The families of the Muslim youth from Hashimpura who were shot dead 28 years ago had some committed supporters in their long struggle for justice, reports Jyoti Punwani.

Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

Special to Rediff.com.

EARLIER IN THE SERIES:

- In Meerut, no cry of justice for Hashimpura victims

- ‘To wait for justice for 28 years, and to see them walk away…’

- Hashimpura killings: The trial to nowhere

From the night of May 22, 1987, when 40, 45 Muslim men from Hashimpura, Meerut, were taken away by the Provincial Armed Constabulary, shot and thrown into two nallahs, till March 21, 2015, when the accused PAC men were acquitted, only a few have stood by the families of Hashimpura.

But were it not for these individuals, the trial might never have begun; or, it might still be going on; or, the court would not have even acknowledged that such an incident took place.

V N Rai

The first of these was V N Rai. Then superintendent of police of Ghaziabad, where the two murder sites were situated, he was informed of the incident that night itself.

The first of these was V N Rai. Then superintendent of police of Ghaziabad, where the two murder sites were situated, he was informed of the incident that night itself.

Rushing to the site, he rescued one survivor, Babudin, and ensured that he filed a First Information Report. He also instructed Inspector V B Singh to start the investigation.

Rai had asked then district magistrate Nasim Zaidi (who will take over as India’s Chief Election Commissioner on April 19), his assistant superintendent of police and a few officers to accompany him to the site.

Having heard the entire story, and seen evidence in the form of blood-soaked bodies lying in and around the nallah, Rai went to the 41st PAC Battalion HQ, and also to its motor transport section, to trace the men who had done this, and the truck in which Hashimpura’s men had been taken away, inside which, according to Babudin, the shooting had taken place.

Rai saw a small pool of reddish water in the motor transport section, leading to the suspicion that a blood-stained vehicle had been washed. He instructed Inspector V B Singh to take samples of the water.

But Singh had so much else to do in the investigation of the case over the next few days that he did not take the samples, for which the Crime Branch-Criminal Investigation Department recommended disciplinary action against him. Singh retired without ever being promoted.

Rai recounts that even as he was calling up senior police officers in Meerut to inform them of what had happened, he was told then chief minister Veer Bahadur Singh was passing through Ghaziabad. He decided he must inform the CM of the incident.

However, Rai had not rushed to the crime spot alone. While he left to inform the CM, he could have, say the victims’ lawyers, left his assistant SP and other officers in charge at the PAC Battalion headquarters, to guard it as a crime scene.

The investigation was handed over to the CB-CID on the 24th. Rai had both the FIRs registered by two survivors with him. He had 36 hours to ensure the statements of the PAC men were recorded and the evidence seized, point out the lawyers.

Rai says he was determined to have the perpetrators arrested. However, the memory of the PAC mutiny in 1973, which had led to a bloody confrontation between the rebels and the Indian Army, made him hesitate.

“Snatching the PAC men from their very own den would not have been easy that night,” says Rai. “I thought the DM could call the army to surround the PAC Battalion HQ while we had them identified and arrested.”

By then, news of the CM’s arrival reached him. He found that neither the CM nor any of the senior officers present at the meeting held that night itself, including the state’s police chief, were interested in arresting the perpetrators.

Had it not been for his insistence that Babudin’s statement be taken and an FIR registered, the trial could never have taken place, says Rai. He was also responsible for leaking the details to the press a few days later, he claims. The massacre became national and international news.

He kept track of the lackadaisical investigation, Rai says, and had to insist that his statement be taken.

Now retired, Rai has almost completed a book on the incident. He has also kept in touch with the victims, arranging for the education of the daughter of one of them at the Mahatma Gandhi Hindi University, Wardha (where he was vice-chancellor between 2008 and 2014).

Maulana Yamin

“This frail old man, with a bagful of documents, would be present at every hearing,” recalls Vrinda Grover, advocate for the victims. “Any document you needed, he would fish it out of the bag for you.”

The locks to the Babri Masjid had been opened in 1986, and Maulana Yamin had by 1987 become an active member of the Babri Masjid Action Committee. After the riots, the maulana founded the Hashimpura Legal Advisory Committee to help the victims in their legal fight.

He persisted with the case all through the tortuous years in Ghaziabad where nothing happened, right until the case reached Delhi. He kept it alive, says Grover.

In 1991, his son Tariq Arshad was killed in one of Meerut’s many communal clashes. Ironically, the killers were Muslims. Tariq intervened to help a Hindu rickshaw-wallah who was being harassed by some Muslims. Incensed, the mob turned on him.

“Tariq was my best friend; we shared the same birthday,” recalls Suryakant Dwivedi, editor, Hindustan. A communal harmony award was set up in his name, but given only once, because the maulana’s BMAC activities were not approved of by the government.

A road was also to be named after him, recalls the maulana’s youngest son advocate Junaid, who has been part of the victims’ legal team.

Maulana Yamin died in 2007, 20 years after the Hashimpura incident, soon after the trial started in Delhi.

Harpal Singh

Harpal Singh

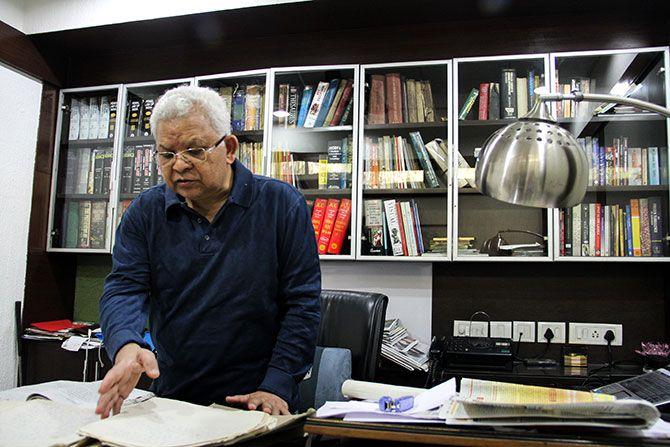

Co-founder of the Hashimpura Legal Advisory Committee, Professor Harpal Singh’s story is cited in Meerut even today in tones of awe.

He is the father who set aside his grief over the terrible killing of his only son, to work for Muslims though his son had been killed by Muslims.

It was during Meerut’s 1987 riots that Dr Prabhat, an anaesthetist who had just started his practice, was dragged out of his car and shot dead. His car was then set on fire with the oxygen cylinders he was carrying — he never would take them out when he came home, as he would be too tired, recounts Professor Singh.

The doctor’s body was flung inside the burning car. His father recalls finding almost nothing of his 32-year-old son when he reached the spot.

“Babuji, I knew nothing about what my son was up to,” the professor recalls being told tearfully by the killer’s father.

“There was no point pursuing the case; no eyewitness would have come forward. The killer was a criminal,” says Professor Singh.

When he was murdered, Dr Prabhat was attending a call from a Muslim patient. Meerut was on fire, but the doctor was probably confident that his father’s reputation in the small town, as a member of the Communist Party of India, and a secular friend of Muslims, would save him from the mobs.

The incident didn’t change the professor’s secular beliefs. In fact, he told his son’s killer in the lock-up: ‘No Muslim can do such a thing during Ramzan. You may wear the clothes of a Muslim, you may look like a Muslim, but you can’t be one.’

After the riots, he joined the Hashimpura Legal Advisory Committee, donating for the victims’ legal expenses, drafting letters in English for them. He accompanied them to the National Minorities Commission office in Delhi when Hamid Ansari. now India’s vice-president, was the chairman, only to be rudely turned away by the NCM staff. His widowed daughter-in-law too would attend the committee’s meetings.

‘Maulana Yamin and Professor Harpal Singh had the moral authority that a committee like this needed,” remarks Vrinda Grover, one of the few who remains in contact with the professor. “Both had lost their sons in communal violence; they shared a deep bond,” recalls the maulana’s son Junaid.

Now in his 80s, Professor Singh, who taught political science at the NAS college (“I’ve taught Marx and Lenin for 30 years, I know more Marxism than the CPI and CPI-M”), remains a living legend in Meerut.

The professor doesn’t talk about his son easily. He would rather discuss the state of the Congress or Delhi’s deadly smog. Interspersed with his comments on these come reminiscences of his son.

The professor was the University topper in MSc biology, but describes his son as being “more intelligent than me; he inherited his mother’s genes,” citing two instances to prove the observation.

When his wife wanted to change her name to Alka Prabhat, the doctor advised her to stick to her maiden name: Alka Gupta. ‘This is a city of banias; here Gupta will do well for you,’ he told her.

Second, the doctor once mischievously remarked to an acquaintance: ‘I like your wife; she’s beautiful and she earns too!’

“I would never have been able to say such things,” says Profesor Singh, with a wry smile.”Three cheers to him!”

Just before he was killed, Dr Prabhat had celebrated his daughter’s first birthday and his wife’s birthday too. He had seen the new clothes that his wife had given for stitching all strewn on the road, after the Muslim tailor’s shop across the road had been looted.

“Then it was May 19th. He said ‘Good morning’ at 5 am to his father, and there the story ends.”

Syed Shahabuddin

Add to cart

Add to cart

When Zulfikar Naseer, then just 15, fled with the Rs 15 a dying Qamruddin gave him at the nallah where the PAC had shot both and left them for dead, he could not have imagined that he would end up meeting two prominent politicians: Syed Shahabuddin and Chandra Shekhar.

A wounded Naseer made his way to his relative’s home in Delhi, who took him to a lawyer named Nawabuddin Ansari, who led him to Syed Shahabuddin.

The politician was then a leading member of the Babri Masjid Action Committee, and a member of the Janata Party. Shahbuddin took Naseer to Chandra Shekhar, and they persuaded him to address a press conference.

Shahabuddin kept Naseer safe at his house for 10 days, while his daughter, a medical student, nursed his wounds. He then enrolled him at Jamia Milia Islamia, safe from the PAC.

Naseer spent four years there, was taken to meet then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi and is today the spokesperson for the Hashimpura victims.

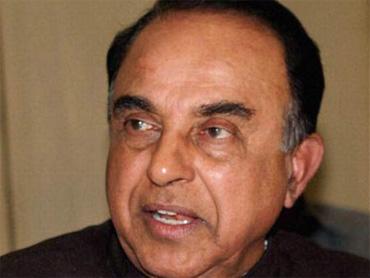

Subramanian Swamy

Subramanian Swamy

The man today identified with the most extreme Hindu voices stood with the Muslim victims of Hashimpura for years. Describing the incident as ‘State-sponsored genocide,’ the then president of the Janata Party led a march of the victims from Ghaziabad to the Boat Club along with Syed Shahabuddin, and sat on a hunger strike asking for an inquiry.

While their trial was on, Swamy filed a petition holding P Chidambaram, as minister of state for home, responsible for the killing of Hashimpura’s Muslims.

The petition spurred the army to send someone to court for the first time; till then, it had refused to cooperate with the prosecution in tracing out the two officers present at the raid.

The petition, which incidentally, describes the PAC in glowing terms, is pending in court.

Rajinder Sachar (PUCL), Iqbal Ansari, and PUDR

A People’s Union for Civil Liberties team led by retired Justice Rajinder Sachar, which included I K Gujral (who later became prime minister), investigated the 1987 riots and brought out a report.

Later, Justice Sachar argued before the Supreme Court for the case to be transferred to Delhi from Ghaziabad.

Iqbal Ansari, founder of the Minorities Council of India, worked hard to get human rights and minority groups to intervene in the Hashimpura case. In August 1999, his article on Hashimpura in his publication Human Rights Today was taken note of by The Times of Indiawhich front-paged the bizarre proceedings of the Ghaziabad court where the case was stuck.

At the same time, at his urging, the National Minorities Commission took up the issue. As a result of this combined pressure, 16 PAC accused surrendered in groups in court in 2000.

Ansari worked closely with Maulana Yamin and the Hashimpura victims till his death in 2009.

The People’s Union for Democratic Rights investigated the Hashimpura massacre immediately after the riots, and filed a petition in the Supreme Court in July 1987, asking that all documents relating to the massacre be produced before the court. It gave the court a list of those ‘missing’ from Hashimpura and asked that the victims be compensated adequately.

In response to the PUDR petition, the Supreme Court enhanced the initial Rs 20,000 compensation announced to Rs 40,000.

In its reply, the Uttar Pradesh government had to acknowledge that nine of the 16 corpses recovered after the incident were part of the PUDR’s list. It also produced in court two reports on the riots.

In 1989, the PUDR brought out a report on the aftermath of the riots, showing how four of the six inquiries set up by the government had been suppressed.

Vrinda Grover

Vrinda Grover

Vrinda Grover was requested by Rajinder Sachar to take up the Hashimpura case after it was transferred to Delhi. She remembers reading the file and knowing it was no good. But the victims were keen to fight.

The victims didn’t know then how lucky they were to get Grover as a lawyer. Any other lawyer would have gone through the motions, knowing the end result.

But Grover, known as a feminist and human rights crusader, was never interested in what she calls the “acquittal-conviction arithmetic. I see that as a zero sum game.”

“There was merit in prosecuting the PAC men, because the prosecution itself would set a precedent. The process would be critical to develop human rights jurisprudence.”

“Today we are in a position, because of this case, to raise larger questions on the functioning of the criminal justice system, the nexus between political parties and the police, the absence of any means of ensuring police accountability.”

“Suggestions on police reform always bank on the assumption that senior officers are better. But this case has shown that there is no self-correcting mechanism within the police; the police leadership and the constable are in a pact. There is a need for both individual culpability and command culpability.”

“Very weak jurisprudence through case law exists on command culpability in custodial deaths. There is not even enough talk about this.”

“The case has told us what has been staring at us in the face: we don’t have an independent investigative agency. The CBI we know is no use.”

“It has also brought out the reality about which we are in denial — the institutional bias against Muslims in the police force.”

“If there is to be a new law for mass crimes, every aspect of the Hashimpura investigation and trial could help fill the gaps in that law. We’ve created the evidence for this. This is a historical opportunity for systemic reform.”

This was Grover’s last trial court case — she now practises exclusively in the Supreme Court.

“The State banks on us getting exhausted,” she says. “But I will never give up a matter. Friends told me this was a dead case. But I was going to persist with it, never mind if it took from 2002 to 2015.”

Grover’s role didn’t end with just appearing in court. Her commitment to the case made her fight for a special public prosecutor, seeing the apathy of the PP assigned to the case; took her to retired police officers from UP for help in comprehending the charge sheet; and made her phone every army unit she could for help in tracing the army officers whose deposition was crucial — in vain.

She also got the victims to file RTI applications asking for details of disciplinary action, reinstatement and the Confidential Reports of each of the 19 accused, making it a total of 613 RTI applications.

Grover also marched with the victims to Lucknow on the 20th anniversary of the incident. The solidarity shown by human rights organisations and the publicity generated, rattled then chief minister Mulayam Singh Yadav enough to give in to two demands: compensation and a special PP.

Today, after the judgment, Grover continues to be the person trusted most by the victims. They inform her every time the administration or political parties approach them. She has advised them that the new Hashimpura Action Committee must be open only to the victims and their families, and it must have at least one woman.

Satish Tamta

Satish Tamta

One of the three names recommended by the victims as special public prosecutor, Satish Tamta was appointed by the UP government in 2007 on a fee of Rs 11,000, and stopped being paid two years later.

Repeated letters to the UP chief secretary went unanswered or even came back. “What is the inference you can draw?” he asks.

So why did he keep on with the case?

“Why should the victims suffer?” asks Tamta.

It took him two months to read the case papers, recalls Tamta. He would carry the ragged files to hospital, where he was looking after his father.

To make things worse, he got no help at all from the prosecuting agency. Not a single officer of the CB-CID, which had investigated the case, turned up in court. He had to discuss the case with the inspector general of police in Lucknow by phone.

The victims got the handwritten case diaries typed out; and Tamta at his own expense got all the yellowing, tattered documents xeroxed.

Even the minimum courtesies were not observed by the CB-CID. When Tamta asked that the first investigating officer in the case to be summoned, he found the man at his doorstep at 6 am on the very day of his deposition. “The CB-CID knew he was an important witness and the case was more than 20 years old. They should have sent him the summons in time for him to have reached Delhi a day earlier, so that he could prepare for his testimony.”

Given the quality of evidence, Tamta was not optimistic about the outcome. “The public prosecutor is a neutral person, like the judge. I have to go by whatever the investigating agency has done. How can I manufacture what doesn’t exist? That’s not my job.”

Yet, he is unhappy with the judgment.

“Given the circumstances, what emerged during the trial was enough to establish this was the truck, this was the driver, and one accused, Leeladhar, was there. Yet, they were all acquitted. The Supreme Court has observed that faulty investigation should not become an advantage to the accused. But here it did.”

Photographs of V N Rai, Harpal Singh, Vrinda Grover and Satish Tamta: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

http://www.rediff.com/news/special/the-good-samaritans-of-hashimpura/20150414.htm

Leave a Reply