It was my job to review the cases of people coming to Britain in fear of their lives, and work out whether they were telling the truth or not.

There are plenty of reasons why people lie about seeking asylum. They might be trying to make a better living for themselves, or simply trying to join their family. They think they won’t get in on an immigration visa, or they can’t afford to pay for one – so they try to convince us that they need protection from persecution.

It was my job to differentiate between them, and those whose lives depended on me believing them.

Some of the stories I heard have been impossible to forget.

There was one lady who had been caught up in the Russian-Chechen war in the 2000s. She’d been taken prisoner and was raped repeatedly for 18 months. She told me she’d had several abortions, carried out by the other women in her cell.

When I questioned how an abortion could be performed in a cell, she told me, “You take one of the bedsprings from the mattress, and you use that.”

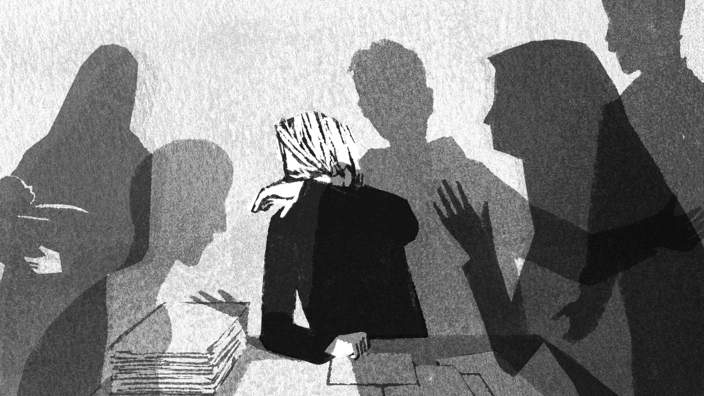

For so many of these cases, you sit someone down in a room and essentially say, “Tell me about the worst thing that ever happened to you, in detail, and I will try to prove that you are lying.”

This lady had to sit there in that room as two men, the interpreter and I, spent four hours asking her the most appalling, intimate questions, trying to disprove her story.

By the time we’d finished, I felt absolutely wretched.

However, there are some stories that stick in the mind for other reasons.

Under the European Convention of Human Rights, you cannot send anyone back to their own country if they might face the death penalty. So, when a known terrorist came to us from India, we didn’t grant him asylum, but we couldn’t send him back, either.

He’s now a taxi driver living somewhere in England.

For three years, I made judgements on cases like these, interviewing maybe five or six people per week. There are people who are living in the UK today because I spent a few hours in a room with them and supported their case.

Equally, I’m sure there are people who have been wrongly sent back because of me, and God alone knows what’s happened to them. The responsibility can feel truly overwhelming.

I always tried to keep in mind what it would take to uproot your whole life, leaving your home and your country, leaving everyone and everything you know, and travelling halfway across the globe to a strange place. What would really make you do that?

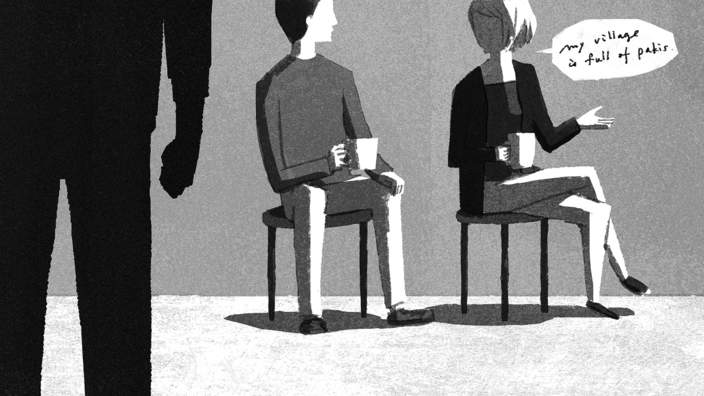

Some of my co-workers, however, seemed to think that their job was to refuse people wherever possible. I remember one caseworker complaining that her village was now, “full of Pakis”. When I asked her if she thought she was in the right job, she replied, “Yes, because I’ve got the chance to stop more coming in.” I found that incredibly disturbing.

In some cases, I was instructed to refuse a person because they didn’t meet the rules. I would go home and think, “Have I just started the process of sending someone home to die?”

There were nights where I couldn’t sleep.

Eventually, I moved off asylum interviews and started work on what we called the ‘backlog’: people who had applied for indefinite leave to remain(which would give them the right to stay in the UK without time restrictions), and whose cases had fallen through the cracks.

Some applicants had been waiting for a response for nine or 10 years. Many had already left the country, or died.

Consequently, we were under a lot of pressure to get these sorted as quickly as possible, and I felt like my ability to make sound judgements was compromised.

When you’ve not got the correct information to hand, you’re meant to write to the applicant and clarify it. But when an application is 10 years old, the chances of the person still living at the given address is slim. So we’d write to them, they wouldn’t respond, and because we couldn’t track down the necessary information, they’d be refused.

They’d still have the right to appeal that decision. But they’d often run out of time, and be forced to go home before they had a chance to do so.

I left UKBA in 2011, when the rate to apply for indefinite leave to remain in the UK was £950. Today, people pay up to £1875.

I recently spoke to someone who fled here from Zimbabwe, and is waiting for a response to his application for indefinite leave to remain. While it’s considered, he’s not permitted to work or to claim benefits. His passport is with the Government while they review his application, and will have been stamped with, “no access to public funds” – so he’s living on credit cards and handouts from friends.

His story isn’t unusual.

Because you’re without your passport while your application is considered, this often means you cannot travel. This is usually decided on a case-by-case basis. I met a woman whose mother was severely ill, but she couldn’t go home to visit her, due to her documents being with the Home Office.

I spent 10 years doing this job. The number of times I’d sat in a room and had someone tell me either the most horrendous thing imaginable, or blatantly lie though their teeth, is countless. You get to a point where you think, “actually, I can’t do this anymore”.

I now work for a charity, where I help people get themselves out of debt. I’ve never looked back.

– James, UKBA employee 2001 – 2011

A Home Office spokesperson said:

“The UK Border Agency was disbanded and restructured in 2013 to improve performance and we are now consistently meeting service standards. Our officers’ commitment to fairness when dealing with asylum claims has also been noted by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration.”

As told to Catriona White

Illustrations by Mihoko Takata

http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcthree/item/00c38bce-6163-42fa-b7b3-a3f7fce21834?

January 19, 2017 at 12:48 pm

These are horror stories and one can imagine the sufferings of the people . Those who were witness to the atrocities are bound to have sleepless nights as the ncidents haunt them for years. The violation of human rights is condemnable.