New Delhi:

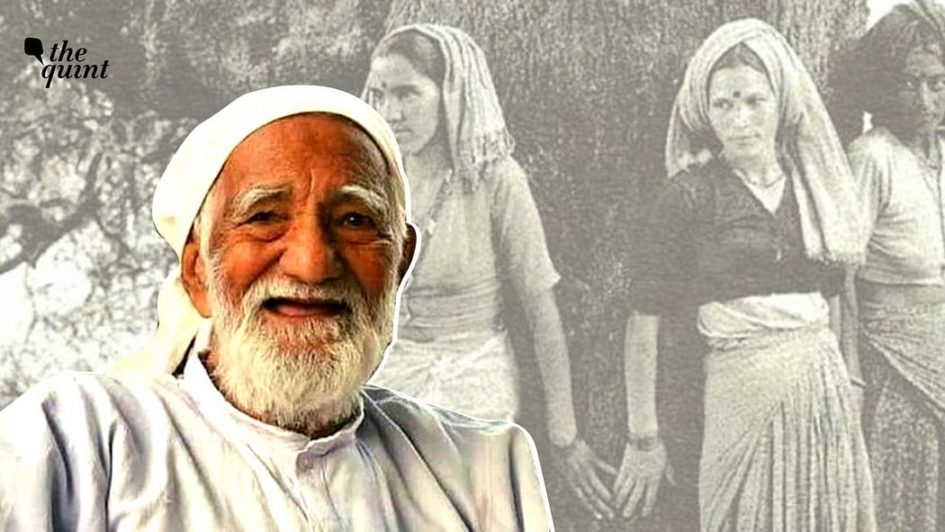

Environmental activist Sundarlal Bahuguna, a pioneer of the Chipko Movement against deforestation in the 1970s, died in Uttarakhand this afternoon. He was 94 years old.

His death was declared by the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) Rishikesh where he was admitted for Covid treatment, ANI reported. Mr Bahuguna died at 12.05 pm AIIMS Rishikesh Director Ravikant said.

One of India’s best-known environmentalists, was admitted to the hospital on May 8 after testing positive for Covid. His condition turned critical last night, with his oxygen level dropping drastically. He was on CPAP therapy in the hospital’s ICU.

Condoling his death, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said the late environmentalist manifested “our centuries old ethos of living in harmony with nature.”

Uttarakhand Chief Minister Tirath Singh Rawat expressed sadness saying it was Mr Bahuguna who turned the Chipko movement into one of the masses.

A long-time follower of Gandhian principles, Mr Bahuguna transformed the spontaneous Chipko Movement into a turning point in India’s forest conservation efforts.

Chipko means “to hug”. During the 1970s, when reckless cutting of trees began affecting people’s livelihoods, villagers in Uttarakhand’s Chamoli began to protest. The tipping point came when the government, in January 1974, announced the auction of 2,500 trees, overlooking the Alakananda river.

When the lumberjacks arrived, a girl who saw them and informed the village heads. Women in large groups came out and stopped the lumbermen by hugging the trees, signifying an embrace, despite being threatened. Three local women, Gaura Devi, Sudesha Devi, and Bachni Devi, championed the cause.PromotedListen to the latest songs, only on JioSaavn.comhttps://www.jiosaavn.com/embed/playlist/85481065

Mr Bahuguna gave a direction to the movement and his appeal to then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi resulted in a 15-year ban on chopping of green trees in 1980.

4CommentsLater on, he used Gandhian methods like satyagraha and hunger strikes to protest the building of the Tehri dam in Uttarakhand on the Bhagirathi river.

What Oxygen Really Meant in Sunderlal Bahuguna’s Futuristic Vision

It is a telling irony and a deep message, that Bahuguna succumbed to a pandemic that made his body crave oxygen.

When the plains of India and its major cities were rocked by the JP movement led by late Jayaprakash Narayan in 1974 with unrest that eventually led to the imposition of the Emergency by beleaguered Prime Minister Indira Gandhi a year later, the hills of what is now called Uttarakhand were alive with another protest — against the cutting of trees that denuded mountains and threatened livelihoods in an environment that was increasingly less idyllic.

The death of tree-hugging Chipko Movement leader Sunderlal Bahuguna aged 94 due to COVID-19 brings back several memories.

But towering above them all is his vision for a development model in which oxygen-emanating trees, that swap carbon for clean breathing, holds centre-stage.

It is a telling irony as well as a deep message, that Bahuguna has passed away from a pandemic that made his body crave oxygen. It is a stark reminder that his life, that of his assassinated idol Mahatma Gandhi, was a message.

My Meeting with Sunderlal Bahuguna

I remember trudging with a backpack from a mountain bus stand at Tehri on a cold January day 1990 to meet Sunderlal Bahuguna on the banks of the Bhagirathi, which meets the gurgling Alaknanda at Deoprayag downstream to be called the Ganga, or the mighty Ganges.

I recall his warm smile, his glowing eyes shining below his green headscarf and above his scraggly beard, and his most pleasant manners as I learned about his cause and his concerns.

If I recall right, he wrote out his answers to my questions as he was on a ‘maun-vrat’ (vow of silence) as well. I hope I will one day find some cherished hand-written notes in a dusty corner of myalmirah.

Bahuguna’s 11-day fast saw two influential visitors — then Environment Minister Maneka Gandhi and then Energy Minister Arif Mohammed Khan (now Kerala governor). He ended the fast only when the energy ministry agreed to stop work on the Tehri dam and review it. Alas, it was a failure in the long term.

Bahuguna’s Significance

Large parts of the valley had already been dug up and earth-movers were busy. But the social power of the man who went on to win the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian honour, in 2009, was evident despite his simplicity and stubbornness. The power, however, waned over the years as concerns for the environment became overpowered by ambitions of muscular industrial growth under an economic reform programme and political changes.

However, Bahuguna’s special significance lies in two things:

- first, he was India’s own homegrown environmentalist standing in stark contrast to post-industrial activists of America and Europe

- secondly, he triggered increased concern for the environment across urban India in an indirect way that must have inspired many a youngster today — many of whom may have barely heard of him or his work

Bahuguna Wanted a Low Carbon Footprint Long Before the Term Became Fashionable

I would call Sunderlal Bahuguna a ‘Native Green’ or an ‘Alt Green’ — a far cry from developed-world environmentalists whose movement is substantially focused on climate change, nuclear energy and industrial pollution. If the environmentalists of the West were leading lifestyles that already reflected a century or more of industrialisation, and often talking of new technologies to reverse or check the problems created by industrial technologies, Bahuguna wanted to stop polluting industrialisation from happening in India even before it acquired significant scale.

He wanted a low carbon footprint decades before the term became fashionable in Europe or America. He was happily rural, happily pre-industrial and happily a mountain man. If I recall right, ,he preferred the higher reaches of the Himalayas compared to the less oxygen-rich lower hills.

Sunderlal Bahuguna’s Legacy and the Way Forward

There is still room for Bahuguna’s native wisdom mixed with Gandhi’s idea of a village-oriented ‘Swaraj’ (self-rule). It is true that the lure of the productivity gains of industrialisation, and the utility of gadgets that connect the world and beyond, is strong. But it is equally true that there might be fewer congested slums choked for oxygen in urban cities amid a pandemic, if his ideas had been followed keenly.

His life and his mission were rich with the oxygen of native wisdom and a frugal or simple lifestyle. Some of the new technologies actually make his ideas more doable — if we could mix them in the right configuration of policies.

As large sections of the world gasp for breath in the grips of a pandemic that attacks the respiratory system, it might make sense to consider that Sunderlal Bahuguna’s life and work are like a breath of fresh air waiting to be inhaled.

Leave a Reply