By Jeffrey R. Young, Washington, Jan 18,2012

A professor lost his long legal fight to keep thousands of foreign musical scores, books, and other copyrighted works in the public domain when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against him on Wednesday in a case that will affect scholars and artists around the country.

The scholar is Lawrence Golan, a music professor and conductor at the University of Denver. He argued that the U.S. Congress did not have the legal authority to remove works from the public domain. It did so in 1994, when the Congress changed U.S. copyright law to conform with an international copyright agreement. The new law reapplied copyright to millions of works that had long been free for anyone to use without permission.

The Supreme Court heard the case, Golan v. Holder, No. 10-545, last October, and in a 6-to-2 ruling on Wednesday, the justices upheld the changes in U.S. copyright law.

“Neither the Copyright and Patent Clause nor the First Amendment, we hold, makes the public domain, in any and all cases, a territory that works may never exit,” declared the majority opinion, which was written by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

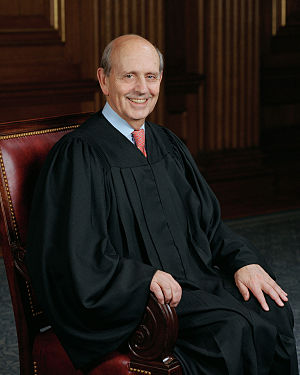

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Stephen G. Breyer, writing for himself and Justice Samuel A. Alito, faulted the Congressional action. “The fact that, by withdrawing material from the public domain, the statute inhibits an important pre-existing flow of information is sufficient, when combined with the other features of the statute that I have discussed, to convince me that the Copyright Clause, interpreted in the light of the First Amendment, does not authorize Congress to enact this statute,” he wrote.

End of the Fight

Mr. Golan’s lawyer criticized the ruling. “Obviously this is disappointing,” said the lawyer, Anthony Falzone, in an interview. He said the decision would greatly increase the number of symphonies that the professor, and artists around the country, “are now for all intents and purposes unable to perform and record because the [permissions] fee makes it infeasible.”

Mr. Golan had argued that taking works back out of the public domain would hinder creativity by making artists more cautious about remixing or otherwise using works, fearing their status could change in the future in a way that required payment to copyright holders. More broadly, academics have expressed concern that upholding the 1994 law would make it much more difficult to write books or assemble course readings without having to deal with a host of legal hurdles—or just prohibitively expensive fees—to avoid violating copyrights.

In the majority opinion, the justices noted that the restrictions of copyright law can sometimes help creativity, though, by devising a system that allows authors to collect payment when their work is used. “Congress had reason to believe that a well-functioning international copyright system would encourage the dissemination of existing and future works,” Justice Ginsberg wrote.

This marks the end of Mr. Golan’s fight, according to his lawyer, as the only remedy now would be a change in U.S. law.

“It would be highly unlikely,” said Mr. Falzone, “that Congress would amend the statute in a way that would vindicate the interests of my client and the public.”

‘A Grant of Sweeping Authority’

But the ruling could open the door for Congress to craft further changes in copyright law that scholars might consider even more restrictive, said Kenneth D. Crews, director of the copyright-advisory office at the Columbia University Libraries.

“It is a grant of sweeping authority to Congress to shape copyright law in almost any way that it chooses,” he said of the decision. “This should raise a red flag to be watchful about other developments in congress like SOPA,” he added, referring to the Stop Online Piracy Act (HR 3261).

That bill, which is under consideration in the U.S. House of Representatives, and a related measure in the Senate sparked an online protest on Wednesday. Several major sources of free information, including Wikipedia, blocked access to their content temporarily and put up pages asking users to help fight against the legislation. The all-black home page on Wikipedia started with the headline “Imagine a world without free knowledge.”

Copyright holders and other owners of content, meanwhile, applauded the ruling.

The Motion Picture Association of America, for instance, issued a statement saying that it is “pleased that the Supreme Court has again ruled that strong copyright protection is the ‘engine of free expression’ and fully consistent with the First Amendment.”

Related articles

- Supreme Court Says Congress May Re-Copyright Public Domain Works (wired.com)

- Supreme Court Affirms Broad Congressional Authority to Offer Intellectual Property Rights for Public Domain Works (patentlyo.com)

- Supreme Court to Decide if Classics Remain in Public Domain (ibtimes.com)

- Supreme Court hears important public domain case: Can Congress remove works from the public domain? (teleread.com)

Leave a Reply