The project is said to be in serious violation of several legal provisions

- No clearance secured from the Environmental Impact Assessment Authority as required under a notification in 2006 by the MoEF.

- Denial of compensation is against the provisions of the Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act and violates principles of fairness

- Land Acquisition Act provided that if acquired land was not used for the specified purpose for a period of 10 years, it was to be returned to the owners or their heirs.

- The Sardar Sarovar Project, for which land was acquired, has been completed. Further use of this land is against rules framed by Narmada Control Authority

- While land acquired for a Narmada canal may be in the ‘national interest’, can construction of a three-star hotel be deemed to be so?

- No social impact assessment was conducted for the 12 km long ‘man-made lake’ or Garudeshwar weir, the width of which is still undecided even as work on the weir has commenced

***

He’s been there for as long as he can remember. He was 25 when officials first turned up to tell his grandfather that they would have to vacate the land. Now he is 79 and he still lives there and cultivates the small holding by the river Narmada. Neither the Sardar Sarovar dam, barely three kilometres away, nor Vadodara, 90 kms from the Narmada Valley, has made any difference to Ukkad Magan. No, not even the Gujarat ‘model of development’.

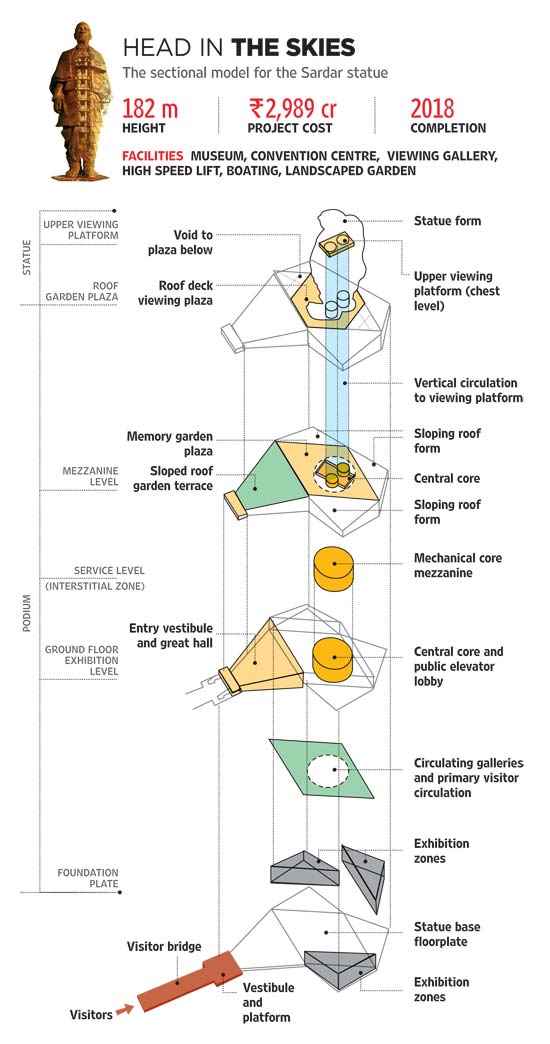

But now he and 500 other households in Kevadia village again face the prospect of eviction. This time to make way for PM Narendra Modi’s ambitious Rs 2,989 crore project to instal the world’s highest statue, the Statue of Unity. Villagers refused to receive the eviction notice two weeks ago when officials turned up to deliver them in person. But it’s only a matter of time before they return. The notice calls upon them to vacate the land “immediately”—no time-frame was mentioned.

Gujarat government officials claim the land was acquired 54 years ago for the Sardar Sarovar project. “This is government land, these people are encroachers,” says an executive engineer of the Sardar Sarovar Nigam Limited (SSNL) entrusted with the task of overseeing construction by engineering giant Larsen & Toubro.

Magan disputes the claim. As he shoos off the birds trying to feed on the harvest-ready crop, he informs you, “When the officials first came in 1961-62, they had promised compensation and told us we would have to move out temporarily. But they never returned thereafter.” The villagers pay house tax even now and also pay for the electricity they get.

The six villages by the Narmada likely to be affected by the project’s first phase are inhabited by Tadvi tribesmen who have been here long before the Sardar Sarovar dam came up. Villagers claim that when they sought proof of acquisition from the officials, they admitted that they did not have the relevant documents to prove the land had been acquired.

***

It’s a January afternoon and there isn’t a soul to be spotted anywhere around the dry riverbed, barring four policemen wandering lazily under the bright afternoon sun. The khaki presence was the only indication that on the ‘Sadhu Bet’ river island, work is about to start on the statue. It’s not just a statue, of course. The project visualises a museum, an artificial lake, a memorial garden, a viewing gallery on top and a three-star hotel.

Indeed, a huge billboard has come up outside Magan’s house announcing that a 128-room, three-star hotel called ‘Shrestha Bharat Bhavan’ is coming up on the spot. A little distance away, Magan impassively informs us, “We are told this is the spot earmarked for the hotel parking lot, with enough space to hold 500 cars.”

The riverbed around the island looks parched, there’s hardly any water. On top of the mound, a few engineers busy themselves with some equipment. “These people are encroachers. The hotel is an enabling work related to the statue and will be built over 9-10 hectares, all of which has been acquired,” says H.R Zoravia, the SSNL executive engineer supervising the Statue of Unity project in Kevadia. Asked to produce proof of the land acquisition, he replies that they were available but cannot be disclosed.

Local Congress leader Dineshbhai Tadvi though begs to differ. He claims the government doesn’t have any proof that the land of these six villages was acquired under the then Congress government in 1962-63. Even if some of the land was acquired for canals or such (which never came up), it cannot be used for any other purpose without permission from the competent authority, say activists and lawyers. But no permission has been secured, no impact assessment conducted nor public consultations held before work started on the statue. Land rights activists have recently served legal notices to all those involved in the statue construction in a bid to get a stay on the demolition of these houses.

Police has been deployed in large numbers around the site and in the neighbouring villages where tribals are agitated against their forced eviction. State reserve police camps have come up at several places over the past two weeks. Kevadia resident Nareshbhai Tadvi says that a moustachioed supervisor of l&t has been threatening villagers with dire consequences if they don’t vacate soon.

***

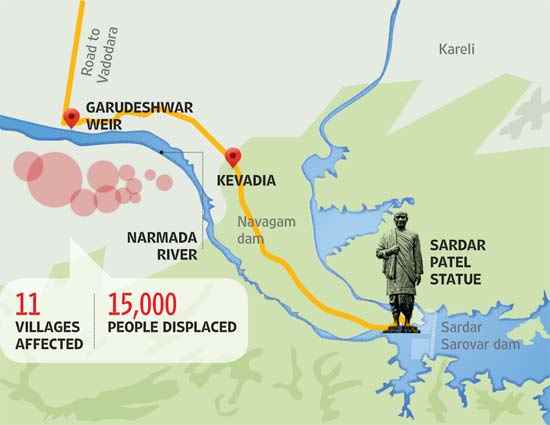

The official website and glossy booklets dwell on elaborate plans for the towering Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel statue, surrounded by an enormous 12 km ‘man-made lake’. The idea is that statue visitors will be able to go boating around it. The lake is on the Garudeshwar weir, which will displace around 11,000 tribals inhabiting 11 villages in the valley, according to a petition filed with the National Green Tribunal by rights activists. It states that those in the villages of Garudeshwar, Gabhana, Kevadia, Vagadia, Navagam, Limdi, Gora, Vasantpura, Mota Piparia, Nana Piparia and Indravarna will lose their land and livelihoods if the man-made lake comes up around the statue. The next hearing is due on February 4.

“If the statue has to have water around it, the weir will not be able to pump all of it back for irrigational use. Constructing the weir will fail in its original purpose of making better use of the water, as it will have to hold it back around the statue,” argues activist Rohit Prajapati.

“If the statue has to have water around it, the weir will not be able to pump all of it back for irrigational use. Constructing the weir will fail in its original purpose of making better use of the water, as it will have to hold it back around the statue,” argues activist Rohit Prajapati.

Work on the weir is said to have commenced ‘illegally’, without obtaining any clearances or conducting any impact assessment studies. Although officials maintain the weir was proposed way back in the ’80s during the Sardar Sarovar Dam’s inception, Shekhar Singh, permanent member of the Narmada Control Authority confirms no clearance for it was obtained while permission was granted for the dam in 1987. In a letter to the MoEF on March 24, 2013, Shekhar demanded immediate stoppage of work on the weir (whose width too is yet to be determined), citing adverse consequences, like the villages it will submerge and fisheries it will affect in downstream areas. Yet, work on the weir continues.

The government has also not taken any step towards rehabilitation/resettlement of the 11 villages spread over 1,000 acres, whose lands will be temporarily submerged by the weir. This despite the official map of the Garudeshwar weir clearly acknowledging these 1,000 acres as part of the ‘water body’. “Once our crop is washed away, there is no way we can sow them again. Our produce for the season is lost. Once our houses are destroyed, are we expected to build them again and wait for the next flood to wash it away?” asks 85-year-old Ghalajbhai Tadvi in Mota Pipariya. People living around the weir have not even been notified about the project or the losses they might incur.

***

The SSNL, after repeated protests by the tribals, has offered compensation but only to those whose lands will be permanently submerged. It has offered to provide them, and those whose lands it claims to have acquired in the ’60s for the canal, land elsewhere in compensation. However, the villagers say these plots, 15 kms away from their present dwellings, are the rejected, leftover land from the rehabilitation undertaken in the 1980s, mostly hill terrain. “Modi chahta hai ki garib ko hatao, garibi nahin (Modi wants to ensure the poor are eliminated, not poverty),” says Ganesh Tadvi of Kevadia village, who will lose part of his land to the statue and the remaining to the weir.

By Pavithra S. Rangan in Narmada Valley, Gujarat

Leave a Reply