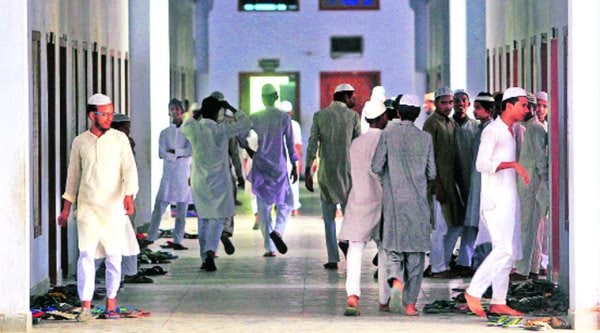

At the Madrasatul Islah in Azamgarh. ( Source: Express photo by Vishal Srivastav )

At the Madrasatul Islah in Azamgarh. ( Source: Express photo by Vishal Srivastav )Only 4 per cent of Muslim children go to madrasas in India, as per the Sachar committee report. That was a fact BJP’s Unnao MP Sakshi Maharaj didn’t mention when, addressing a meeting in Kannauj last month, he alleged that madrasas across the country are imparting “education of terror” and “love jihad”.

Deep in Saraimeer, a much-talked-about part of Azamgarh since many alleged Indian Mujahideen activists were traced to it, is Madrasatul Islah, the oldest and one of the largest madrasas in the area, with about 1,500 students. Set up in 1908, it once had on its rolls leading Islamic scholars such as Shibli Nomani and Hamiduddin Farahi.

This day, its senior-most class is attempting to answer a more basic question on the blackboard — “Who was the first Indian to use the mobile phone?” Several students spring to their feet with the answer to that little-known fact: “Jyoti Basu, in March 1995”.

Cellphones play a big role in their lives, the students admit. While even a decade ago students here would have been loathe to talk about watching television, or serials such as CID or Dastak, now, under the watchful gaze of their English teacher Dr Iqbal Ahmad Sanjari, they discuss the pros and cons of WhatsApp, almost disdainful that these questions are being asked of them.

The boys between the ages of 17 and 19 years see themselves as one with the larger world. Almost all are wired into technology and media, particularly television.

As Dr Sanjari tells students about the six topics to be covered in English essays the coming week, subjects such as ‘Science as Master and Slave’, ‘Student Unrest in India’ and ‘Islam and Politics’ find enthusiastic takers.

Mohammed Tariq, 17, says he finds technology “mechanising” lives and minds “disturbing”. “I want to go out into the world and be useful to society after I complete my graduation,” he says.

Abu Noman (17) worries about being a “machine ka ghulam (slave to machinery)”. “If the calculator and Internet fail, everything does,” he points out.

Rishad Ahmed (18) wants to pursue Arabic literature and eventually do a doctorate from Aligarh Muslim University, a much-coveted instituion at the madrasa.

The students say technology has allowed them to see things they could not before and interact with others outside their immediate physical setting. But far more than affordable technology, it is policy that has given the students here a sense of mobility.

The “mainstreaming” of madrasas by the Centre in 2008 has given them dreams of real educational and then social mobility. In December 2008, the UPA I government brought certificates issued by state madrasa boards on a par with certificates issued by state boards, making it possible for students like those at Madrasatul Islah to take admission in Central and state universities.

The possibility of migrating to ‘regular’ education programmes and degrees has changed the madrasa world.

Says Sanjari, “At the Class XII equivalent level, we teach up to BA Part I programme to give our students a headstart. Science, English and Mathematics are given great importance.”

Dr Akhtarul Wasey, former dean, Faculty of Humanities and Languages at Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia University, says, “Madrasa students comprise about 15-20 per cent of the intake annually in our university, mostly In Islamic Studies and Arabic, but they increasingly want to get into Political Science, History and Sociology. They are usually very hardworking.”

Azamgarh itself is still struggling to shake off its tag of terror, particularly since the 2008 Batla House encounter in Delhi. Mulayam Singh’s choice of Azamgarh as his constituency was to give the area “confidence” and make a point, but those who live here and have it on their birth certificates, still resent the label of the Batla encounter of 2008, which has stuck.

So the prospect of mobility has also brought with it frustrations of not being able to integrate as fully or equally as they would want to. Says Sanjari, “It is still just the really big Central universities which recognise these certificates. Plenty needs to be done and universities still dodge the question of allowing an affiliation, despite the rigour and our standards being very high.”

Almost every student at Madrasatul Islah understands the nuances of this politics and is agitated by the attitude of the world outside towards them.

Asks Abdul Aleem, (17): “Why have the poor and backward segments of society not benefited proportionately from technological changes, and why have several fallen behind? Prejudice in India runs deep for several sets of people.”

Fazlur Rehman, 19, admits they feel boxed-in and in a trap. “As if poverty is not enough to tie us down, if we somehow get over that hurdle, we have to fight the maahaul (environment) that views our names and the Azamgarh postal code with suspicion.”

Classmate Iqbal Ahmed asks why the media unquestioningly plays into “old prejudices” and “repackaged and old agendas”.

According to Dr Sanjari though, there is a difference: it is the change in Azamgarh that has made it the focus of the new attacks. “It is precisely the educated Muslims who are now the target of attacks and are being pushed back,” he says.

The director of another well-known institution of Azamgarh, the 100-year-old Shibli Academy, also sees this happening. “Azamgarh was perhaps chosen to pinpoint and target because it has been a centre imparting education and turning out scores of educated and qualified persons — Muslims included,” says Dr Ishtiyaque Zilli.

Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru both were frequent visitors to the Shibli Academy, and authorities eagerly show you the tree under which Nehru used to bathe when he stayed here.

Madrasatul Islah principal Maulana Sarfaraz Ahmed Islahi is not sure what more he can do to establish the institution as a legitimate school imparting education.

“We continue to tell everyone to walk through our doors and see how open things are in Azamgarh’s oldest and biggest madrasa,” he says. “Would you want to take more pictures?”

– See more at: http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-others/in-azamgarh-madrasa-talk-revolves-around-tv-whatsapp-higher-studies/99/#sthash.Kc1fkYe0.dpuf