In 1927, an iconic struggle of the Dalits in Mahad, in modern day Maharashtra, had to take a step back in spite of overwhelming enthusiasm of the community. Nearly nine decades later, in Pathapally in India’s youngest state, Telangana, a more than three-month-long struggle of the Madigas, a Dalit community, forced the administration to accept its demands. This article traces the events and developments of the Pathapally movement and compares it with its iconic predecessor.

The Pathapally Dalit Baditha Nyaya Porata Samiti (PDBNPS), a united front of 11 organisations created to spearhead the struggle of the Dalits of Pathapally village, decided to observe 25th anniversary of the Tsundur Massacre1 on 6 August. It also decided to undertake a long march from Pebber to Pathapally to press its demands which the administration had ignored despite a series of protests by the organisation—including a relay fast from 8 July near the Ambedkar statue, not very far from the Pebber Mandal Office—for more than two months.

A day before the march, the administration declared it would impose Section 144 on the stretch beginning from the Pebber exit on the Hyderabad–Bengaluru highway, and ban entry to Pathapally village on 6 August. But in an exemplary display of defiance, nearly 7,000 Dalits from surrounding villages gathered in solidarity with the Pathapally Dalits and forced the administration to give in to their demands. The administration was also compelled to give a commitment to honour its promises.

The Pathapally struggle is the first Dalit struggle after the formation of the Telangana state. It is testimony to the fact that even Telangana, with its legacy of radical movements stretching back to pre-independence times, is not immune to caste atrocities. The importance of the village’s struggle is, however, not confined to Telangana. The Pathapally struggle could well be considered Mahad of the 21st century. It could herald the advent of a new genre of Dalit movement.

The Trigger

Pathapally, a small village in Pebber Mandal in Mahabubnagar District of India’s youngest state, Telangana—a product of a popular movement that claimed the lives of more than 600 youth—is less than 15 km away from the Hyderabad–Bengaluru expressway. This expressway connects two cities that epitomise India’s high-end modernity. But it also takes one at least 100 years back when Dalits were not allowed to enter temples, use common water sources and were compelled to meekly obey the dictates of dominating castes. Those who wonder why Dalits had endured oppression for over two millennia might find their answer in Pathapally. The Dalits of Pathapally have suffered brute domination by the area’s dominant caste, Boyas, for long. Viewed this way, the struggle they waged against oppression since 1 May signifies new awakening. It gets Pathapally close to Mahad, where, nearly nine decades ago, Dalits had waged an epic struggle for a very similar purpose.

The trigger for Mahad was the passing of the Bole resolution2 in the Legislative Council of Bombay and its adoption by the Mahad municipality which opened all public water tanks for Dalits. Dalits of Pathapally did not have to wait for any such resolution—the Constitution of the country granted them these rights way back in 1950 and in addition brought in stringent laws against upper castes discriminating against or perpetrating atrocities on them.

The trigger for Pathapally came on May Day when a Madiga3 (Dalit) boy, Raghuram, a bus conductor in the Telangana State Road Transport Corporation—one of the three lucky Dalits from 40 odd families in the village to have some sort of regular employment—expressed an innocuous desire to the local Member of Legislative Assembly (MLA), G Chinna Reddy. Raghuram told Reddy, who is from the Congress, that he wanted to offer puja at the village temple after his marriage ceremony. The MLA, who was one of the guests at the ceremony, assured Raghuram and asked the Dalits to follow him. But when Raghuram, along with other Dalits, reached the temple, the MLA was nowhere to be seen. Thinking that they had the MLA’s blessings, the Madigas entered the temple and offered puja. The next day when Raghuram’s mother went to distribute beetle leaves to the Boyas, as per the custom, she incurred the wrath of the Boyas. They threatened to kill Raghuram for daring to take Madigas into the temple.

Incidentally, Boyas, who are the dominant caste in Pathapally, themselves rank the lowest among the backward castes and have been seeking Scheduled Tribe status since 2012.4 The temple priest Krishnamachari performed the yagna for purification and reprimanded the Boyas for letting the Madigas pollute the gods. At night, the Boyas held a meeting and decided on a social boycott of the Madigas. Then began the saga of atrocities on Pathapally’s Madigas.

The Madigas have to walk through a kilometre-long road, a part of which passes through the Boya-dominated area of the village, to reach their colony at the lower end. Stones were thrown at them, they were abused and affronted with caste names and harassed in several other ways.

On 4 May, some Madiga youth went to Pebberu and informed the tehsildar about this harassment. In response, tehsildar Pandu Nayak, along with Prakash Yadav, sub-inspector of police (SI), and some policemen visited the Madiga hamlet, established a police picket and opened the doors of the temple to the Madigas. However, as soon as the tehsildar left the village, a mob of 300–400 Boya youth rushed in and attacked the Madigas in front of the SI and drove them towards the Dalit colony.

From that day, the harassment and assaults intensified. In order to avoid the daily ordeal, Madigas decided, on 1 June, to leave their homes and shift to the housing plots near the Pebberu–Kollapur road. These plots were allotted to them by the then Andhra Pradesh government in 2008. They erected hutments, brought building materials and began living there. However, the priest and the village revenue officer (VRO) incited the Boyas. They told them if Madigas lived at the upper part of the village, they would pollute the entire village and bring bad omen. In order to push them back to their old colony, the Boyas came in hundreds on 3 June and buried one Chinna Sayanna, who had died the previous night, right in the middle of the Madiga settlement. Madigas approached the police.

A contingent of 60-odd policemen headed by Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP), Vanaparthi came to the village the next day. But the police could not stop the Boyas burying another deceased, Godanna, again in the middle of the Madiga settlement. In fact, Godanna was buried right in front of the police. In protest, Madigas blocked the Pebberu–Kollapur road. The police, which had helplessly watched the Boyas bury their dead amidst Madiga hutments, lathicharged the protesting Madigas. Jitendra Reddy, SI, Pebberu, took 200 Dalits, including Raghuram, into custody and beat them black and blue. Even women were not spared by male policemen. Many were still being treated for injuries when I met them on 19 July.

Skeletons Tumble

The episode that began with an innocuous desire of a Dalit to enter a temple—with a 65–year old constitutional guarantee in place—exposed years of injustice and terror endured by Dalits. Close to the newly-allotted housing plots, one Narayana Madiga was allotted a patta of 1 acre and 13 gunthas of agricultural land. He began cultivating the land in 2001. The dominant Boyas could not stomach this. They started burying their dead on Narayana’s land and putting up memorial structures. While the Boya’s traditional burial ground lay just across the village road and had only three or four memorial structures built over several generations, the new burial ground had over a dozen such structures in a short period. Narayanawas harassed into giving up cultivation in 2007.

As we travelled into the Madiga colony, many more issues came to light. The village had a water tank but it supplied water to only Boya houses. There were separate borewells from which an underground pipe carried salty water to the Dalit colony. It opened into four pits with an opening each from where Dalits drew water. I had to request a Madiga lady to demonstrate how Dalits drew water to believe this appalling state-of-affairs. Beyond the Dalit village was a huge tank, which was said to have swallowed Dalit lands. Fifty-four acres belonging to Dalits were submerged, rendering them landless labourers. Such is the terror of Boyas that Madigas could not utter a word of dissent. The tank standing on their lands reportedly fetches over Rs 12 lakh annually from the auction for fishing, and irrigates Boya lands. What Madigas got in return was inundation of their houses during the rainy season during which serpents and other reptiles give them company. While the Boyas evicted Madigas from their own lands, they have usurped the village common lands with impunity and put up semi-permanent cowsheds and warehouses.

Interestingly, the sarpanch of Pathapally is a Madiga woman, Subhadra. She was earlier a cook in the village school’s mid-day meal scheme. Boyas had objections to her working as a cook but accepted Subhadra as sarpanch. In the current caste polarisation, Subhadra’s family is on the side of the Boyas. In contrast, one Boya, Pedda Vusanna, who was allotted a housing plot along with Madigas is on the Madiga side. Subhadra draws water from the borewells, much like her fellow Madigas, but does not speak a word against the dominant caste and, Vusanna has incurred the wrath of his fellow caste men, who have demolished his hut and thrashed his wife, son and daughter.

Tsundur Day and the Long March

The lathi-charge on 4 June catapulted Pathapally to the pages of district newspapers. The Kula Nirmulan Porata Samiti (Committee for the Struggle for Annihilation of Castes, KNPS) picked up the issue and formed the PDBNPS on 10 June to spearhead the struggle. It comprised KNPS, Telangana Praja Front (TPF), Praja Kala Mandali (PKM), Chaitanya Mahila Sangham (CMS), Civil Liberties Committee (CLC), Palamuru Adhyayana Vedhika, Telangana Vidyarthi Vedhika (TVV), Ambedkar Yuvajana Sangham, Democratic Teachers Federation (DTF), Madiga Students Front (MSF) and Jalavanarula Samrakshana Samithi. This new outfit organised a dharna in front of the collector’s office in Mahabubnagar on 23 June, but no one paid any heed to it. Dejected with the administration’s neglect, PDBNPS decided to hold an indefinite sit-in near the Ambedkar statue near the Pebber Mandal Office with a relay fast from 8 July. Even then none in the administration felt the need to speak to the agitating Dalits.

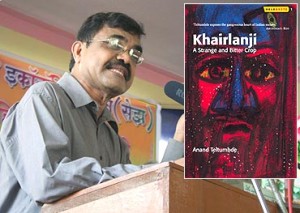

The KNPS requested me to intervene. I could do so on 19 July. I met the people on relay fast at Pebber and thereafter, accompanied by some KNPS and PDBNPS activists, went to Pathapally. I carried out my own investigations and addressed an impromptu press meet in the Madiga colony. The next day, Pathapally got prominently flashed for the first time in newspapers in Hyderabad and through a report in the Hindu, the Dalits’ struggle became national news. On 20 July, we had a formal press conference at Hyderabad which gave more exposure to the Madiga agitation.

All this stirred up the establishment, but negatively so. That very day (20 July) some goons feigning as MRPS (Madiga Reservation Porata Samiti) activists destroyed the pandal where the agitating Madigas were stationed. They had a scuffle with the Madigas and threatened them with dire consequences if they did not stop the agitation. But the goons had to beat a retreat before the resolve of the agitating Madigas. The administration, however, remained unmoved.

In order to create pressure on the government, the PDBNPS, after consulting me, decided to observe the 25th anniversary of the Tsundur massacre on 6 August and undertake an eight kilometre long march to Pathapally after the meeting at Pebber. The district administration, as mentioned before, decided to clamp down. The police cordoned off the entire area in the morning. Before starting off from the Hyderabad airport to Pebber, I called up the SP and the (special) collector to understand their plans and informed them my desire to discuss matters. As we reached Pebber, people began gathering and soon the crowd swelled to four to five thousand. The Additional Superintendent of Police (ASP) D V Srinivas Rao, who headed the police contingent, spoke with me and got my assurance that everything would be peaceful. After the speeches of the prominent activists in observance of the Tsundur Day, I addressed the gathering and gave a formal call for the long march to Pathapally. That provided the final spur to the peoples’ enthusiasm. Before we could manage to come out, they began marching towards Pathapally. Many joined in on the way and soon the slogan-shouting procession was almost two kilometre long. It reached Pathapally at 3 pm. The sloganeering touched high pitch as it entered the village. People walked into the temple, the entry to which had triggered off the entire episode. After taking a round of the Madiga colony, the procession converted itself into a public meeting on Narayana Madiga’s land. The two big pandals erected for the purpose could barely accommodate a fraction of the crowd.

A heavy downpour did not deter the Dalits. Around 5 pm, I, along with K Lakshmi Narayana of the University of Hyderabad, M Raghavachary, B Abhinava, and K Jayaraj of the PDBNPS, met the Special Collector and ASP. The discussion at the Scheduled Caste Welfare Hostel in the nearby village of Srirangapuram in Peppirair Mandal went on for three hours. The administration represented by the Special Collector Vanaja Devi and ASP Srinivas Rao showed exemplary understanding and displayed dignified appreciation of the struggle. It gracefully accepted all our demands, except those for charging Jitendra Reddy under the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act (SC/ST Atrocity Act) and suspending the RDO and the DSP under whose supervision the huts of Dalits were demolished. Rao wanted to discuss with the SP before making a commitment on charging Jitendra Reddy. Vanaja Devi assured us that the action would be taken against the RDO and the DSP as per the CCA rules. We accepted both assurances in good spirit.

The demands that were accepted include: (1) Fencing off the graveyard created by the Boyas on Madiga lands and not allowing any more burials there; (2) the heirs of Narayana Madiga to be given 23 gunthas of land, which they lost when the Boyas turned their land into burial grounds, within three months; (3) 45 pattas to be given to the Dalits within a week for making houses and construction of two-bedroom houses on priority under the government scheme; (4) 18 huts and one shutter that were demolished by RDO/DSP to be restored within a week; (5) Madigas who lost about 54 acres of land in the village tank will be compensated with land under the government’s land purchase scheme within three months if they have proof of patta or cultivation; (6) the fake cases filed against Madigas vide FIRs 65 and 67 of 2015 and another case under Section 107 against 23 Madigas to be investigated and withdrawn within 10 days; (7) Jannaiah, Erranna and others from Boya community to be charged under IPC 307; (8) Boya Mallesh and Anjanelu to be arrested under the SC/ST Atrocity Act according to the FIR 55 of 2015; (9) the temple priest Krishnamachari to be tried under the SC/ST Atrocity Act; (10) cases to be filed against the persons named in the last 11 incidents in the village; and (11) cases to be filed against the five families who buried their dead on the Madiga lands. The special collector, in addition, assured that she would work towards normalising relations between the Boyas and Madigas. The ASP also assured us of maintaining police vigil and protecting Dalits from any Boya reprisal.

Reminiscing Mahad

Comparison of Pathapally with the iconic Mahad struggle under the leadership of Babasaheb Ambedkar might sound audacious. But in many ways, the Pathapally struggle is reminiscent of the nearly nine-decade old iconic struggle. After an attack on the Dalits on 20 March 1927 in retaliation for their “polluting” the Chavadar tank, Ambedkar had consciously planned a satyagraha conference on 25 December. It envisaged a team of satyagrahis offering daily satyagraha at the Chavadar tank by drinking its water. However, some orthodox Hindus fraudulently managed to obtain a court injunction just a few days before the conference, claiming that the Chavadar tank was actually a Chaudhary tank, a private property, and hence not under the purview of the Bole resolution. The entire conference debated whether to go ahead with the satyagraha or not. An overwhelming majority of the 10,000 delegates that came for the satyagraha were determined to go ahead defying the injunction and court arrest. But eventually, on Ambedkar’s intervention, they relented and agreed to return without performing satyagraha.

The administration created a similar situation for us on 6 August by clamping Section 144. But sensing the resolve of the several thousand Dalits, it took a sensible stand and averted unseemly consequences. In Mahad, the situation was certainly far more congenial than at Pathapally for the Dalits to show resolve for their human rights. But unfortunately in giving up the satyagraha—as also not retaliate the attack during the previous conference—they lost an historic opportunity.

Pathapally, perhaps, reflected a learning from Mahad: the mode of struggle depends upon the adversary and that the state is not necessarily a friend of Dalits or even a neutral arbiter in social conflicts. The Mahad struggle had got strangled into court battles which when won after 10 years proved to be pyrrhic. Pathapally was surely more complex than Mahad. While Mahad was focused on a symbolic assertion of civil rights of Dalits, which they had secured, Pathapally involved actual civil and criminal issues against the dominant community. Mahad had largely pitched itself against the orthodox Hindu society whereas Pathapally was clear that it was confronting both the dominant community as well as the state.

Mahad had a largely non-partisan colonial state to induce a notion of neutrality, but Pathapally had to knowingly deal with the neo-liberal state, which characteristically tended to ignore the weak and shelter the strong. It could only bend under the pragmatic exigencies of public pressure. Pathapally reflected learning from its predecessors with which it could strategise and secure victory in one go—something Mahad could not. Such advancement in strategy and execution—as well as their results—shows Pathapally as an advancement over Mahad and as a movement that learnt from its predecessor. But all this does not rob Pathapally of its similarities with Mahad. Indeed, Pathapally could well be seen as Mahad of the 21st century!

While it is shameful for India to need Mahads, it may be necessary for Dalits to herald a new genre of Dalit movement.

Notes

1 Tsundur in Guntur District of Andhra Pradesh became infamously associated with a gory caste atrocity on 6 August 1991 in which eight Dalits were hacked to death by upper caste people.

2 Bole Resolution, so called because it was introduced by SK Bole, a noted social reformer of those days. It was passed on 4 August 1923, stipulating that untouchables were authorised to use wells, dharmashalas, schools, courts, administration offices, and public dispensaries. See Jaffrelot (2000).

3 The most numerous Dalit sub-caste in Telangana, to which all Dalits in Pathapally belonged.

4 See, for example, the Hindu (2012).

References

Jaffrelot, Christophe (2000): Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste, London: Hurst and Co, p 46.

Hindu (2012): “Valmikis, Boyas Seek ST Status,” the Hindu, 21 December, viewed on 12 August 2015, http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-national/tp-andhrapradesh/valmikis-boyas-seek-st-status/article4224754.ece.

http://www.epw.in/commentary/pathapally.html

Leave a Reply