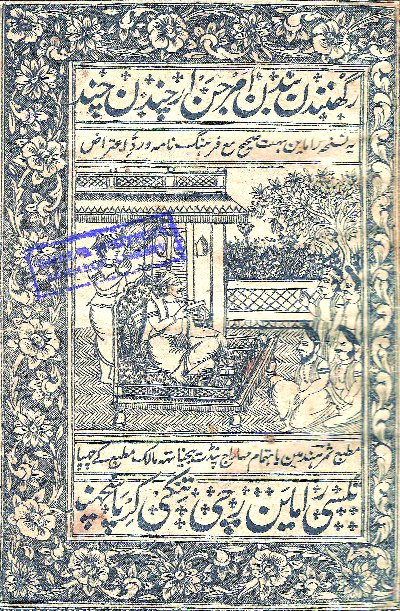

The earliest Urdu translation of the Ramayana, by Munshi Jagannath Lal Khushtar, was published by the Nawal Kishore Press in 1860. (Source: Thinkstock images)

The earliest Urdu translation of the Ramayana, by Munshi Jagannath Lal Khushtar, was published by the Nawal Kishore Press in 1860. (Source: Thinkstock images)

My mother remembers watching Ramlila tableaux in Lucknow where the actors spoke in immaculate Hindustani interspersed with flowery Urdu verses. By my childhood, as Urdu became “Muslim” and Hindi became “Hindu” and Hindustani became a casualty of their war, the secular elements had been leached out from the Ramlila. While still a fairly inclusive community-based neighbourhood celebration, it had become a religious festival. By the time I began taking my children to the Ramlila pandals, Bollywood had taken precedence over all else. Scale and spectacle dwarfed the content and the dialogue, which when not drowned by ear-splitting music, seemed to be inspired by poor Hindi films. The early influence of Parsi theatre, the florid Hindustani dialogue, the Urdu verses — not a trace of them remained.

The coming of Dussehra always reminds me of the references to the Urdu Ramayanas I had heard as a child, especially fragments by Brij Narain Chakbast that several elders could recite from memory. I remember my grandfather reciting the scene depicting Ram as he takes leave from Dashrath before going for banwas, his voice rising and falling as though he was reciting a soz: Rukhsat huwa woh baap se lekar khuda ka naam/Raah-e wafa ki manzil-e awwal hui tamaam (He took leave of his father taking the name of God/And thus the first stage of the path of loyalty was crossed). Kaushalya’s lament at her son going away to exile, too, is expressed in a language that could only have emerged from the beating heart of Hindustan: Kis tarah ban mein ankhon ke taare ko bhej duun/Jogi bana ke raj-dulare ko bhej duun (How can I send the light of my eyes to the forest/How can I turn my prince into a mendicant and send him away?).

Versions of the Ramayana in Urdu — in prose and poetry, and as transliterations, transcreations and translations — have been appearing since Urdu gained popularity several centuries ago. According to a comprehensive study of Ram kathan in Urdu by the late Ali Jawad Zaidi, there were over 300 such versions, many from the Awadh region alone, and several written in the style of marsiya-goi popularised by Anees and Dabeer. The earliest Urdu translation of the Ramayana, by Munshi Jagannath Lal Khushtar, was published by the Nawal Kishore Press in 1860. Beginning with ‘Bismillah ir Rehman ir Rahim’, the Khushtar Ramayana, as it came to be called, presents an ankhon dekha haal (an eye-witness account), albeit in a florid style. The Khushtar Ramayana was followed by Amar Kahani by Jogeshwar Nath ‘Betab’ Bareilvi and scores of other versions, often known by their author’s name such as Ulfat ki Ramayana or Rahmat ki Ramayana. Betab Bareilvi’s version, marked by much local colour from the Ganga-Jamuni belt, carries the following description of the ‘shakti baan’: Reh reh ke de rehe thhe duhaii huzur ki/Kham ho gayi thii jung mein gardan guroor kii (At every step they were pleading for mercy from the master/ The neck of pride had been bowed in this battle).

In his name: A Sample of Urdu Ramayana.The remarkably named Hakim Vicerai Wahmi, in his Ramayan Manzum, writes: Ram ne Sugreev ko aage baitha kar yun kaha/Bharat se badh kar tumhe main chahta hun bhai jan (Ram bade Sugreev sit down in front of him and said/I love you more dearly than Bharat, my brother dear).

In his name: A Sample of Urdu Ramayana.The remarkably named Hakim Vicerai Wahmi, in his Ramayan Manzum, writes: Ram ne Sugreev ko aage baitha kar yun kaha/Bharat se badh kar tumhe main chahta hun bhai jan (Ram bade Sugreev sit down in front of him and said/I love you more dearly than Bharat, my brother dear).

Then there’s the incredible Yak-Qafiya Ramayan by Ufaq, published in 1914, maintaining one rhyme scheme throughout, with every verse ending in noon (the ‘n’ sound): Jab khumar aluda dekhi chashm-e mehv-e aasman/ Ram ne bheji barai jung fauj-e jaanistan (When he saw the sky become tinged with pink/Ram sent his army of warriors to engage in battle).

An entire play written in Urdu called Ram Natak, also by Ufuq, with detailed stage instructions, has lyrical rhyming dialogue: Ajodha ko maatam sara kar diya/Bharat ko qadam se juda kar diya (And Ayodhya was plunged into mourning/As Bharat was separated from (Ram’s) feet).

There is also a great deal of scattered Urdu poetry, either specifically on the charismatic figure of Ram or inspired by incidents from the Ramayana, the most famous being the long poem on Ram by Iqbal: Labrez hai sharab-e-haqiqat se jaam-e-hind/Sab falsafi hain khitta-e-maghrib ke Ram-e-hind…/Hai Ram ke vujood pe Hindostan ko naaz/Ahl-e-nazar samajhte hain is ko imam-e-Hind…/Talvar ka dhani thha shujaat mein fard thha/Pakeezgi mein josh-e-mohabbat mein fard thha (The goblet of Hind is brimful with the wine of truth/All the philosophers acknowledge him as Ram of Hind/All of Hindustan is proud of the existence of Ram/The visionaries among them see him as the Imam of Hind/He was an expert swordsman and unique among the brave/And matchless in his piety and passion for love).

Then there’s Zafar Ali Khan declaring: Naqsh-e tehzeeb-e hunood ab bhi numaya hain agar/To woh Sita se hain, Lachman se hain aur Ram se hain (If there are still any visible signs of the culture of Hinduism/Then they are because of Sita, Lakshman and Ram).

And this by Saghar Nizami: Jis ka dil thha ek shama-e taaq-e aiwan-e hayat/Rooh jis ki aaftab-e subha-e irfan-e hayat../Zindagi ki rooh thha, rohaniyat ki shaan thha/Woh mujassim roop mein insaan ke irfaan thha (He whose heart was like a candle in the niche of life/Whose spirit was like the morning sun seeking knowledge of life/ He was the spirit of life, the pride of spirituality/In the shape of a human he was knowledge incarnate).

With Urdu gradually freeing itself from its “Muslim” tag and reclaiming its rightful place as a people’s language, perhaps, it is time to revisit these manzum Ramayanas and, perchance, stage a Ramlila on Ufuq’s Ram Natak. Written by both Muslim poets and non-Muslims at a time when inclusion and pluralism was the norm rather than the exception, they need to be revived and re-read, not merely for their evocations of communal harmony and goodwill, but also because many contain some fine poetry.http://indianexpress.com/article/lifestyle/art-and-culture/the-ballad-of-ram-e-hind-revisiting-the-urdu-versions-of-ramayana-that-once-lit-up-the-stage-4858217/

September 27, 2017 at 5:19 pm

The language of urdu is not confined to certain sect or religion and so, it is enjoyed by all people in the country

December 1, 2022 at 9:36 pm

Very good.

I was looking for Ram Natak by Ufuq in Urdu.

Thanks,

Zafar ibrahim