Memory loss, extensive brain damage and internal bleeding. For the first time, the author and human rights activist shares what happened when he admitted himself to a general ward of a premiere public hospital after he got Covid-19 in October.

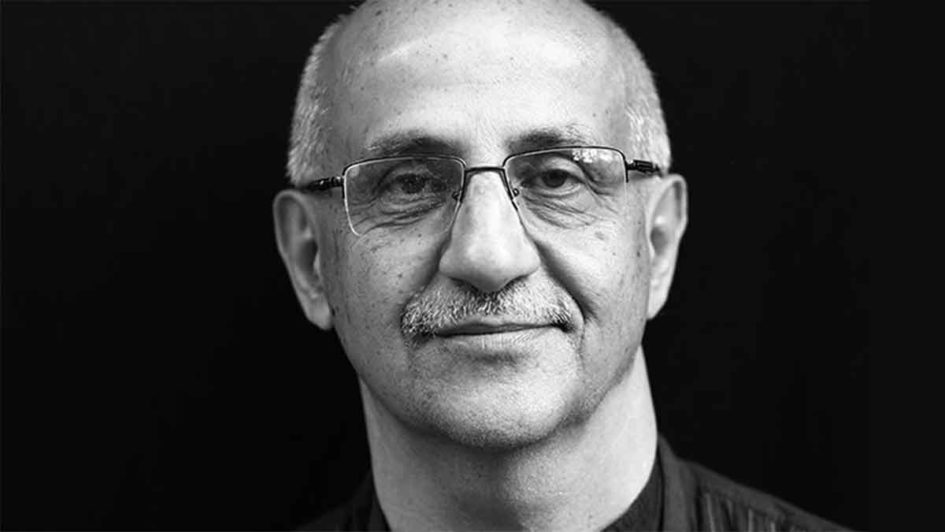

NATASHA BADHWAR

New Delhi: “The government has declared war against its working poor. The response of the state to the pandemic counts as a crime against humanity, indeed several crimes, and I am saying this very carefully and advisedly.”

Within days of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement of a country wide lockdown on 24 March 2020, Harsh Mander found himself leading teams of social workers and volunteers as they banded together to distribute food and extend emergency relief to the suddenly stranded working poor of India.

As strictlockdown was enforced across the country, millions struggled to cope with an overnight catastrophe with no work, wages, mobility and food to sustain themselves. Overwhelmed by hunger, helplessness and dread of the disease, migrant workers began to walk hundreds of kilometres to their home districts, despite the constant threat of police violence and detention.

“It was apparent that while some lives were to be protected, others were dispensable,” writes Mander in his new book, Locking Down The Poor, which will be released by Speaking Tiger Books on 23 December. Mander, who works with survivors of mass violence and hunger, homeless persons and street children is the director of the Centre for Equity Studies, a research organisation based in New Delhi, and and helped found Karwan e Mohabbat, a campaign for radical love, solidarity and atonement for the rising deluge of hate lynching. He has also served as Special Commissioner to the Supreme Court of India in the Right to Food Campaign.

Speaking to Natasha Badhwar for Article 14, Mander opens up for the first time about his own near-death experience of being a Covid patient in a public hospital and the implications of being in the midst of a humanitarian catastrophe. Edited excerpts of the interview:

You are still recovering from the complications that you had to endure during your hospitalization after testing positive for Covid-19. Tell us what you experienced when you chose to get admitted in a general ward in a prestigious public hospital in Delhi.

A: Because I was with my young colleagues on the streets from the second or the third day when we were distributing food, I was expecting that I would catch Covid very early. Despite its inevitability, I took all precautions. My father was 95 and I explained to him that I was going to stop seeing him. I knew our short meetings almost every day that I was in Delhi, was a slender string that held him to the world. I told him that every evening we would speak on a video call instead. My mother-in-law stays with us; she is 85 and uses a wheelchair. I told her that I would not enter her room. My wife and I started sleeping in separate bedrooms. But I didn’t get Covid when I most expected it during the lockdown months.

In October, I spent four hours in a Covid clinic we had started for the homeless with Médecins Sans Frontières and we had found very alarming levels of positivity among the homeless—more than 15%. Within a week some of my colleagues, my family and I tested positive for Covid. We hired a trained nurse to monitor my 85-year-old mother-in-law’s symptoms at home. My wife had mild fever. I have a congenital heart problem. Finally I decided to accept the advice of some very dear doctor friends to admit myself in a hospital. I did not want to burden my family in case of complications. In retrospect, it seems like not a wise decision.

I requested that I be admitted to a general ward of a premiere public hospital, not a private room; and what I experienced there is as close to hell that I can imagine. I’m not exaggerating.

There were about 50 other Covid patients in the ward. Nobody gave me a change of clothes. At home, people had been checking my oxygen regularly. Here nobody even talked to me. No one attended to any patient. The noise levels were so high, one could not rest. Nurses and ward boys were screaming across the ward at each other and patients. Then there were these monitors that beeped all the time. The monitor next to my bed was not functional but it continued to beep. Nobody would allow you even to go to the toilet. You had to keep begging, saying I’m desperate.

I spoke to the ward boys and found out that most of them were untrained. They were new recruits who had lost other jobs, such as room boys in hotels which had closed down during the lockdown. Many from the hospital staff refused to serve in a covid ward. These young men had applied to work in a Covid ward because of financial desperation. Among the patients, a few were convinced that they were going to die and they were in a panicked state. Nobody was allowed any visitors, so they were wailing about dying and crying for their family.

There was total chaos and pandemonium. Luckily nobody died, otherwise there would have been corpses in the ward too, something working poor and homeless people had told me they had had to endure. After two days, I begged them to let me have a bath at least, I can’t be just lying in these same clothes. Very reluctantly they let me go. And after that I’ve lost memory of what happened for 10 days. I have complete amnesia.

My family tells me that I suddenly stopped answering the phone. My wife got very anxious and when she asked what had happened to me, she was told that I had gone into depression. She was not convinced, of course. She said this is not in his nature but even if he has, one doesn’t just switch on and off. He was talking to me at great length a day ago and now you’re saying he is not even speaking a word? It doesn’t work that way, something must have happened. But the doctors insisted, inexplicably, that I had gone into deep depression.

Somehow my wife managed to get me discharged and bring me home. I have no memory at all of those days. After I came home, I couldn’t eat, I didn’t speak and I had a continuous splitting headache. I recalled the names of my wife and daughter but when they asked me who they were, it seems I said they were nurses. After a few days, friends and family took me to another private hospital where the doctors examined me and said, “There is no problem with regards to Covid, but he has a very serious head injury.” My MRI scans showed extensive brain damage and internal bleeding.

Despite the fact that I was sinking and needed emergency care, they were unable to keep me because I was Covid positive. I was taken to a third hospital that had a dedicated Covid ward. Again I had to be cut off from my family. I remember my memory slowly returning. First there were hallucinations. I felt I was in Assam among those released from the detention centres; they offered me love and solace because I had survived Covid. Eventually I came home and my memory began to recover–slowly but steadily.

Even now when senior doctors look at my MRI, they ask, “How are you even alive?” If my family had not intervened in time, I would have been just one more Covid death. But it was appalling and shocking medical negligence, not Covid that nearly killed me.

This has happened to me despite all the social capital that I have–the friends, education, goodwill. What kind of criminal callousness would ordinary Indians be experiencing?

You write in your book that the Indian state chose to abandon its poor and marginalised, even as it destroyed their livelihoods and pushed them to the brink of starvation. What other option did the Indian government have in the face of a pandemic, other than a lockdown?

A: It is simply not true that the government did its best and that it is a virus that is the cause of the suffering people have endured.

Firstly, why did we need a lockdown? Should it have been as severe, extensive and long? In his first speech, our Prime Minister asked us to follow these norms–stay at home, wear a mask, maintain social distance and keep washing one’s hands.

Even while he was speaking, I was thinking, has our Prime Minister forgotten that the large majority of Indians in cities don’t even have homes, or live in crowded shanties? How and where will they lock themselves down? In cities like Bombay that have some of the densest populations in the world, often 10 people share a single room and 150 people share a toilet. How are they going to distance themselves from each other? The Prime Minister didn’t seem to be at all concerned about the large majority of the Indian poor.

Mander’s new book will be released on 23 December.

He said everyone should keep washing their hands. You just have to go out every morning and see scenes outside slums where people are desperate to buy 2-3 pots of water with which they have to bathe and cook all day. How can we talk about washing hands regularly when there is no running water? When he spoke about banging thalis in balconies, clearly he wasn’t speaking to those people who don’t have balconies.

That was just the starting point. We know that there were only 600 recorded infections when we suddenly locked down the entire country. If people had been assisted to go to their homes in the first week, there would have hardly been any infection in the rural areas. Instead, what did we do? We forced them to stay in extremely crowded settlements and this is a virus that loves closely packed bodies. We actually used the lockdown to create hothouses for super spreading of the disease. Finally when people became desperate and started walking to reach home–there were lakhs of Covid carriers among them. This could have been avoided if the lives of the working poor had been taken into account.

Many relief packages were announced by the central and state governments. How effective have these measures been in sustaining India’s workers through the pandemic?

A: India’s cruel totalitarian lockdown thrust millions into mass hunger and joblessness and came with one of the smallest relief packages in the world. Nine out of ten workers are informal who eat each day what they earn in daily wages. Let me give you an example that illustrates the state’s response to the most vulnerable people. There’s a place called Yamuna Pushta in north Delhi where about 4,000 homeless people have been living on the river bank for years. When Covid began to spread, they were much safer there because they were sleeping in the open and could maintain distance amongst themselves. The state government began to round them up and packed them into school buildings where they had to line up for food and hundreds of them had to share the same toilets. I met men who had climbed trees and hidden inside large pipes to escape being caught. They narrated their experiences to me.

At Yamuna Pushta in north Delhi, daily wage workers lined up for hours to receive food during the lockdown/SANDEEP YADAV, KARWAN-E-MOHABBAT

One of them had fever and after his sample was taken for Covid testing he was sent to a Covid ward. He was told it would take 4 days for the results to come. In those 4 days, he stayed with confirmed Covid patients and he was asked to pick up corpses and do the work that other health staff had refused to do. He escaped after his results came negative and walked in the dead of night to find refuge in an abandoned sewer pipe. The only way these men could protect themselves was by staying away from the state because the state was simply wreaking devastation on them.

Before the lockdown, perhaps there was a mirage of expectations among the millions of our informal workers that the state will protect me and my employers will not abandon me in case of a catastrophe. But that’s precisely what we did to the workers. Besides the mass hunger and vulnerability, there has also been a complete breakdown of trust–in the state, in capital, and in the middle classes.

There is no one for us–is what the labouring poor and the destitute poor have learnt. This is a terrifying reality with which they will live as they rebuild their lives–not with the help of, but despite the state.

One of the rationales we were given for the lockdown was that health infrastructure needed to prepare and build up to deal with the surge of cases that would come once the lockdown was over. To what extent was this justification valid?

A: I wish there was evidence to believe that we used the lockdown, with all of its costs, to build up our medical facilities. Virtually nothing was done. The government talked about adding hundreds and thousands of beds but these were not new beds, these were repurposed beds. Basically our approach was this–for this period of time we don’t care if you have cancer or a cardiac arrest or virtually any other ailment. In Mumbai, they actually took patients out from hospital wards and put them on mats under a flyover in order to free up beds for Covid wards. We have not even measured the impact of this on childbirth and maternity healthcare, and on domestic violence and mental health, and the special impacts on women, children, persons with disability, informal and casual workers, and workers in stigmatized occupations like, say, sex work.

80% of our trained health force, including doctors, work for the private sector. The contribution of the private sector to helping people in this time of crisis has been estimated at not more than 10 percent and that has also benefited only the rich. Even the middle class was treated very badly.

A country like Spain nationalized its private hospitals. We could have chosen to put people first too. But we chose instead to protect the interests of for-profit private health providers, even in the greatest health emergency in a century. No wonder that the union home minister, many chief ministers, union ministers, state health ministers would check themselves into high-end private hospitals when they contracted Covid. The hellish experiences of the public health systems were reserved for the working poor, and for a while even the middle classes were not spared.

It has been said that the pandemic has served as an X-ray: it has exposed to the naked eye everything that was covered and beneath the surface.

A: I believe that when the history of our time is written, this will be seen as amongst the cruellest periods. There has been a total breakdown of solidarity. I have been talking so far about the government as if the problem has been out there, removed from us, but we have to realize that it is much more here with us–with the middle class and rich elites.

When India’s migrant labour began to walk home, it became the biggest distress movement of a population in human history except for the people of Africa being taken across the oceans as slaves to America. The movement of migrant workers in 2020 was bigger than the displacement during India’s partition in 1947. This should have shaken us to our core.

Yet people like us were stunned to see the numbers of migrant workers on the roads, as if we had never seen them before. How did we miss them? Your entire life–from the moment you open your eyes–the person who delivers your milk, your newspapers, the person who is taking care of your children, cooks the food, drives you to work etc.–all of them are migrant workers and you didn’t care about what happened to them?

9 out of 10 workers have no economic protection at all. One would have thought that at least now the government would create a more comprehensive labour protection policy, but instead they have chosen to dismantle even the few labour protections that existed.

But I think that if we go away from this conversation thinking that the government is the problem, we will have completely missed the point. The problem is us. We elected these governments. We have endorsed a Prime Minister who chose, at the peak of the hunger crisis, to be photographed wearing expensive clothes and feeding peacocks in his garden. The symbolism of it is something else. And we applaud this leadership?

The pandemic is an X-ray that has revealed how little we care. The country’s health and welfare systems have collapsed, primarily because of the hubris and inefficiency of a regime obsessed with image management but it was emboldened by not just the apathy of the vast majority–of people like us–but by our spectacular failures of even elementary compassion and solidarity.

Leave a Reply