Mumbai:

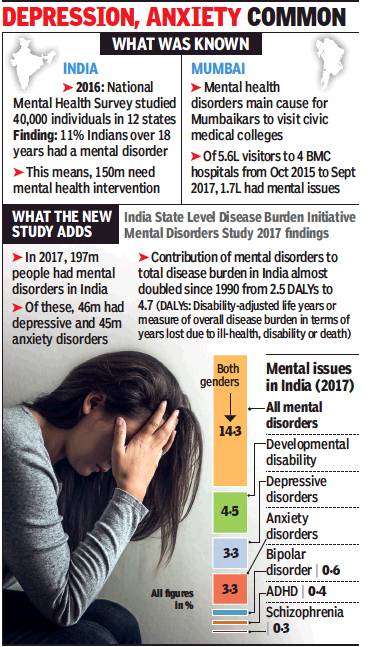

Around 200 million or 20 crore Indians—almost the population of Pakistan or Brazil—were affected by mental disorders in 2017. This includes 46 million or 4.6 crore Indians suffering from depression and another 45 million or 4.5 crore from anxiety attacks.

These are the findings of a new study—India State-Level Disease Burden Initiative Mental Disorders Collaborators—published in medical journal The Lancet Psychiatry on Monday. The study estimated the contribution of mental disorders to the total disease burden in India almost doubled from 1990 to 2017.

“The big message here is that mental health cannot be ignored in India,” said one of the study’s authors Dr Rakhi Dandona from the Public Health Foundation of India. “We always knew that mental health is a problem but this study tells us how much of a problem it really is. One in every seven Indians has a mental disorder and these 200 million affected Indians deserve attention,” she added.

The study, which also looked at the state-wise prevalence of mental disorders, found that southern states, including Maharashtra, have a higher prevalence of depression. More Indian women (3.7%) than men (2.7%) have depression, which also affects the elderly in higher numbers. Maharashtra has the highest prevalence of attention-deficit hyperactive disorder.

The study found a regional divide in the prevalence of depression and related suicides. “There is a higher prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders in southern India states, which also had higher suicide rates than northern India states,” said Rahul Shidhaye of Pravara Institute of Medical Sciences, Loni.

The reason for the high level of mental disorders, said experts, are societal pressure and a rising sense of alienation or loneliness. Psychiatrist Dr Harish Shetty said the country is in a “chronic disaster” state. “There is high level of anxiety as well as hyper vigilance brought on by violence and a volatile political climate over the past 15 years.”

Experts said there is an urgent need for India to draw up regional level mental health intervention plans. “The real question is what are we doing about these figures. A headcount doesn’t make sense unless we come up with an action plan,” said Dr Soumitra Pathare of Pune-based Centre for Mental Health Law and Policy.

Around 200 million represents a sizeable vote bank. “If we consider each mentally ill person affects their family made up of three other members, then at least 700-800 million people in India are affected by it. This is almost the population of Europe. We need more money in mental health,” he said.

Leave a Reply