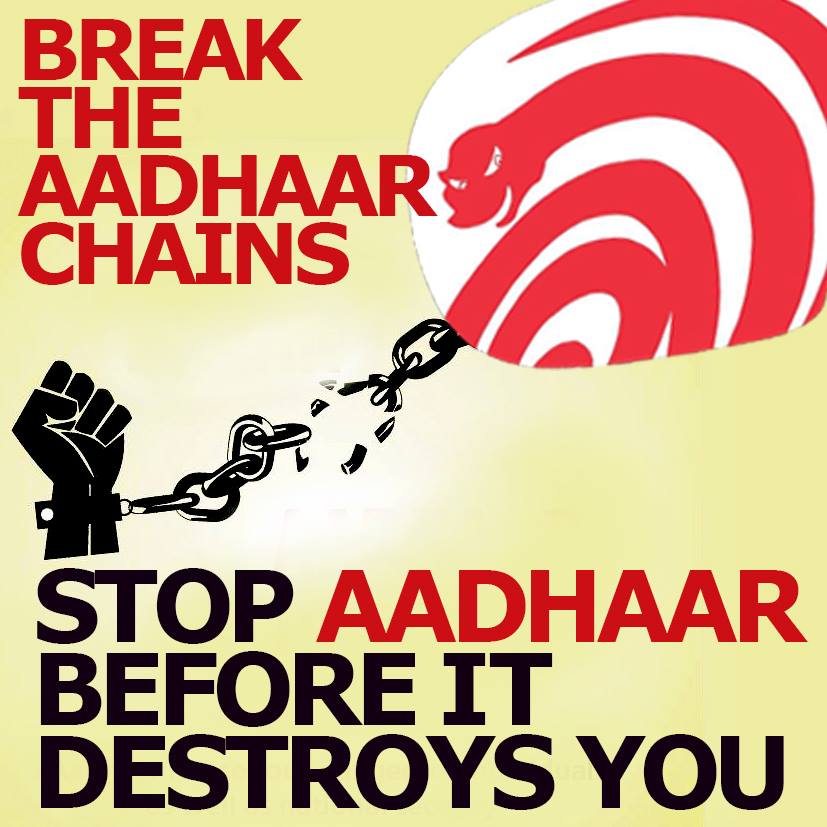

There are no benefits from Aadhaar that cannot be achieved through other technologies. Beneficiaries of welfare should be ‘freed’ from its clutches first as they have suffered its tyranny the worst and longest

It has become impossible to have an intelligent discussion with the government on Aadhaar.

The charge sheet against Aadhaar is endless.

The rule of law appears to not apply: after the Supreme Court issued interim orders in 2015 restraining the use of Aadhaar to a handful of schemes, these orders were violated routinely — and with impunity. Again, if your data is compromised, you have no right to initiate direct legal action; it must be through the UIDAI.

The parliamentary process has been undermined: when worries mounted about the lack of a legal framework regulating the Aadhaar project, the government passed the Aadhaar Act as a Money Bill to bypass the Rajya Sabha, where it lacks majority. The informed legal consensus on this is that the Aadhaar Act does not qualify as a Money Bill.

The technology is unreliable: high rates of biometric failure; bugs reported by hackers; data-security and -protection issues and worse have been in the news regularly since 2017. When these reports come in, the government’s response has bordered on the ridiculous: e.g., citing the thickness of the brick walls of the data centre that apparently ‘protect’ digital information.

The government’s response has also been inconsistent, even contradictory. When the Aadhaar Act was violated by public and private implementation agencies (e.g., by publicly displaying Aadhaar numbers), media whistleblowers and reporters responsible were rewarded with legal action. Meanwhile, the government also claimed there was nothing wrong with displaying Aadhaar numbers!

The government (almost) deliberately misinterprets the charge or ducks the real issue. For instance, the UIDAI CEO argued that the Aadhaar numbers did not ‘leak’ from UIDAI servers but from the Indane website or the Jharkhand government website. For the person whose data has been compromised, it hardly matters whether the thief came in through the door or a window.

Banal, even dangerous, analogies are drawn to justify Aadhaar: e.g., proliferation in the use of the Social Security Number (SSN) in the US. This line of argument conveniently ignores the data breaches (most recently, the massive Equifax SSN data breach in 2017) and its consequences for ordinary citizens or how hard it has been to hold companies like Equifax accountable. Instead of learning from others’ mistakes, we are goaded on to repeat them.

Denial is the other response of the government. For months, the government has denied that there is any problem with the use of Aadhaar in delivering welfare benefits (such as PDS rations and pensions). Even today, it is only because the Supreme Court judges have understood the scale of the exclusion problem that the government has begun to grudgingly accept it in court (only).

An important message that has yet to sink in is that Aadhaar in welfare is pain without gain. At least two studies on the use of Aadhaar for PDS supplies in Jharkhand suggest this. Technology failures (lack of Internet connectivity or failed biometrics) result in inconvenience (repeated trips) and exclusion (denial of food rations). If things work smoothly, people are left exactly where they were before the introduction of this technology. Both studies find little evidence of ‘duplicates’ or ‘ghosts’, a problem Aadhaar could potentially solve.

The government submits that welfare cannot be administered efficiently without Aadhaar. It claims Aadhaar plays a constructive role in guaranteeing the Right to Life. It relies on discredited World Bank estimates to project savings through Aadhaar. The reality is that when names are struck off pension or ration lists because they could not or did not link Aadhaar, the reduction in expenditure from ‘exclusion’ is passed off as ‘savings’.

Those who recommend the use of alternative technologies (e.g., smart cards) are projected as stooges of companies. Meanwhile, former UIDAI functionaries are building businesses using the Aadhaar platform and have pleaded with the Supreme Court to save Aadhaar.

The writing is on the wall: there is no point throwing good money after bad. There are no benefits from Aadhaar that cannot be achieved through other technologies. Beneficiaries of welfare should be freed from its clutches first as they have suffered its tyranny the worst and longest. If Aadhaar stays at all, it should be voluntary with a simple opt-out, which should be guaranteed when exercised.

Reetika Khera is associate professor (economics) at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi

April 27, 2018 at 4:03 pm

The rulers along with the proponents of aadhar are trying to make it mandatory by any means. But they are unable to show any additional use with the aadhar number