In Solidarity

Sweta Dash

In early November 2020, Delhi witnessed its highest number of daily COVID-19 cases, prompting the Chief Minister to declare it the third wave. A Hindu festival, high levels of pollution and the winter season were seen to compound the effects of the pandemic. Despite a dip in pollution levels post-Diwali, Delhi still reported a daunting 21% of all COVID-19 deaths in the country. The Delhi High Court declared the situation “alarming”, and rapid remedial measures like weekend lockdowns and a new SoP by the Ministry of Home Affairs were brought in.

A clarion call for the farmers’ Dilli Chalo campaign reverberated across the nation amidst this din, and thousands arrived at the borders of the national capital on November 26.

Protests were springing up across the country since September 2020, when the government passed three contentious laws affecting the lives and livelihoods of farmers. Farmers claimed the laws would erode whatever little security mechanisms were accessible to them, catering to big corporations in ways that would leave them exposed to exploitation. Three months later, farmers arrived in large numbers at four Delhi borders – Singhu, Tikri, Ghazipur and Chilla – demanding a repeal of the laws. In February 2021, after more than ten rounds of talks with the government, lakhs of farmers continue to pitch their tents on the roads. The protest has grown larger and so has the paraphernalia around it.

Providing ‘some semblance of security’

On November 27, Dr. Siddhartth Taara, Resident Doctor at Hindu Rao Hospital in Delhi, arrived at the Singhu border anticipating medical emergencies at the protest site. By then, farmers had faced the strong-arm tactics of the state – heavy security deployment, water cannons, and tear gas shells. Carrying a few small packets of medicines with him, Dr. Taara had come alone, unsure of what to expect. “I went from one langar spot to another, asking if anyone needed help,” he said. “I cannot speak Punjabi and I am a shy person, so it was difficult for me to ask for things as basic as a table to set up medicines. The people were kind and, eventually, things fell into place. A proper system is up and running now,” he said.

In the second week of December, Dr. Taara spotted an old man crossing their health camp near a Gurudwara langar. “He was holding a uro-bag. It is used only in the instance of a surgery and/or when the patient is suffering from incontinence,” he explained. Dr. Taara promised the man medical assistance at the health camp when needed.

In a year that has been particularly distressing for healthcare workers because of exposure to the exhausting and threatening work of COVID-19 care, they have had to raise their voice against several denials of their rights – for reasons ranging from salary overdue, non-availability of PPE kits, and most recently against a new rule allowing practitioners of Ayurveda to perform minor surgeries. Inevitably, healthcare workers have also been drawn into the farmers’ protest paraphernalia from the start. They have responded, both from the margins and the thick of things, to the government’s attempts at pushing anti-poor policies against their own community as well as the farmers.’

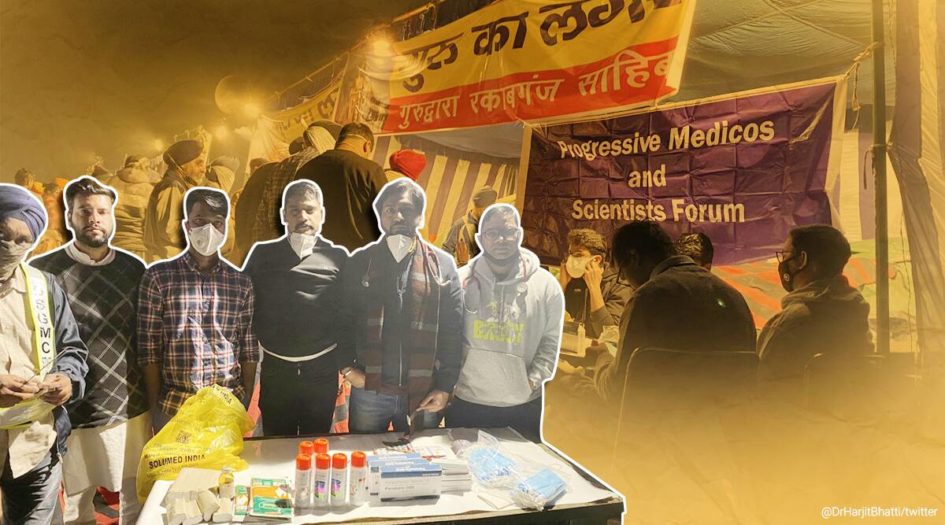

Dr. Harjit Bhatti, doctor at AIIMS-Delhi, and the national president of Progressive Medicos and Scientists Forum – a network of healthcare workers and researchers vocal about social justice – had organised 18 health camps at the farmers’ protest sites by December 20. He joyously shared that over 100 doctors from different hospitals in Delhi had promised to pitch in.

For Dr. Bhatti, standing in solidarity with farmers is an attempt to stand up against the many faces of oppression and injustice. “Sarkaar ko farq nahi padta k desh ka gareeb kaise jiye,” he said. (The government does not care about how the poor live). As an example, he brought up the changes made to the MBBS course fee structure in government medical colleges in Haryana. Introduced to “incentivise doctors to opt for Haryana government medical service”, the change now mandates that students sign an annual bond of Rs. 10 lakh that they can pay off themselves or through an education loan facilitated by the government. “Medical students will now bear an expense of Rs. 40 lakh in a government medical college in Haryana! These are vicious ways of keeping the poor away from this profession.” Dr. Bhatti said.

Ms. Urmila Rulaniya, a nurse at the AIIMS hospital in Delhi, is not unbeknownst to protests. The AIIMS nurses union has protested several times during the pandemic. In December 2020, the union complained about 23 unresolved demands, including reworking the salary structure in accordance with the Sixth Pay Commission. Their call for an “indefinite strike” was cut short in the belief that “the administration would make good on its promises and also because we simply cannot afford to not treat patients,” Ms. Rulaniya explained.

From a family of farmers in Sikri district of Rajasthan, Ms. Rulaniya worked in the fields in the early days of the COVID-19 lockdown. She said minimum support price and the perils of privatisation – two issues the farmers’ protests have highlighted – have been a part of her family’s daily conversations. “We grow wheat, bajra, channa, peanuts, onions, and other crops depending on the season. Some years, we would spend rupees 1.5 lakhs on a crop of onions and the sale price would barely reach rupees 2 lakhs. We wouldn’t even break even with this small margin, forget compensation for our labour. We have had to sell onions for Rs. 2 to Rs. 5 a kilo, while the ideal price should have been Rs. 15 to Rs. 20,” she said.

Ms. Rulaniya is posted on COVID-19 duty at the AIIMS Trauma Centre since graduating in September 2020. She goes to the protest health camps as often as she can. “People at the top have no idea about farmers’ pain. They work hard an entire year for one fasal (crop), and live a life of uncertainties. We can’t change the government overnight, but the least we can do is provide medical help and primary care,” she said.

Echoing the sentiment, Dr. Bhatti said, “We try to give them (protesting farmers) some semblance of security in these difficult times.”

For some like Dr. Mahi Ahluwalia*, motivations to volunteer at health camps are different. “We are public servants, and it is our responsibility to treat patients, whether a protestor or not,” Ms. Ahluwalia said.

Doctors have been relying on medical representatives and pharmacists for a steady supply of medicines at the health camps. Pankaj Kumar, General Secretary of Delhi Sales and Medical Representative Organisation (DSMRO), has been taking the lead at coordinating with these groups. He began the conversation with an enthusiastic, “Main toh kisaan ka beta hoon, Madam!” (I am a farmer’s son, Madam!) His team learns of the requirements from doctors and tries to arrange supplies from the bulk-medicine markets in Delhi or other states. “Recently, a network of pharmacists from Telangana couriered a batch of medicines. We are also associated with the Red Cross societies, and when there is a need for specialised medicines, we ask them for help,” Mr. Kumar said.

For doctors regularly visiting the protest sites, schedules have only become more hectic. As they juggle duty hours and health camps, ‘personal time’ has been sparse.

Dr. Taara recalls receiving a panic phone call in early December. The caller was worried about a protestor in Tikri border who was complaining of chest pain since early that morning. “The caller said I was the only person they knew from Delhi. I called them to my hospital and ensured basic treatment was given at the cardiology department. Further medical investigations, not available at my hospital, were needed. It was around 1 a.m. by then. I took them to RML (Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital) for these tests in my car and returned home around 3 a.m. I had been working since morning at the hospital that day already. You can imagine how taxing it is for us these days” he narrated.

Varied solidarities

This is not the first time healthcare workers have stood beside farmers in their struggles. In the summer of 2018, when farmers marched to the Parliament protesting against the deepening agrarian crisis, doctors and nurses joined forces immediately. They treated the protestors for blisters on their foot, low blood pressure, dehydration, sun-stroke, and more. The country witnessed similar scenes during the 180-km farmers’ protest march from Nashik to Mumbai in 2019.

Meera Sanghamitra, an activist with the National Alliance of People’s Movements, delighting in the promise these shared solidarities hold, said, “The farmers’ protest has woven varied kinds of solidarities within itself. The movement is a culmination of public angst against pro-corporate liberalisation and state repression. Shared struggles, years of organising and alliance-building have led to it. The one silver lining that has emerged due to the current regime is heightened public consciousness about the value of diverse solidarities. The fact that these farm laws might affect everyone also makes this increased consciousness inevitable.” She said that while practical bottlenecks remain in mobilising, including the struggle to foreground womxn as equal leaders, there is an immense revolutionary potential in this moment and movement. “We, therefore, need to visualise our movements with this inclusive yet expansive understanding of shared participation by citizens from different vantage points and socially marginalised locations,” she added.

To illustrate what the farm laws – particularly the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020 or the APMC Bypass Act – holds for our future, food rights activist Jean Drèze said in a message for the Kisan Sabha at Guru Tegh Bahadur Memorial: “It is possible that the Central government may replace the physical procurement of agricultural commodities with a national system of deficit payments – where the farmers will be paid the difference between the MSP and the market prices. This may never happen, but if it does, it will be quite a mess and it will go hand in hand with an attempt to rollback the Public Distribution System.” Together, these would exacerbate the food security crisis in the country, and the National Food Security Act will become a paper tiger. Drèze further warns us that the APMC Bypass Act “is poor economics, it fails to address the key issues, and reduces farmers’ control on the marketing system. It will help the central government evade mandi taxes in its procurement of rations, help companies like Adani take over some of the FCI’s (Food Corporation of India) work, and help Reliance conquer the market for farmer’s produce. But, it is unlikely to actually help the farmer.”

Confusions are many

An analysis by Amnesty International in September 2020 found that at least 573 healthworkers had died after contracting COVID-19 in the country. In October, the Indian Medical Association declared around 500 doctors had died of COVID-19, adding: “This also exposes the hypocrisy of calling them corona warriors on one hand and denying them and their families the status and benefits of martyrdom.” Amidst this reality, some healthworkers raised concerns about protests as potential ‘superspreader events.’

When I spoke to Dr. Swati Acharya*, an obstetrician-gynaecologist based in Delhi in early December, she was one month into recovery from COVID-19. She was still feeling lethargic and weak. She said people were taking the disease far too lightly. “Visuals from the protest sites show that many are neither wearing masks nor following physical distancing. Consequences will be disastrous even if 10 people are COVID-19 positive there,” she said. She asked who would take responsibility “for the surge in the number of COVID-19 cases post these protests.”

Dr. Shivam Pandya, a student of surgical oncology and a resident of Ahmedabad, “as an outside-observer of the protests”, called them “the biggest COVID cluster”. “Delhi is a major medical centre for people from neighbouring states. Protest gatherings block traffic resulting in reduced access to hospitals. Ambulances are not allowed free passage through the protest sites,” he said.

In response to claims of reduced medical access, Dr. Bhatti retorted: “Have they seen these protest sites themselves? Farmers do not wish inconvenience on anyone. They even scheduled the Bharat Bandh for only four hours. Ambulances are allowed to pass very smoothly.”

“When people vocalise their dissent about the status-quo, detractors try to give it a religious spin or associate it with political outfits to derail the agenda,” says Dr. Srinivas, who has often volunteered at the health camps. From a farmer’s family in Kanyakumari, Tamil Nadu, he said, narratives of a Khalistani infiltration and ‘KFC langar’ are tactics of “manufacturing public hate against the protesting farmers.”

Dr. Kamna Kakkar, MD, Anaesthesiology, works in both COVID and non-COVID ICUs in a tertiary-care hospital in Rohtak. “My home has transformed into a quarantine centre. We have had a series of COVID-19 infections, with my mother having tested positive at the moment,” said the coronavirus-survivor. She said it was hypocritical to blame protest gatherings in outdoor spaces while opening up bars, cinemas and gyms. “For example, Analysis has shown COVID-19 transmission during the Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests were not due to outdoor demonstrations but due to mass arrests and usage of tear gas by the police.” The solution lies elsewhere, she said, adding, “If the state truly wants to address the fear of transmission, it must devise ways of raising awareness about COVID-19, and perhaps even entrust the police with the task of distributing masks, sanitisers, and winter essentials for the protestors.”

Terming the situation “a government-facilitated disaster”, Dr. Bhatti asked, “What was the need to bring in these laws during a pandemic without consulting stakeholders?” Farmers have repeatedly said they would stop the agitation as soon as the government undertakes to repeal the laws. “Why would the Centre not repeal the laws, form a Parliamentary Standing Committee to hold proper discussions about the reforms and to put an end to this misery? Nothing justifies this adamant and callous behaviour,” he said.

Dr. Kakkar further explained, “The discourse on public health must take cognisance of the systemic inequalities that plague our society. How convenient is it for people to blame the farmers now and forget what has been leading to their suicides and distress? Why forget that poverty and income inequality is also a problem for public health?”

While confusions are many and protests may need to be reimagined during a pandemic, do the disenfranchised have the privilege to wait for the right time to dissent? “It’s like saying don’t try to save yourself when someone is shooting at you! The farmers have not gathered for merrymaking, but to fight for their rozi roti (daily bread), and we are here to support them” Dr. Bhatti said.

* Names changed.

Leave a Reply