Saket college in Ayodhya, 60 teachers short of requirement

HERE’S LOOKING AT US

Jyoti Punwani

It was on October 3 that Ravish Kumar, NDTV India’s most popular news anchor, began his series on the state of our universities: Class mein nahin guru, Bharat banega vishwa guru!

He’s still at it. In what must be a record for TV news anywhere, Kumar has managed to telecast 19 episodes on this topic on Prime Time, which airs at 9 every night.

In a typical episode, two or three colleges in different states are covered. Sometimes, the entire episode is devoted to a college like Harish Chandra PG College which was established in Benares in 1866 by the founder of modern Hindi, Bharatendu Harish Chandra, as a school with five students.

When The Hoot spoke to him, the anchor seemed totally immersed in his subject. Luckily for this reporter, a bout of fever had freed him from the routine he’s been following since he began the series: viz, starting research at 6 am to be able to wrap up by 2pm, when colleges close, then compressing 8 hours’ work for a 20-minute news show.

“I’ve had no time to read the papers all these days,’’ admitted Kumar. His fever meant he could enjoy the luxury of talking about what can be called his `magnificent obsession’.

He had always wanted to do a show on higher education, said the anchor known for going off the beaten track. Somehow, he couldn’t get the right format. Debates with educationists on the selection of VCs, and such like, didn’t appeal to him. He needed to portray the situation visually.

Ravish KUmar laments the absence of teachers in univeristies everywhere

Passing by a girls’ college in Sonepat during some other coverage, he had wondered what it must be like inside – 5000 girls getting higher education – but had not managed to stay back to find out. Discussions with students during his UP election coverage too hadn’t seemed enough.

He was often called to colleges to address students and would go there to find out what students felt, but had never got an idea about the full picture of higher education.

What had stuck with him was Delhi University Professor Apoorvanand’s advice to have a look at DU’s colleges: “You’ll find department after department lying bereft of professors.’’

A September 30 report in The Guardian on the poverty of American professors became the trigger. Kumar decided to find out the situation here. The October 3 episode took viewers into the small windowless rooms full of books, clothes, bottles of dals, gas cylinders and dusty old bags,in derelict structures next to filthy surroundings, that the 6500-odd ad hoc and guest lecturers of Delhi University are forced to call home.

With monthly salaries ranging from Rs 60,000 (guaranteed for a four-month semester) to Rs 25,000, they are left with little option but to skimp on everything, including their own marriage. For, they have no idea whether they will be employed in the next semester.

That first episode gave a glimpse of almost everything that was to follow: 30-70% teachers on contract across states; “self-financed college teachers’’ in Punjab whose salaries come exclusively out of students’ fees; teachers who pay more to the illiterate hired hands on their fields than what they themselves earn; government post-graduate colleges in Chambal where contract teachers called atithi vidvan earn Rs 8-9000 after having worked for 15 years; the different rates per day for the different types of atithi vidvans in Madhya Pradesh… What remained in Kumar’s mind was the lowest rate for a Sanskrit atithi vidvan of Rs 275 per day in a state where the minimum wage for an unskilled worker is Rs 274.

For Kumar, the series has been a discovery. “Imagine a class full of girls all neatly dressed just waiting all day for their teacher to come; imagine a tribal girl cycling 70 km every day to college only to find out that there’s no teacher. Such beautiful structures – people pay Rs 100 just to have a look around Sampurnanand Sanskrit Vishwavidyalay in Benares. For many of these universities, land was given by citizens who invested more than any government. A Mumbai businessman spent Rs 5 crore for a college in his village in Rajasthan. It has no teachers. This government makes such a fuss about Sanskrit, but refuses to recruit teachers for it.

Sampurnanand Sanskrit Vishwavidyalay: beautiful building, no teachers

“Madhya Pradesh’s Atithi Vidwans (numbering more than 5000 out of 7677 posts) must report to work come what may, even if they’ve just had a major operation. In Rajasthan, permanent teachers are sent to colleges which have none, to wrap up a year’s course in a week. In Amravati, teachers earn between Rs 5000 and 8000. In K. B. Post-Graduate College in Mirzapur, where Home Minister Rajnath Singh studied and taught physics, there is no teacher in the physics department.’’

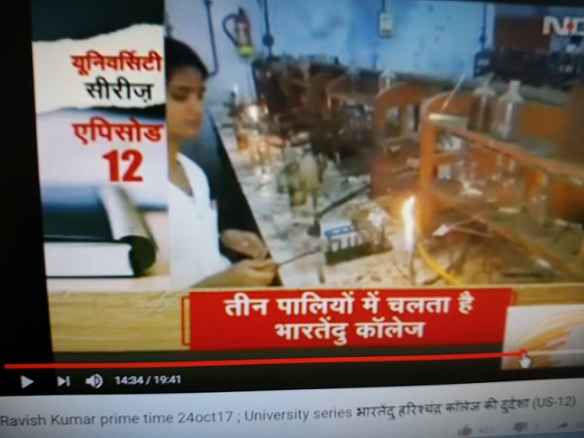

Lab in the college were Rajnath singh studied and taught.

Successive governments have made universities into “factories where merit is crushed’’, concludes Kumar. “This is deliberate, it’s not negligence. You think education ministers don’t know all this? The state is punishing the poor and there’s no protest about it. The system ensures that a poor man’s child will remain poor. Parents spend their life savings to get their children educated and there are no teachers for them. A couple of students may make it to TISS or JNU; a rickshaw puller’s son may get into the IAS, and stories will be written about him. What of the lakhs who don’t get even clerks’ jobs?’’

If his findings have overwhelmed the veteran TV journalist, what has left him puzzled and angry is the lack of protest. “Why don’t teachers say they can’t carry on in such circumstances? How can one teacher teach all subjects in one department? Why aren’t Hindiwallas upset about the condition of Harish Chandra College, named after Bharatendu Harish Chandra? Lal Bahadur Shastri studied there. It has hardly any permanent teachers, and a ladies toilet was built there just last year!

“I see no anger anywhere, not even among parents. Don’t tell me they are unaware. For them their children’s education means everything. And don’t give me the excuse that they are scared. They are willing to speak up about demonetisation. Ask them about the Hindu-Muslim issue and then see how they let fly. Here, their children’s future is being destroyed. Why aren’t they on the streets? Or at least questioning their MLA?’’

The response of students to his series has left Kumar disillusioned. Some contacted him to request that he feature their engineering colleges too. “But when I ask for details, they’re unwilling to provide them, saying they’ll get into trouble. This is the quality of citizenship! If they are so scared even to give information anonymously, the idea that youth is revolutionary is a myth. India’s youth has let down Indian democracy.’’

He makes an interesting distinction between Delhi’s students and those in the rest of the seven states he has covered. His series covered the recent protests at the School of Planning and Architecture.

“Delhi’s students have an awareness of entitlement in the democratic system. By protesting, they are actually benefiting all students. The tragedy is JNU is demonised because of its protests. Instead of encouraging their students and children to exercise their democratic right to expression, teachers and parents discourage them. Society has become slave-like. How will such citizens value an independent media?’’

But the media must share the blame, says Kumar. “Do we cover student and teacher protests outside the big universities? Teachers in Ghaziabad have gone into depression. They haven’t received salaries for 16 months and keep asking for some coverage.’’

On the one hand, is the lack of anger among those affected; on the other, is the indifference of those responsible for this criminal negligence. No minister or even bureaucrat has contacted him. “To my surprise, the only MP who took note was Shashi Tharoor, who tweeted that there should be a national debate on this issue. I too had hoped that would happen. But this is not an issue for anyone.’’

But it is obvious that those directly affected are watching. Acting on information from friends in Delhi University, he sent his reporters and stringers (see box) from Delhi to Rajasthan to Patna. By then, his team started picking up stories. But even as he began to feel he would not be able to make it beyond the 11thepisode, tips from students and teachers helped him. Retired teachers help him with facts and figures about the number of vacancies and salaries.

But what about general viewers? “My inbox is not overflowing, but there has been the normal feedback.A few bhakts have told me I’ve opened their eyes. And there are those who complain that I’m targeting BJP-ruled states. They aren’t angry at the situation, but only want me to show that students in Congress-ruled states are being destroyed too!’’

What, then, has kept him going over 19 episodes? And hasn’t NDTV told him to stop? “I don’t tell NDTV what I’m going to be airing and they never ask. Perhaps no other channel would have allowed someone with zero TRPs this,’’ he laughs, adding, “I’m doing it for myself. Once I start a report, I must show everything. I’m like a beat reporter. I would have liked to work on this like a newspaper would – put 25 reporters on the job and present a complete picture. I wish I could cover Bengal, the North East, Kashmir. But I don’t have people there. In Gujarat we have just one reporter and he’s busy with elections.’’

Isn’t he ever tempted to get into the news of the day? “No, I don’t let all that decide my relevance,’’ he replies.

Doing this series has been an enriching experience, says Kumar. “I’ve learnt so much. My reporters and stringers have also enjoyed doing this. Besides, I know there is a section of viewers who are watching. Somewhere, people are taking note. A college they pass by every day without a glance, has suddenly become newsworthy. A small protest taking place somewhere is getting strengthened.’’

What is it like to watch the series? One has to make a conscious effort to tear oneself away from the day’s controversies to tune in for yet another episode of absent teachers and crumbling colleges. But rarely does one regret the decision. The passion that Ravish Kumar and his team have for the subject makes it riveting viewing.

The 17th episode for instance, had shots of grumpy school teachers forced to work as pujaris at Haryana’s Kapal Mochan Mela. In the same episode, one heard with disbelief a professor’s statement that since the state of Chhattisgarh was founded, no permanent teacher had been employed in its capital’s Durga Mahavidyalay which has 3000 students and 12 political heavyweights as alumni.

Every episode leaves the viewer feeling disturbed. Given the absence of any process of higher education, how will today’s social media-addicted youth learn to discern between reality and propaganda? The questions raised by Kumar challenge the claims of this government on a more serious level than do debates on prime time, because they aren’t raised in a one-shot telecast, to be forgotten the next day.

In one episode, Kumar mocks Modi’s suggestion, made soon after he took over, that we should export “top-class teachers’’ to the world. The theme of the series itself is a take on Modi’s boast, made both here and abroad, about India becoming a vishwa guru.

The Ayodhya episode featuring Saket College was aired two days before Diwali, coinciding with UP CM Yogi Adityanath’s announcement of a grand Diwali celebration in the holy city. The scenes shot inside the college were a scathing comment on the CM’s priorities.

That this series manages to have this effect is creditable given the constraints it faces. Apart from the lack of manpower, colleges were closed for Diwali for most of its duration; lack of internet connectivity in some areas (reporters went as far as Kolhan in Jharkhand) meant feeds coming in as late as 7.30 in the evening.

Students use a lab by candlelight in Bhartendu Harish Chandra College, Varanasi.

Most of the filming of college interiors has been done with mobile cameras; a regular photographer’s team would not have been allowed. In Ayodhya’s Saket College, the authorities insisted there were six toilets for the 4000-odd female students inside the common room but refused to let the reporter go there.

Yet, the most enduring memory of the series has been visual: rooms full of old bottles and broken fans; peeling plaster on the ceilings, dirty toilets and the principal’s clean office. One visual refuses to fade away: the sight of burning candles casting a ghostly glow across a dusty old laboratory and its rusty basin full of stagnant water, as students talk about how they can never get results from their experiments as they have neither enough equipment nor chemicals.

http://www.thehoot.org/media-watch/opinion/ravish-kumars-magnificent-obsession-10370

November 8, 2017 at 5:42 pm

The plight of teachers and college education is being painstakingly brought out by Ravish Kumar. His reports should be analysed and corrective neasures should start immediately