Photographs by Meenal Agarwal; Text by Madhulika Varma

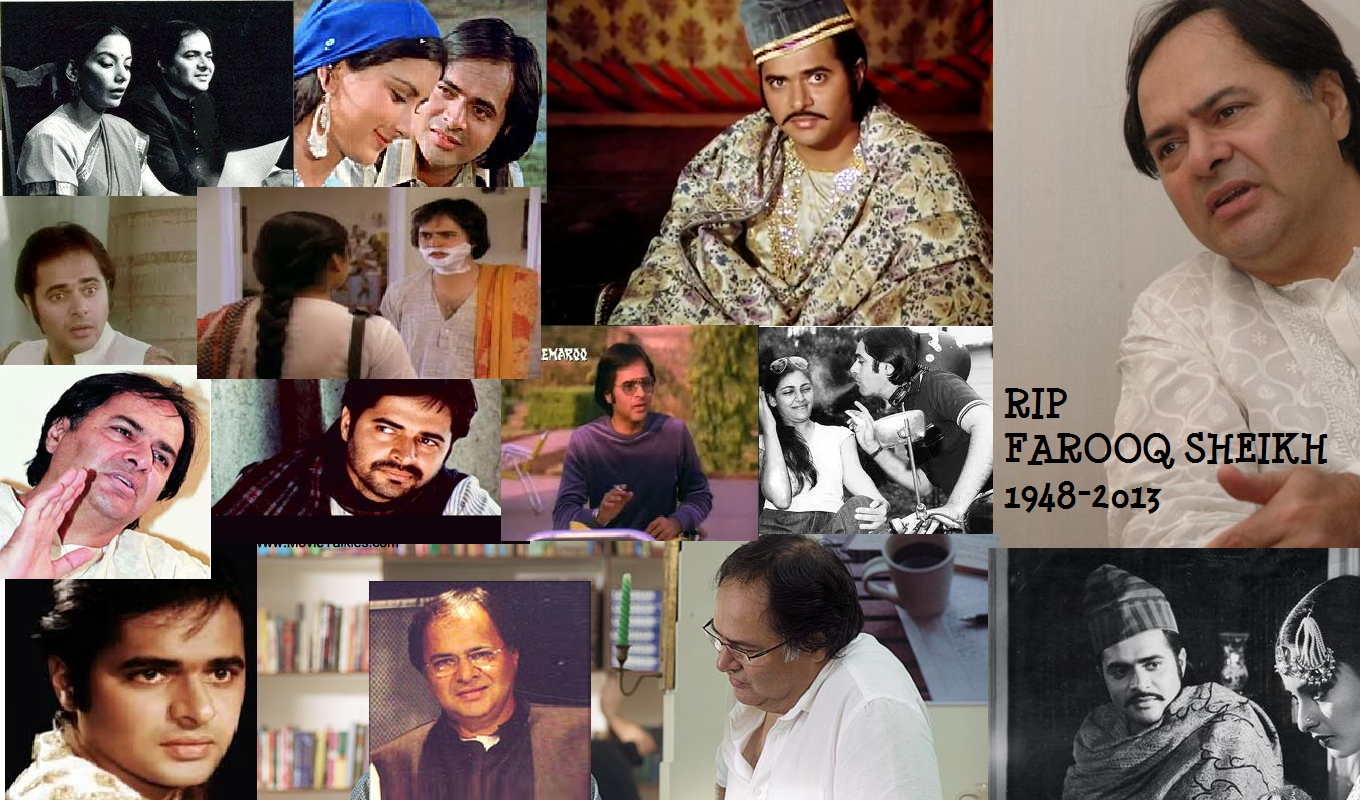

Reticent actor and popular television host,Farooque Shaikh, seems a man too good to be true. Except that Madhulika Varma, discovering a strong, silent type, taps into old friendships, an adoring spouse and sundry acquaintances to draw the whole picture of the nice guy who went missing.

Reticent actor and popular television host,Farooque Shaikh, seems a man too good to be true. Except that Madhulika Varma, discovering a strong, silent type, taps into old friendships, an adoring spouse and sundry acquaintances to draw the whole picture of the nice guy who went missing.

I am on the road to Film City, Mumbai. Large chunks of this once pristine, emerald haven have been gobbled up by an advancing army of skyscrapers. The seductive, wayward, ribbon of a road that once sashayed ahead has now been pummelled into a listless concrete Duh! The earth scents have been replaced by gasoline. You ache for a time lost – before the Shock and Awe Brigade struck and transformed the world into one giant gyrating remix.

Much was swept away by this giant swell that hit town. Including the celluloid male. Too often, he was an excitable, brass-knuckled avenger and you dunked him in the bin along with your frayed film ticket. But occasionally, in an NFDC film, or those crafted by the Benegal/Bangla brigade, you met the everyday man – sensitive, flawed and palpably real, he stayed with you, even walked you home.

You don’t see him anymore. You want to find out why he left. Which is why, I’m on the road to Film City, in search of a man called Farooque Shaikh. The nice guy who went missing. Garam Hawa, Gaman, Bazaar, Noorie, Chashme Buddoor, Katha, Saath Saath, Kissi Se Na Kehna were the films where the actor didn’t hit the high notes, just fleshed out the contours of an everyday-kinda guy. Where Shaikh differed from the Oms and the Naseers was that they had the unwashed, lean and hungry look, while Shaikh, at all times, looked like he had access to a good launderette and that, no matter how grave the crisis, he wasn’t going to skip lunch. And, he oozed chicory charm. Which is why, it is fabled that several of his co-stars and all the pardanashins of Lucknow were seriously smitten by him!

Shaikh resurfaced recently, charm intact…on primetime TV. Jeena Isi Ka Naam Hai, celebrates the lives of many a star with such effortless ease that you began to think it was on auto-pilot. That is, until he left the show. And the centre seemed to fall. It foundered embarrassingly, till the old familiar face returned and restored Jeena to its fluid, familiar format – one of easy banter, with a dazzling moment unveiled, a quiet tear shed.

I am now at studio 10, Film City, where they’re shooting for Jeena and it’s like one has walked into a music video. The place is drowning in cross-currents of perfumes and Britney Spears lookalikes, chewing gum, tottering on stilettos, clad in short skirts – with all the requisite body parts pierced. The guys are all in black, de rigueur in town after sunset. Reigning queen of the song-n-dance scenario, choreographer, Farah Khan’s dancers have come in to root for her, since she is the guest for the day. Shaikh appears, cue cards in hand. A quick comb through his hair, a dab of powder and he’s ready to roll.

Canned in real-time, without a single hiccup, it’s a wrap at 1 a.m. On the slow drive back to Versova, I discover that Shaikh sees himself as the Original Invisible Man. He observes life with such intensity, that often, the observer becomes the observed. So, while he waxes eloquent on Rekha and Ray and Muzaffar Ali, his films and his co-stars, he leaves out a guy called Farooque.

Friends weave in the details about the man, Shaikh. “He’s a perfect gentleman,” says theatre director, Ramesh Talwar, a friend since college days. “I was one of those rough-around-the-edges, Khalsa College types but, I’d acquired a bit of a reputation as a play director. So, Farooque asked me to direct a play for them at St Xavier’s College. He, Shabana (Azmi), they were a large group. When it came to paying me my travelling allowance, they discovered snooty old Xavier’s did not pay even bus fare for Hindi play directors. Well! I did get my money – entirely in two rupee notes. They’d taken a two-rupee collection from every member of the dramatics society!”

And what about the famous Farooque charm? “Oh, the girls didn’t even try to hide the fact that they were crazy about him and he was quite embarrassed by all that attention,” laughs Talwar. “Once, he was doing a play in which he had to wear a dhoti. When I entered the green room, I was aghast to see five beautiful young girls helping him tie that one dhoti. We never got that lucky!”

One of these Xavierites, was a junior called Rupa Vakil who was in the sangeet mandal with the suave Shaikh. Love happened over a song. “It was the only one I ever sang,” says Rupa, who won one of the most sought-after hearts of the ’70s. Thirty-three years later, love fatigue still hasn’t set in. Asked to describe her husband, she rattles off, “He’s a born charmer, he was always good-looking, knowledgeable, very gracious. A male chauvinist in a nice old-world way, he’s the sort who’ll stand up for a lady, open doors and, in all the years we’ve been together, I’ve never ever heard him abuse anyone. But, that doesn’t mean I’ve married an angel. (She had us wondering for a moment there.) He has his flaws and a pretty short fuse….’’

Rewind to the ’70s, when after college, Shaikh was studying law. Theatre remaining his passion, Talwar introduced him to IPTA (Indian People’s Theatre Association). “He used to act in all my little one-act plays,” recalls writer-director, Sagar Sarhadi. “He was family. Bada hi sahaj kism ka insaan hai aur khoobsurat bhi. We never made money doing these plays. In fact, we’re communists you know, so I was always short of money and I wasn’t ever embarrassed borrowing money from these guys…. I still do.” It was here at IPTA that Shaikh was offered Garam Hawa by M. S. Sathyu. “He said there’s no money in it but it’s a film that needs to be made,” recalls Shaikh. “At the time we didn’t think we were making such a significant film. In fact, I was appalled by the way these bureaucrats sitting in the FFC offices were treating accomplished filmmakers. For instance, we were in Agra and Sathyu had to shoot a couple of reels and take them down to the sarkari babus at the FFC and only if they approved, did we get the next instalment to shoot with!” Despite the odds, the searing little saga about the aches of the diaspora, became the benchmark for films on the Partition.

But it was Noorie, produced by Yash Chopra, that gave him his first taste of big success. A love story penned by friend and mentor, Sagar Sarhadi, they were given a free hand. “Yashji told us to go away to some place nice and return with a complete film,” Shaikh recalls. Talwar adds: “Farooque was a known face, virtually a star but we took him second class to this beautiful place in Doda called Kalbhadarwa. It was dangerous even then because all these Pakistanis would infiltrate. And, it was remote. With no hotel and no transport, we lived in a school dorm and got to eat only vegetarian food… poor Farooque. He was such a trouper!’’

Shaikh doesn’t remember the hardships. “Ramesh, Bharat Kapoor – in fact the entire unit except Poonam Dhillon (who was a brand-new beauty queen), consisted of old IPTA friends. Kalbhadarwa was excruciatingly beautiful. Ironically, it had nothing to give to its people… the levels of poverty and unemployment were mind numbing. We’d hired locals to work for us and as we got to know them we discovered there were MAs and BScs who were picking up our plates and doing the dishes. After that it became impossible to put down an empty plate!” And, Noorie, the little film, surprised the world by becoming the biggest hit of 1978!

What was the new celebrity like? Nothing dramatic. “I still travelled by buses and autos. Soon after Noorie, we had a massive transport strike, so Bharat Kapoor, Ramesh Talwar and I used to hitch rides on trucks and milk tankers and the drivers were pretty kicked to see us. In fact, Bharat was a bigger draw because he’d done a film called Gupt Gyan, (a sex film) in which he’d played a doctor and these truck drivers and doodhwala bhayyas would discreetly take him aside and discuss their, er, problems with him.” Says Talwar, about Shaikh, “Even today, if his family needs the car, he’ll give it to them and just hail a taxi and be on his way.”

After Noorie, it wasn’t just the truck drivers who were falling all over him – so were the producers. “But, all they had were rehashes of Noorie. I got offered films like Roohi and Kashmir ki Rooh. I refused every one of them… for two years I did no films, only theatre.” He didn’t need to scrounge because he was a success in the export garment business, at that time.

Then came Gaman. Says Shaikh, “I didn’t know who Muzaffar Ali was. He told me he was working with Air-India and he wanted to make a film about a UP taxi driver, who comes to Mumbai in search of a job and how the city claims him, never lets him go. I liked the sensibility, so I agreed to do the film.”

But the vagaries of parallel cinema. “There was no finance for our kind of films so it was all very informal. Subhashini, who was Muzaffar’s wife at the time, would get home-cooked meals for the entire unit. Sometimes we pitched in with potluck. I was playing a cabbie but I was such a bad driver that once I put my foot on the accelerator, I forgot to take it off. After a couple of crashes, poor Muzaffar would crawl into the taxi, lie down under my feet and operate the clutch and the brakes from there!” The film won a lot of critical acclaim but Shaikh brushes it aside. He attributes the film’s success to Ali’s perfect frames and Shahariyar’s exceptional songs. “We just went along for the ride,” he says, dispassionately.

That’s the way he is. Brutally honest. Talk about his (Satyajit) Ray Experience (Shatranj Ke Khiladi) and he is not exactly over the moon. Coming as he did from the excitable world of hard loving, hard-livin’ IPTA-ites he found The Ray Experience, clinical. “Ray worked like the CEO of a corporate house. He had the systems worked out. Every morning, you were to report to your dressing rooms – be seated with full make-up. Then Ray would come by to greet you – which was a good thing – only, this was his way of keeping track of who came at what time. And, the tenor of his ‘hello’ let you know if he was upset. Discipline was so severe that even poor Sanjeev Kumar never came late, even once! Then, Ray’s vision was just that. His. Leaving no room for the actor to improvise. There was such minute detailing with sketches and all – that it was like a mathematical equation.”

Shaikh’s career’s most unusual team-up came when he signed Umrao Jaan opposite the mercurial Rekha. It was like the coming together of people from two different planets – she from Mars, he from Venus. Shaikh recounts: “Yeah, I had heard all these stories about how difficult she was, how she walked off the sets but I met a different person.” He elaborates, “For our Lucknow schedule, it was the month of January, when the entire North freezes over and we were booked on a night train from New Delhi. We had been told the unit would arrange for bedrolls for us but somebody forgot to do it. So there we were, shivering in our inadequate little woollies. As the night progressed, the berth began to feel like a block of ice. I scuttled over to the top berth and huddled there, teeth chattering. Dinaji (Pathak) had two shawls, so she curled up under them. But the imperious Rekha sat out the night – head covered with her shawl, ramrod straight, like a sphinx. ‘Someone’s gonna get killed tomorrow,’ I remember thinking. I was amazed when we landed in Lucknow and she didn’t say a word!”

Shaikh continues: “She would torment us by getting dressed to her teeth in all that Umrao Jaan finery and report for work at 7 a.m. every frozen morning. You can imagine the flurry when Rekha madam is in the foyer ready and waiting and we’re still in our pyjamas!”

There’s more than chauvinism here. Shaikh has a real respect for women. “They have an honest, far more intense way of looking at things,” he says. That’s why he cherishes his association with director, Sai Paranjpye. “I think both Chashme Buddoor and Katha worked specially because they were so well written by Sai. She had a great eye for detail, for picking up the commonness of life and celebrating that.”

But those were happier times. Today they’re romancing the belly button to the strains of Ishq kameena. And, many die-hard romantics are finding it hard to stay on the road. But people like Shaikh have always taken the road less travelled. If cinema turns sassy, he’ll go do a Srikant on Doordarshan. If Ekta Kapoor corners TV with her Kanjeevaram Khandaan kitsch, he’ll go do a play that has no props, just two people declaring their love through letters on a stark stage (Tumhari Amrita). If the stage goes bawdy, he’ll go work in his stables (he has 20 horses) in his village in Gujarat.

“Bilkul sufiana andaz hai,” says Sarhadi. (He has an absolutely saint-like attitude) “Na peeta hai na pilata hai. (He does not drink nor does he offer to others) Par uski ek bahut badi kamzori hai – achcha khana. (His one big weakness is good food.) Achcha Mughlai khana ho to badi sanjeedgi se khata hai. (Good Mughlai food is eaten very seriously)” Talwar reveals an even bigger weakness. Friends. “He’s a true friend. If he even suspects that a friend is in need, he’ll come by and drop some money, say, ‘Mere paas aise hi pade thhe.’ (I had some money lying around) When my daughter was in hospital, he landed up at twelve at night and sat through the ordeal with me,” he says, visibly moved.

“He’s a very caring friend,” agrees wife Rupa. “If a friend has gone away and his family is alone in town, he’ll remember to call up and check on them, no matter how busy he is.” As for his own family – he’s daddy to Shaista and Sama, both his little darlings, (they’re actually 22 and 19).

“He’s cooled down a bit as a parent now, otherwise he was daddy at full throttle,” says Rupa. “He is a very demonstrative sort of father. If they’re away, he’ll SMS them five times a day, asking ‘How’re you bachcha? Have you had your lunch?’ With his daughters, there are so many kisses flying around that my dad used to call him Moochoo Master. He’ll just drown you in love,” says Rupa, laughing.

She should know. She’s seen its most profound expression. Fourteen years ago, she contracted trijeminal neuralgia. Because of this ailment, she suffered from excruciating spasms of pain. For 14 years, she would wake up in agony ten times in the night and ten times he would sit up with her, helping her through her pain. “I wasn’t there a hundred per cent as a mum or wife but, he’s been by my side, for not one or two, but 14 years. I have never seen even a hint of impatience in his eyes – his only desperation has been to free me from this pain. He has taken me to Mecca, tried Tibetan medicine, acupressure, everything.”

What would a perfect world be like, for him? “In Equilibrium. That’s all,” says Rupa, simply. So that he can sit back, remote in hand, with the smell of home-cooked meals wafting around him. Or better still, he’d love to drive down to Amroli, his native village in Gujarat and watch the burgundy evenings swirl, over a cup of tea with Sallauddin.

Who’s Sallauddin? To you, he may look like a horse. All Shaikh sees is a very old friend.

Read more here- http://www.verveonline.com/27/people/farooque/full.shtml

Leave a Reply