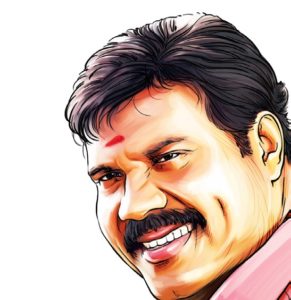

The life and work of Kalabhavan Mani, the Malayalam actor who passed away recently, reminds us how film narratives are far too bound by upper-caste, middle-class desires, dreams and biases.

How does one describe a rare phenomenon in Indian cinema like Kalabhavan Mani, who passed away recently? Very seldom has a Dalit film actor-singer like him commanded such popularity and a large fan following anywhere else. His unfortunate death at the age of 45 marks the exit of a great actor, singer and performer who couldn’t find his place in a casteist cinema world like ours. Why did a brilliant, multitalented actor like Mani not get his rightful due in Malayalam cinema, which is otherwise known for its social outlook and thematic diversity? This question has dark ramifications in post-Rohith Vemula India, where Dalit excellence and agency are systematically denied even acknowledgement, let alone recognition.

Kalabhavan Mani’s career was very short and spanned only two decades, yet his presence as an actor and, more popularly, as a singer, was indomitable and inimitable. In his first major film appearance (Sallapam/1995), Mani plays a toddy tapper who taunts and harasses the heroine by singing suggestive songs. One scene depicts a gathering of the village heads discussing the music programme planned for the upcoming festival. One elder is particularly sarcastic: “Should a toddy tapper sing? Can you imagine how good it will sound?”

Looking back, that comment sounds prophetic as the loud and clear articulation of the Malayalam film industry’s mindset. During the heydays of Mani’s career, there were reports that major actresses in the industry were not ready to act opposite him as his heroine. Yet, Mani defied everyone’s expectations and derision to win a space for himself in cinema and music, and went on to act in more than 200 films in Malayalam, Telugu and Tamil.

Coming from a very poor working class family, Mani was discovered and moulded by the famed Kalabhavan troupe of mimicry artistes. He was popular as a mimic even before he entered the world of films. Naturally bestowed with a dark-skinned body, he was destined to play the roles of the inconsequential sidekick, and—later on—the villain. Almost all the roles he did during his first decade in “Mollywood” were those of abnormal or sub-human characters—mentally challenged, drunks, sorcerers, half-wits, blind, insane. He even had to act as a bear! But, to each role he brought a certain untamed energy and explosive power, an excess that transgressed limits, which immediately struck a chord with the viewers. No wonder he was readily welcomed into the world of Tamil and Telugu films to enact the roles of villains.

What added to Kalabhavan Mani’s on-screen persona was his off-screen presence as a singer and performer. Through song and mimicry programmes performed all over Kerala, he was already hugely popular among the masses. His skills were honed by a direct communion with the jeering and cheering audiences, whose attention he had to hold as a performer through instinctive improvisation. This deep and long-lasting bonding with the audience helped him complement his film performances. Despite such talent, it was only for a brief period—between 1998 and 2007—that he had the opportunity to play some significant roles in films.

The most prominent among them were Karumadikkuttan, Valkannadi, Akasathile Paravakal, and The Guard. Outstanding was the role of a blind man in Vinayan’s Vasanthiyum Lakshmiyum Pinne Njanum (1999), which won him state and national awards for acting.

It is not a coincidence that Mani entered the film scene in the mid-1990s—the post-Mandal era when Dalit politics was gaining new visibility and voice in the public sphere of Kerala. Dalit consciousness was gathering storm through writings, and various land struggles and Adivasi resistance. All of that provided the wider social setting to the presence of Mani’s body and voice in the Malayalam entertainment industry. But the horizons of Malayalam film narratives and social imagination were far too bound by upper-caste, middle-class desires, dreams and biases, which denied Mani’s body its basic humanity, leave alone positive representations. In that narrative world, his body could never represent the norm/al: it was invariably placed against the norm/alcy of fair, upper-caste bodies, and so, it necessarily had to be mean, excessive, perverse, divergent or dangerous. Kalabhavan Mani’s life and work once again prove that a dark-skinned body can never be “realised” or expressed by, and within, Indian cinematic imagination, raising disturbing questions about the place and agency of a dark, Dalit body in Indian film narratives.

Interestingly, the brief interregnum when Mani wielded star power lies between the fag end of the superstar era and the emergence of the “New Gen” movies in Malayalam cinema. The tragedy was that he was caught between the two: he was too intense, sharp and tall to play the self-abusing sidekick roles to superstars, and for the new-generation cinema of the youth, rooted and indigenous actors like him had no significant space within its fake-urban, middle-class imagination. So, during the last years of his life, he found himself more at home in his natural terrain where he had no equals: singing folk songs and performing stage shows.

Kalabhavan Mani will most probably be remembered more for his songs than for his film roles. For one, neither his presence as an actor, nor the roles he played, suited small-screen television viewing (the afterlife of cinema); he was more of a big-screen, theatre actor.

But as a singer, he was easily able to reach out to the masses, giving a new life to folk songs and public singing in Kerala. Starting with folk songs from his own local milieu, he expanded his repertoire to include songs about individual sorrows and dreams, the hugely popular bhakti songs on Lord Ayyappa, and “Mappila” (Malabar, North Kerala Muslim) songs. ‘

Kalabhavan Mani’s voice crossed the boundaries of caste and class; after all, “unhearability” is not as strong as “untouchability.” Mani’s voice reaches your ears in spite of you. You won’t—nay, you can’t—will it, but you have to open your eyes to see.

C S Venkiteswaran ([email protected]) is a film critic and commentator based in Thiruvananthapuram

- See more at: http://www.epw.in/journal/2016/18/postscript/dalit-body-brahminical-world.html#sthash.t94neEQT.dpuf

May 2, 2016 at 4:10 pm

Mani did not act as the bear. Kalabhavan Shajon did that part. You missed a huge part of his first gen; his brilliant comedy in movies such as Summer in Bethlehem.