The speakers – Bela Bhatia, Soni Sori, Manish Kunjam and Isha Khandelwal – have all been denounced as “safedposh Naxali” (white-collar Naxalites) by IG Bastar SRP Kalluri, a man who flaunts his contempt for anyone who stands in the way of his mission to “drive Naxals and their dogs out of Bastar”. The picture they painted is that of a war zone – a place where ordinary citizens live in terror of being picked up and “disappeared”, or thrown into jail on vague and unspecified charges; where search and combing operations are occasions for pillaging, looting and brutal sexual violence against women and girls; where cold-blooded killings of unarmed villagers are re-packaged as “encounters”. Few of these crimes come to light; those that do are easily dismissed as aberrations, even as medals and promotions are handed out to the perpetrators. Those who raise their voices against this reign of terror and seek to bring the perpetrators to justice are targeted by vigilante groups that operate with the support and encouragement of the police, and claim to be acting in the national interest.

Kalluri’s list of “safedposh Naxali” reads like a roll call of honour. Researchers and academics like Bela Bhatia and Nandini Sundar; Adivasi leaders like Soni Sori and Manish Kunjam; lawyers like Shalini Gera and Isha Khandelwal of the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group and Balla Ravindranath and his colleagues from the Telengana Democratic Forum; media professionals Malini Subramaniam of Scroll and Alok Putul of BBC; local reporters Sumaru Nag and Santosh Yadav; hundreds of Adivasi women and men who have been variously targeted with threats, slander, false cases, illegal arrests and murderous attacks by Kalluri and his acolytes in and out of uniform.

But holes are beginning to appear in the cloak of invisibility that the state has thrown around Bastar.

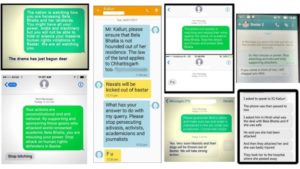

Investigations by the National Human Rights Commission have prima facie confirmed the charges of rape, sexual violence and physical assault against Adivasi women in the remote villages of Peddagellur, Bellam Nendra and Kunna. A CBI report has validated the charges brought by Nandini Sundar in the Tadmetla atrocity, holding police under Kalluri’s command responsible for unprovoked firing and torching of an entire Adivasi village. Investigations into supposed “encounters” and “surrenders” by human rights groups are more and more difficult for the state to dismiss as irrelevant in the larger scheme of things; senior officials are now forced to admit that the numbers don’t add up. The nexus between the police and goon squads is no longer a matter of speculation, thanks to trigger-happy officers in the police and district administration who compete with each other in smart-aleck repartee on social media.

There are some hopeful signs, but the tide is a long way from turning. News arrived yesterday that IG Kalluri has been asked to go on long leave. Bastar police has a new leader, but this in itself is no guarantee of change. The rhetoric of Maoist terror as a threat to the nation, to be eliminated by any means and at all costs, has paid rich dividends, both literally and metaphorically. War against the Maoists provides the perfect cover for the exploitation of Adivasi lands and forests, which are now defined not as part of India’s heritage of natural resources, but as sources of profits for mining companies, businessmen and contractors. In the general mayhem, sly actions like the suspension by the state government of key provisions of the Forest Rights Act to facilitate the handing over of forest lands to mining companies go largely unnoticed by the public.

In this version of “sabka vikaas”, the enemies are those who point out that militarised approaches to the Maoist insurgency have not only failed to stem the violence, but have also provided a cloak of impunity for gross violations of human rights by state actors.

Soni Sori, Manish Kunjam, Bela Bhatia, the JagLAG lawyers, local journalists and many others for whom Bastar is both janmabhoomi and karmabhoomi are under no illusion that Kalluri’s departure will change this larger discourse. They have no intention of giving up their struggle, or of remaining silent. But what of those who hear their stories? What of our national institutions, our Supreme Court, our human rights bodies? What of our civil servants, our public intellectuals? Our political parties, our parliamentarians, our citizens?

The packed house at the Constitution Club had no answer to Soni Sori’s question. “Again and again, we tell all of you about what is happening in Bastar, how our lives are being destroyed by this war,” she said. “You tell us to have faith in the NHRC, the Supreme Court, the Constitution. But when I go back, the women ask me – Didi, why are the men who raped us still roaming free? When will they be arrested? What are people in Delhi doing?”

February 6, 2017 at 9:37 am

The activists in the country should see that the conditions in bastar must improve . The government must be pressurised to improve the conditions of people and atrocities against women stopped so that they live comfortably