In the business of media, employees often have to sign contracts with manipulative or severe clauses.By Prateek Goyal

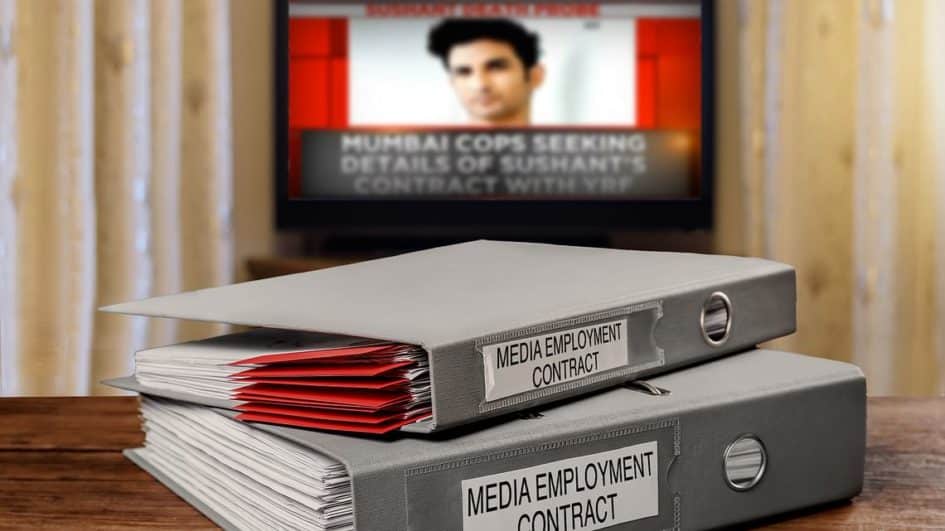

At the centre of the media circus over Sushant Singh Rajput’s death last month is a controversy over a contract signed by the Bollywood actor with Yash Raj Films. Rajput reportedly signed a three-movie deal with the production house, and the payments hinged on whether the movie was a “flop” or a “hit”. The Bandra police, which is investigating Rajput’s death, acquired a copy of the contract on June 29.

Media houses seized the story as details of the contract emerged. Actor Kangana Ranaut waded into the frenzy to call Bollywood a “ruthless place”. TV news channels like Republic reported on “Bollywood controversies” such as how contracts “ bind” actors “to not work on other projects even if they like them”.

And yet, the business of Bollywood contracts is not very different from the contracts that employees sign with media houses. Clauses in these media contracts range from how a company can “deduct any sum as may be recoverable from an employee” to the usual business of non-compete clauses.

It should be noted that non-compete clauses in India are, by and large, not enforceable, except for some exceptions. Yet this doesn’t stop media houses from inserting them into their boilerplate employee contracts.

Here’s a quick run-down of some clauses and contracts offered by media houses in India.

Republic TV might have lashed out at Bollywood for its non-compete clauses, but the channel still includes them in its own employee contracts.

“From the date of execution of the agreement and for a period of six months after its termination or expiry of this agreement, the employee shall ensure that s/he shall not directly or indirectly in any manner whatsoever, whether for profits or otherwise carry on , or be engaged, employed, concerned or interested in any business which is the same as or to competes with the business being carried on by the company.”

In short: An employee can’t work with an organisation engaged in the “same business” as Republic for a period of six months after leaving.

Like most other companies, a Republic employment contract can be terminated by either the company or the employee by giving 60 days’ notice in writing, or payment in lieu of notice. However, the payment in lieu of notice at Republic is calculated on the basic salary, not the full salary.

The company’s contract also states that it’s entitled to “deduct any sum as may be recoverable from the employee from time to time as per company policies”. In other words, if an employee owes any money under any company policy, it can be deducted from the employee’s salary. This is also a standard clause in most contracts.

Additionally, Republic’s incentives to its employees are based on these very same ratings. For example, a senior employee will receive an annual incentive of Rs 3 lakh if the channel is at number one for 52 weeks. The annual incentive is Rs 2.5 lakh if the channel is at number one for 50 weeks, Rs 2 lakh for 48 weeks, and no incentive for less than 48 weeks.

The TV division of Bennett Coleman and Co. Ltd also has a non-compete clause in its contracts: an employee, after leaving, cannot work in “television, publishing, telecom, radio, internet, magazine, multimedia company or news media engaged in similar services for at least a period of one year” without BCCL’s written consent. The clause includes taking up assignments or projects with a “competing business of a similar genre or nature” as the job the employee performed at BCCL.

The contract adds that BCCL has the authority to take “legal action” if the non-compete clause isn’t followed.

A senior journalist, who has signed two contracts like this in the past, told Newslaundry that the clause violates press freedom. “It’s a violation of a person’s right to livelihood. It’s deplorable when such clauses are used in the TV news industry,” the journalist said. “The very industry that has an opinion on everything and everyone — it’s so shallow within. These clauses are used to threaten journalists, coerce them into working under duress, and strip them off a future in journalism.”

Another controversial clause that the Times Group includes in its contracts pertains to an employee’s use of social media. The clause states that the intellectual property rights of all social media posts by an employee belongs to the company. In the event of the company allowing the posting of work or material in any media, including social media, all posts by the employee must be made under a name or acronym that contains the company’s trademark, or a mark permitted by the company.

The Times Group was called out in 2014, and again in 2017, for its social media policy. A Times of India employee, on the condition of anonymity, told Newslaundry: “In TOI, everyone has to post a minimum of two tweets a day from the account made by the company. One cannot post independent content through these accounts…In order to post independent content, employees have created separate accounts.”

According to its employee contract, if Hindustan Times terminates an employee’s services before the completion of their fixed term engagement period, the company is not liable to pay the salary for the months remaining in the fixed term period. Instead, it will only pay two months’ salary.

A fixed term engagement period is when an employee is hired for a specific period of time.

A former employee of Hindustan Times spoke to Newslaundry on the condition of anonymity. “Many HT employees were asked to leave during the Covid layoffs,” the employee said. “They were given just two months’ salary, despite having six or seven months left in their fixed term engagement period. They induct manipulative clauses in the contracts and take advantage of them.”

‘If you scratch the surface, the media is completely feudal’

Vishwa Deepak, an independent journalist who quit Zee News after the channel’s coverage of Jawaharlal Nehru University and Kanhaiya Kumar in 2016, told Newslaundry that such contracts are a result of “the semi-feudal structure and colonial pattern of the media in India”.

“The people in charge think of themselves as unquestionable,” Deepak said. “Besides, there are no unions anymore and the ones that exist work only for their own interests. A journalists’ union is important to counter such unfair practices.”

Geeta Seshu, an independent journalist based in Mumbai, said the contracts are “illegal”. “They do not follow any of the norms laid down under the Working Journalists (Conditions of Service) and Miscellaneous Provisions Act, 1955,” she pointed out.

She added: “Non-compete and other such clauses are complete nonsense. They are the product of the so-called neo-liberal corporatisation of the media. It is ‘so-called’ because if you scratch a little of the surface, it’s completely feudal.”

Seshu also cited the recent layoffs in the media, saying, “The manner in which the media has dealt with scores of journalists is utterly shocking and disgusting….They treated them in the most feudal take-it-or-leave-it kind of an approach.”

”The clauses, such as non-compete, are unconstitutional,” said MJ Pandey, a senior journalist and a member of the Brihanmumbai Union of Journalists. “How can a person be denied the right to work, which is a fundamental right? A journalist who has worked in broadcast media will get the job in media only and not in a mine. These clauses attack the right of livelihood of a journalist.”

Given that “thousands of factories churn out journalists” every year, Pandey said, there is ample supply. “In such a situation, it’s almost impossible for people to go ahead and challenge their contracts,” he said. “They think they will be targeted if they do so and might not get a job anywhere…The contract system was started in the print media by BCCL and then followed by others.”

A human resource manager with a leading English daily told Newslaundry, on the condition of anonymity, “These contracts are definitely one-sided and manipulative but they are made to stop the talent from joining competitors. Decision-making authorities try to grab talent from their competitors by paying them a higher salary. So in order to counter it, clauses such as non-competitive or anti-poaching are introduced. And this is done not only in the media industry but everywhere.”

Senior journalist P Sainath, who is the founder-editor of the People’s Archive of Rural India, said, “I have always said that the whole contract system is dubious. It has not been tested in court… For instance, no one can enter into a contract, of free will or otherwise, with an employer to be her/his slave because such slavery is unconstitutional.”

He said that the contracts, beginning with the mid-1980s, “destroyed” journalists’ unions and the independence of journalists.

“The death of unions has been engineered using the contracts as a weapon. Members of journalists unions were told by the employers that if they are going to stay in the union, then they were not going to make any progress in the organisation, and they were told their contracts would not be renewed.,” Sainath explained. “That’s how they undermined the unions…”

He added: “Basically these contracts allowed the companies to use, manipulate, torment, and coerce journalists to participate in corrupt practices like paid news. The coming of the contracts and the destruction of the wage of the Working Journalists Act led to the collapse of journalism, the loss of independence and freedom of the journalist. It began the severe erosion of everything about Indian journalism — from content to context to integrity and security of journalists…”

This is echoed by Jaideep Hardikar, a Nagpur-based journalist, writer and researcher who has worked with various news organisations.

“The contracts are a consequence of neoliberal policies and the steady weakening of the working journalists’ trade unions,” he said. “The promise was to improve productivity and quality, but over a period the system turned into hire and fire business, because the contracts were a one-sided affair; they made this an employer-friendly market. Problem is these contracts are not journalist or journalism-friendly.”

Hardikar said that trust has evaporated between reporters and editors, and jobs and wages are not a certainty today. “Reporters have turned into vendors, selling content, often whose veracity and credibility is on them and not the media outlets or editors who curate that content,” he said. “Basically there is no such thing as a contract. Because a contract is between two parties, but over here everything is one-sided in the favour of the media owners. Contractual system in the media eventually brought down the standards and ethics of journalism. And the terms such as loyalty to readers and editorial integrity have gone for a toss.”

courtesy Newslaundry

Leave a Reply