NEW DELHI– A plan to provide each of India’s 1.2 billion citizens with a unique identification number has been praised as an essential programme to impose some efficiency on India’s infamously inept bureaucracy.

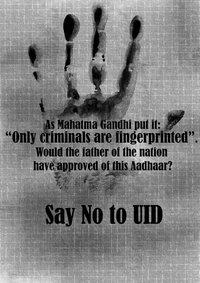

But its opponents have said it is ripe for abuse. The government could use it to spy on its citizens and criminals could steal the data and create false identities.

Since the plan was launched in mid-2010, about 110 million Indians have queued up at data-processing centres across the country to have their irises scanned and their fingerprints recorded.

The unique identification (UID) number that arrives in the post a couple of months later can then be used to apply for welfare benefits and set up a bank account, without the endless form-filling and bribe-giving, which often goes along with proving your existence in India.

Headed by the respected former chairman of IT giant Infosys, Nandan Nilekani, the scheme has been a model of unusual government efficiency.

But the programme is now under threat from the Home Ministry, which has its own biometric database.

It collects not only fingerprints and irises, but also sensitive information such as caste and religion, which it wants to use for security purposes.

A turf war between the Home Ministry and the UID Authority led to a compromise last week. The agencies agreed to share their data to avoid duplication. That allowed Mr Nilekani to collect another 400 million people on to his database. The government is providing more than US$1.5 billion (Dh5.5bn) to merge the databases.

The deal is a boon for the Home Ministry, since it has only registered about 8 million citizens on its National Population Register (NPR).

It is unclear how all this information will be stored and shared, but it has done nothing to allay the fears of activists who foresaw the UID scheme turning into an Orwellian nightmare that could target, rather than help, India’s poorest citizens.

“These schemes are changing the relationship between the citizen and the state,” said Usha Ramanathan, an independent legal researcher and an opponent of UID.

“In the current climate, many of the poor don’t want to be identified because they will be subject to harassment.”

The paranoia is not entirely misplaced. The NPR emerged out of a scheme in the early 1990s to identify illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. More than 40,000 Bengali-speakers were later deported within a three-year period.

Many fear that the new data will be similarly used by parties – such as the ultra-right-wing Shiv Sena in Mumbai – that want to identify and remove migrant labourers from other states.

UID supporters said these concerns could be addressed through legal protections, and should not overshadow its work in streamlining welfare delivery.

One of the UID programme’s main tasks will be to cut out the millions of “ghost workers” that exist only on paper and allow contractors to siphon off extra money from the government.

Payments for programmes such as the employment guarantee scheme – which provides 100 days of work to every adult in rural areas – are already starting to bypass middle men and go straight into verified bank accounts.

It is also expected to provide a “portable identity” for internal migrants, who often find it impossible to open bank accounts or receive welfare benefits outside of their home state.

“In a country where so many people are moving for short-term work or long-term relocation, we have not had a method by which people can take their identity with them,” said Pronab Sen, principal adviser at the government’s planning commission.

“Providing these people with public services has always been a problem. That’s where the UID will be essential.”

But much of its success depends on untested methods and technology. There are immediate practical concerns, with technicians reporting widespread difficulties in reading the worn-down fingerprints of manual labourers and the cataract-blocked irises of elderly citizens. Experts also said that without a proper design, the scheme could prove far less secure than its proponents imagine.

“All it would take to steal someone’s biometric identity is a photograph taken with a high-resolution camera or a fingerprint off a glass,” said Sunil Abraham, of the Centre for internet and Security in Bangalore.

“And once your biometric identity has been compromised, there is no way of re-securing it without surgery.”

He points to the recent incident in which several thousand Israeli biometric identities were leaked on to the internet by Saudi hackers. Stolen identities could be used to frame individuals for crimes or set up bank accounts for money laundering.

“I can see a situation in which a black market for biometric identities emerges,” said Mr Abraham.

Many in parliament share these concerns. Last month, the standing committee on finance rejected a proposed bill that required certain legal protections for people in the UID database.

The committee concluded that the standards were drafted with “no clarity of purpose and leaving many things to be sorted out during the course of its implementation … [it has been] implemented in a directionless way with a lot of confusion”.

Mr Nilekani said he will assess the committee’s concerns. “We will review the security concerns in the next six to eight weeks,” he said last week.

But with trust in the government at an all-time low in India, he will have a lot of convincing to do before his opponents back down.

“Every attempt at regulation in this country has failed,” said Ms Ramanathan. “They say this data will not be abused, but how can we believe them?”

Related articles

- Opposition to the world’s biggest biometric identity scheme is growing (kractivist.wordpress.com)

- Setback to UID – Usha Ramanathan (kractivist.wordpress.com)

- Enrolment saga – Usha Ramanathan (kractivist.wordpress.com)

- We Don’t Trust UID with Our Data: India Inc (kractivist.wordpress.com)

- How reliable is UID? – R. Ramachandran (kractivist.wordpress.com)

Leave a Reply