Book review: The Last Word

Each state gets two chapters, one to explain the Left’s early achievements and the second to track its later debasement into patronage politics, insulated from mass movements.

The first half covers colonial and immediate post-colonial times, and the second explores Kerala and West Bengal, both ruled by the Left for long stretches of time.Book-The Phoenix Moment: Challenges Confronting the Indian Left

The first half covers colonial and immediate post-colonial times, and the second explores Kerala and West Bengal, both ruled by the Left for long stretches of time.Book-The Phoenix Moment: Challenges Confronting the Indian LeftAuthor: Praful Bidwai

Publisher: Harper Collins

Pages: 600

Price: Rs 407

Massive research, penetrating analysis, strong and clear arguments and a sparkling narrative had always characterised Praful Bidwai’s writings, from weekly columns to scholarly monographs. The qualities are more than evident in his last and posthumously published history of the Indian Parliamentary Left, from its inception in 1925, to the present. The first half covers colonial and immediate post-colonial times, and the second explores Kerala and West Bengal, both ruled by the Left for long stretches of time.

Each state gets two chapters, one to explain the Left’s early achievements and the second to track its later debasement into patronage politics, insulated from mass movements. Bidwai is far more appreciative of the Left in Kerala, which it governed intermittently, than in West Bengal, which it ruled for 34 continuous years. Tripura, perhaps the most remarkable instance of Left governance is, unfortunately, missing.

The research is stupendous, spanning party archives — sadly, not many inner party documents, most of which are kept adamantly secret — newspapers, historical works, as well as analyses of Indian and global politics from diverse perspectives, and intellectual and political debates around socialist and Marxist theories. Bidwai’s own intimate familiarity with all this adds an unusual historical and conceptual depth to the account. The mode of production debates of the 1970s, about whether to characterise the Indian economy as capitalist or as semi-feudal, for instance, are succinctly summarised in an appendix.

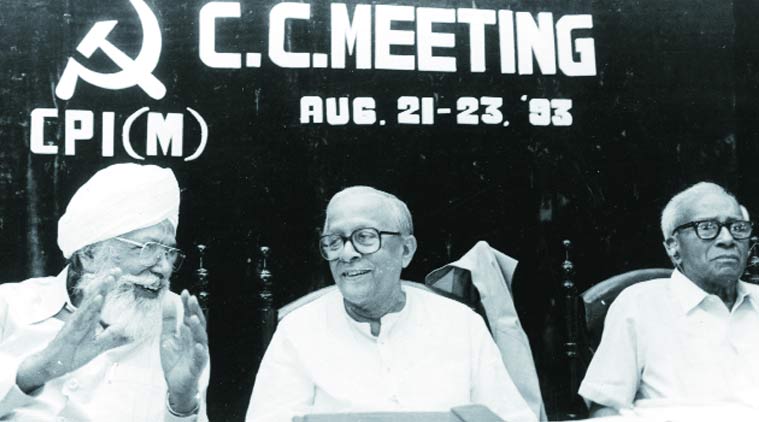

Harkishan S Surjeet (left) with Jyoti Basu and EMS Namboodiripad at the 1993 CPI(M) central committee meeting, BangaloreThe book elaborates the current crisis and concludes with thoughtful and sound suggestions about how to overcome it — hoping that the Left is still capable of listening to them. The focus is on the CPI and the CPI(M) but very often they are intertwined with socialists, social movements, independent workers — organisations and left insurrectionaries — about all of which Bidwai was amazingly well-informed.

Harkishan S Surjeet (left) with Jyoti Basu and EMS Namboodiripad at the 1993 CPI(M) central committee meeting, BangaloreThe book elaborates the current crisis and concludes with thoughtful and sound suggestions about how to overcome it — hoping that the Left is still capable of listening to them. The focus is on the CPI and the CPI(M) but very often they are intertwined with socialists, social movements, independent workers — organisations and left insurrectionaries — about all of which Bidwai was amazingly well-informed.

Surprisingly, few scholars have so far written a history of the Indian Left. This 90-year-old history — ironically, coterminous with that of the RSS, the Other of the Left — however, holds an impressive record of anti-imperialist politics, massive working class and peasant mobilisations despite tremendous repression in colonial and early post-colonial times, significant cultural movements, insurrections as well as governance with a difference (for some time, at least) of three states, and the critical national role played by the Left as a major force of opposition. Bidwai provides a rich and complex account of this history.

This was a particularly difficult book to write when the Left seems to face something like a terminal crisis. For Bidwai, this is not just an electoral failure but an existential crisis of identity. Bidwai’s narrative is tensely poised between affiliation and opposition, between fervent appreciation of Left achievements and bitter anger against its self-imposed limits — some of them conjunctural, some mid or long-term and some structural, almost constitutive. Among the former would be what Jyoti Basu called the “historic blunder” of 1996, when the party prevented him from heading a government at the Centre. Bidwai invokes the missed chance somewhat repetitively. Factionalism, leading to the split of 1964, and to the recent inner-party violence in Kerala, would be another instance.

Among the former would be what Jyoti Basu called the “historic blunder” of 1996, when the party prevented him from heading a government at the Centre. Bidwai invokes the missed chance somewhat repetitively. Factionalism, leading to the split of 1964, and to the recent inner-party violence in Kerala, would be another instance.

More serious than many other tactical blunders was the new industrial policy of 1994, an embrace of neoliberal economics and the China model, in obedience to national and multinational capitalist commands, and entailing ruthless violence against subaltern classes. The momentous change in policy orientation was adopted without any public debates on its necessity or considering alternative possibilities of development. This is also partly related to the deeper constitutive problem of Left adherence to the principle of “democratic centralism”.

Another long-term problem lay with restless changes in patterns of political or electoral alliances, often dictated by Soviet calculations in earlier times, or with highly conflicted and incoherent stances on India’s nuclear ambitions and nuclear energy. Bidwai shows how these flow from a seriously flawed understanding of ecological and human consequences and from privileging national ambitions over both concerns. He is particularly well informed about this issue.

Another serious problem has been the relative neglect of unorganised labour, especially agricultural labour in West Bengal. Fairly soon, land reforms degenerated into base-building among the small and prosperous peasantry alone. Panchayats were increasingly annexed to party politics. West Bengal has a poor showing for public health and education, for empowerment of women, the lower castes and Muslims. The celebrated Kerala model can boast of far more impressive social indicators of real progress but it, too, was exhausted by economic stagnation.

The most serious structural limit relates to the Left’s crippling theoretical deficit. Since its birth, it has clung to Stalinist orthodoxy — the most impoverished version of Marxism — and isolated itself from far richer socialist and Marxist strands, as also from feminist and Dalit critical social theories. Consequently, it could not contribute to international communist doctrines from an Indian perspective. At the same time, an obstinate fidelity to the Soviet line made it incapable of theorising Indian political and social realities, adivasis, caste, gender, religion, communalism, the environment and the militarisation of Kashmir and the Northeast.

In short, it developed no serious understanding of any major and relevant dimension of Indian experiences. This stands in puzzling contrast with its earlier formidable skills in mass mobilisation. The Soviet collapse, consequently, deepened political incoherence. At present, there is no vision, only electoral calculations for recovery. Bidwai considers that Left governance, at its best, approximated the aspirations of Nehruvian secular nationalism: a strong

developmentalist state with investments in public sector enterprises in large industries but offering little by way of social welfare or radical reform in fundamental class relations. As that vision eroded, the Left turned to economic conservatism instead of exploring new socialist or social democratic alternatives.

The Phoenix Moment, nonetheless, staunchly envisions the resurgence of a reinvented Left — without which, for Bidwai, India’s future is doomed.

- See more at: http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/books/book-review-the-last-word/#sthash.BCks4K7D.dpuf

Leave a Reply