Prepared in four days, report concluded “no illegal mining” was taking place along Tamil Nadu‘s coast.

A joint-inspection team from the Union Ministry of Environment and Forests and various departments of Tamil Nadu, including the mining department, prepared a report in four days to allegedly exonerate the state’s powerful sand-mining lobby, HuffPost India has found.

HuffPost India’s investigations reveal this “Joint Inspection Report” was an effort to derail a high-stakes state government investigation into illegal beach sand-mining cartels.

The sand-mining companies obtained this report via the Right to Information Act and used it to contradict the government’s stance in the Madras High Court.

The report’s conclusions were so surprising, that the amicus curiae – a court-appointed lawyer overseeing the case – questioned if officials had played “a collusive role to ensure that the mining companies escape liability for the innumerable illegalities committed by them.”

(Disclosure: This report also attacked this reporter for writing about illegal sand-mining on Tamil Nadu’s coasts. At the time of press, this reporter is fighting two defamation cases filed by a mining company. A detailed explanation may be found here.)

When Tamil Nadu’s then Chief Minister J. Jayalalithaa learnt of this errant report, she suspended eight government officials, including a former Chief Secretary of the state.

“There is a huge nexus and it is able to transcend parties and professionals”

Five senior officials told HuffPost India that this report led to the resignation of the Tamil Nadu advocate general A.L. Somayaji.

The following account, pieced together from over a dozen interviews and hundreds of pages of court records, illustrates how one arm of the government was used against the other, making it almost impossible for vulnerable mining-affected communities to get justice.

Of the eight suspended officials: K Gnanadesikan, former Chief Secretary of Tamil Nadu, has been reinstated as Industries Secretary and charges against him have been dropped. Atul Anand, then Commissioner of Geology and Mining, is now Commissioner for Social Security Schemes, but remains under investigation.

HuffPost India has been unable to establish the outcome of the remaining six inquiries.

A ninth official, C.V. Sankar, secretary for Industry at the time, was also involved in the preparation of this repor and signed off on its conclusions. Sankar escaped censure as he had retired by the time the Chief Minister’s office took action against the officials.

“There is a huge nexus and it is able to transcend parties and professionals,” said R Sridhar, Managing Trustee, Environics Trust who was formerly employed with the Atomic Minerals Division of the Government of India. “I have a hunch that they either are operating to extract something from the miner or responding to some court proceedings where officers are trying to save their skins.”

A Tale of Two Reports

In August 2013, the Collector of Tuticorin, Ashish Kumar, raided sand quarries in his district on the suspicion that some of the quarries were operating without licenses. He was transferred 8 hours after the raid, prompting an outcry in the media.

Chief Minister Jayalalithaa stopped all sand mining on Tamil Nadu’s beaches and constituted a special team, led by Revenue Secretary Gangandeep Singh Bedi, to produce a report on illegal sand extraction in five districts. His report would come to be known as the “Bedi Report”.

At first, Bedi moved fast – producing an initial report on mining in Tuticorn in a month. Yet, as the scope of his inquiry widened to sand-mining across the state, mining companies opposed his appointment, accusing him of bias in an affidavit filed before the court.

A single-judge bench of the High Court ordered that Bedi be replaced, only for the order to be stayed by a superior bench.

So thick was the red-tape around Bedi’s report that even the state government’s lawyers were seemingly unclear about its status.

But even as Bedi toiled over his investigation, a section of the bureaucracy was working to undermine his efforts by producing a report that would directly contradict his eventual conclusions.

On 22 July 2016, when the court-appointed amicus curiae, asked for a copy of the report, the court was told “the report of Mr. Gagandeep Singh Bedi’s special team is stated to be non-existent at present.”

When Somayaji, the state’s advocate general, stepped down from his position in August 2016, his successor R. Muthukumaraswamy told the court that the Bedi report did in fact exist. The Bedi report was submitted in a sealed envelope to the Madras High Court sooner after.

Excerpts of the Bedi report, quoted in court documents, accessed by HuffPost India, reveal explosive details: 575 acres of land were illegally mined and 90 lakh crore (90 trillion) metric tonnes of beach sand were illegally mined. Bedi did not respond to HuffPost’s request for comment.

But even as Bedi toiled over his investigation, a section of the bureaucracy was working to undermine his efforts by producing a report that would directly contradict his eventual conclusions.

This controversial report was called the “Joint Inspection Report”.

The Joint Inspection Report

On 1 February 2015, this reporter wrote an article in the Economic Times on the effects of sand-mining on Tamil Nadu’s coastline. The companies named in the article responded by suing the publication and this journalist for defamation. The cases are currently pending in the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court.

The conclusions of the Bedi report were not public at the time, but the mining lobby expected him to come down heavily on their operations.

This reporter’s story became a starting point for a parallel inquiry, written by a different set of government officials, to undermine Bedi.

On 25 February 2015, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change (MOEF), New Delhi issued a letter to the Director of their regional office in Chennai, C. Kaliyaperumal, as well as to the Principal Conservator of Forests, KS Reddy, to inspect and verify the allegations made by this reporter in her news article in the Economic Times.

Speaking of how one wing of the government effectively ambushed the other, a senior official closely connected with the case conceded that “mistakes were made.”

Kaliyaperumal wrote to the Commissioner of Geology and Mining, Atul Anand, the State Coastal Zone Management Authority, who acted with alacrity.

A month later on April 27 2015, Anand’s team readied a 17-page report which clearly contradicted the findings of the Bedi report. The team took only four out of an appointed six days to come to its conclusions, and the team signed off on the Joint Inspection Report on the last day of their inspection.

The Joint Inspection Report concluded that there was no illegal mining in the districts visited by the team, and quoted extensively from www.beachminerals.org – the website of the Beach Minerals Producers Association that represents the interests of sand-miners – to suggest that this reporter was motivated by a personal enmity with the mining lobby.

Joint Inspection Report into Sand-Mining in Tamil Nadu

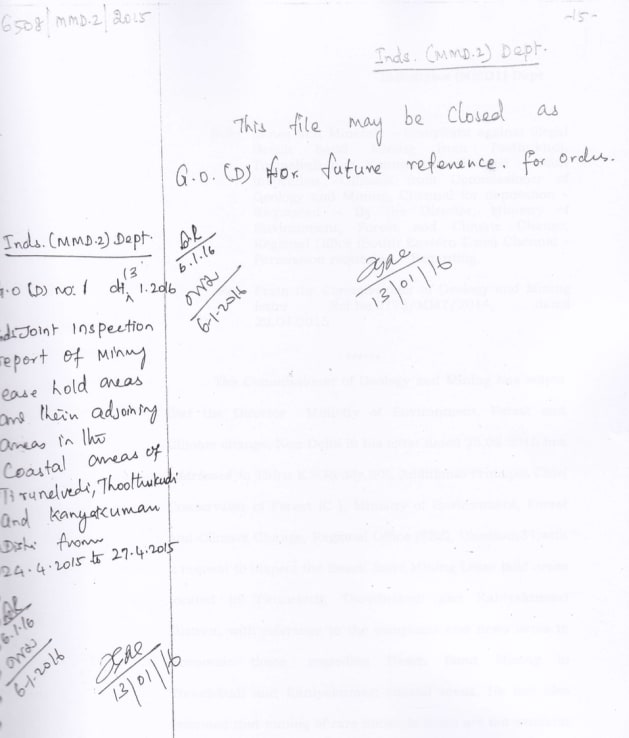

This Joint Inspection Report, which exonerated the mining lobby, was shared with the Secretary for Industry C.V. Sankar, who initialled it, and sent to Gnanadesikan for his “kind perusal”, who scrawled “This file may be closed as for future reference”, and signed off.

Soon after, the mining lobby quietly filed a Right to Information request and obtained a copy of this report.

Gnanadesikan declined to respond to a questionnaire sent by HuffPost India, Sankar declined to comment when HuffPost India approached him. Atul Anand’s office refused to share his official email address with HuffPost India or provide time for an appointment.

Anand also did not respond to a questionnaire texted to the official cell-phone number attached to his office.

An officer closely connected with the case said the preparation of the Joint Inspection Report was a consequence of a misunderstanding between the bureaucracy and the state government.

“Many times we do not know what the political bosses are thinking,” he said. “We cannot fight all the time.”

Alarm Bells

Even as two factions of Tamil Nadu’s famously opaque bureaucracy produced two separate reports, court hearings into the state’s sand-mining cartels continued apace.

In July 2016, advocate general A.L. Somayaji was appearing in court for the Tamil Nadu government, when the mining-companies filed the Joint Inspection Report in court to support their stance that no illegal mining was underway.

The state was in a bind: the Joint Inspection Report prepared by a team of state and central officers exonerated the mining companies, while another report – i.e. the Bedi report – came to the opposite conclusion.

On 18 July 2016, Somayaji wrote to the Industries Department, “Last week, the Writ Petitioners who are the respondents in the Writ Appeal filed a Joint-Inspection Report dated 27/04/2015 of the officials of the Central Government and the State Government.”

Letter by former Advocate General A.L. Somayaji

The mining lobby, Somayaji continued, was using the Joint Inspection report “in support of their case that there has been no illicit mining.”

The creation of the Joint Inspection Committee, and its report, Somayaji concluded, “is not only in violation of the order of the court but also adversely interferes with the constitution and functioning of the special team constituted by the state Government to investigate into the complaints of illicit and illegal mining.”

On 24 August 2016, soon after he wrote the letter, Somayaji stepped down. When asked about his sudden resignation, Somayaji told HuffPost India, “I cannot comment on the matter as I was Advocate General at the time.”

“Or are there other possibilities that the officials and the agencies have played a collusive role to ensure that the mining companies escape liability for the innumerable illegalities committed by them?”

Speaking of how one wing of the government effectively ambushed the other, a senior official closely connected with the case conceded that “mistakes were made.”

V.Suresh, the amicus curiae appointed by the court to oversee the case, was more direct.

“Is the failure of the official agencies to enforce the law, play their officially mandated responsibilities and to ensure effective monitoring of the functioning of the mining companies, merely indicative of inefficiency and lethargy?” Suresh asked, in a 2017 status report submitted to the court.

“Or are there other possibilities that the officials and the agencies have played a collusive role to ensure that the mining companies escape liability for the innumerable illegalities committed by them?”

The Chief Minister Acts

The repercussions of the Joint Inspection Report went far beyond the court. Chief Minister Jayalalithaa demanded to know how this report exonerating the sand-mining lobby was prepared.

Files were pulled out, an official with direct knowledge of events said, and the eight officials were suspended on 28 August 2016 – former Chief Secretary K Gnanadesikan and then Commissioner of Geology and Mining Atul Anand among them.

The ninth official, Industries Secretary C.V. Sankar had retired on 31 July 2016, and so escaped censure, despite signing off on the report as well.

In court, the embarrassed state government insisted that the Joint Inspection Report was incorrect, was prepared without their permission, and that illegal sand-mining was rampant.

“It is humbly submitted that, the state Government has not granted any permission to carry out inspection,” said Vikram Kapur, Principal Secretary to the government, in a subsequent submission to the court.

Kapur said it was impossible to produce a meaningful report on illegal sand-mining on a basis of a short four-day visit, and that the Joint Inspection Report provided no evidence to support any of its claims.

The Joint Inspection Report exonerating the mining companies, Kapur concluded, was “irrelevant to the task of the inspection.”

Affidavit by Tamil Nadu Industries Secretary Vikram Kapur disputing the Joint Inspection Report

Justice, Anyone?

The ease with which a cabal of bureaucrats stymied their own government’s investigations has activists in Tamil Nadu worried.

“We are expecting ‘sand wars’ to come before the ‘water wars’,” said Probir Banerjee, and expert on coastal ecology and co-founder of PondyCAN (Pondicherry Citizen’s Action Network) who is an expert on coastal ecology.

Banerjee described the ripple effects of sand-mining as “beach-o-cide”.

“The more of healthy sandy beach you have, the more it protects us,” he said. “But policymakers are allowing sand dunes to be depleted. Nobody wants to interfere or take action because it is mafia-driven and is too dangerous to touch.”

The Chief Minister’s office and the Chief Secretary did not respond to email queries or phone calls.

Meanwhile in court, the hearings continue.

https://www.huffingtonpost.in/2018/05/06/revealed-how-tamil-nadu-officials-made-up-a-report-to-aid-illegal-sand-mining_a_23428131/

Leave a Reply