The fact that Dubey was yet to be charged under any law while Rao has been charged under a special law should not blind us to the essential similarity they share — the state took unfair advantage of its custodial power over them. But the real danger such cases pose is that they always carry in their background the suggestion of popular support, which sometimes ripens into an explicit claim.

Written by Satish Deshpande | Updated: July 24, 2020 9:59:10 am XRao is 81, has tested positive for COVID-19, and has been in jail for the past 22 months.

XRao is 81, has tested positive for COVID-19, and has been in jail for the past 22 months.

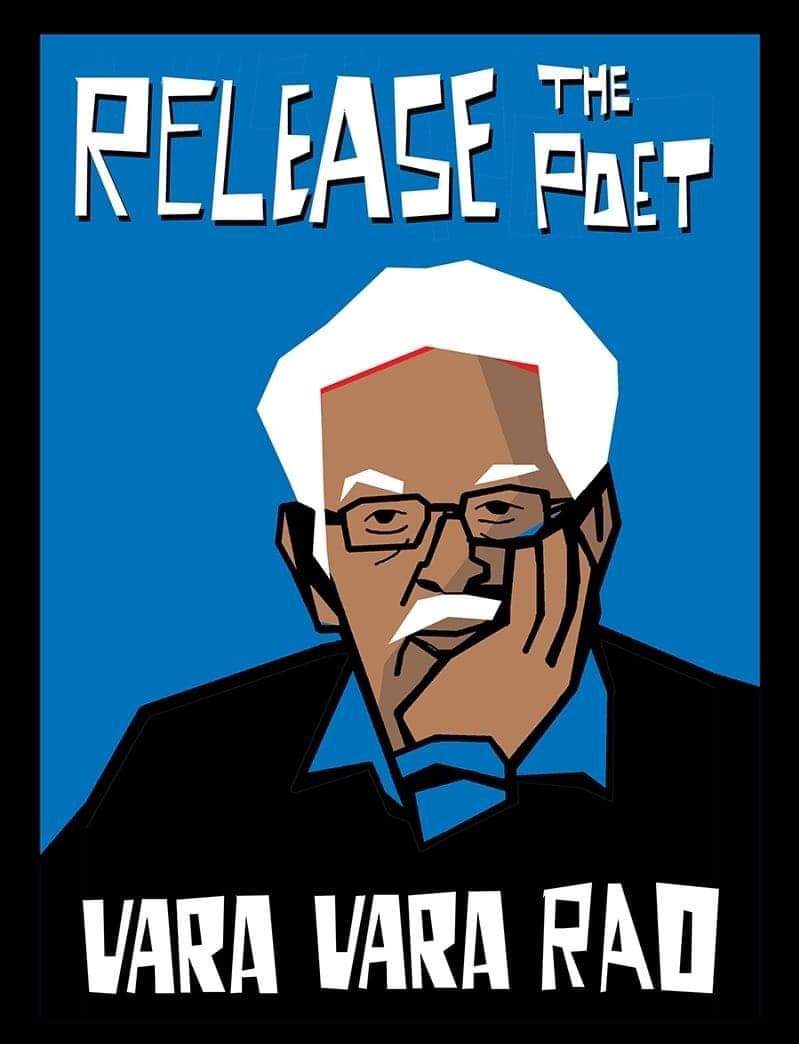

The National Investigation Agency (NIA), which has custody of the Telugu poet and iconic leader of the ViRaSam (Revolutionary Writers’ Association), Varavara Rao, arrested in the Bhima-Koregaon case, has opposed his bail plea arguing that he is “trying to take undue benefit” of the COVID-19 pandemic and his advanced age. Rao is 81, has tested positive for COVID-19, and has been in jail for the past 22 months. Given that these facts are not contested by the NIA, the rational reader is compelled to reflect on the meaning of the phrase “undue benefit”. Who is trying to take undue advantage of what here?

This question is best answered via a second comparative one: What does the recent encounter killing of the Uttar Pradesh don Vikas Dubey have in common with Rao’s current situation? This may seem a strange question because of the obvious differences.

The don is dead, the poet is not. Moreover, since the UP authorities have stopped short of claiming that the guns which killed Dubey fired themselves and that the policemen holding them were helpless spectators, the don’s death was caused deliberately. By contrast, the NIA can claim to be a blameless bystander because it did not cause the poet’s infection.

There are bigger differences of social identity that weigh more heavily on public perception. One aspect of their identity is what Dubey and Rao “do”, and descriptions like don and poet may be considered biased. Dubey could be described as a social worker dedicated to solving the problems of overworked politicians. Rao could be described as a dreaded urban-naxal. Another aspect of identity is who they “are” in the eyes of society. Coincidentally, both Dubey and Rao were born as Hindus, Brahmins and males, but their attitudes towards these attributes probably differ. For example, the former was a devout temple-goer while the latter is a declared atheist.

Such differences could be multiplied, but they are dwarfed by one fundamental similarity. Both Dubey and Rao voluntarily surrendered themselves to police custody when the police — and by extension, the state — took “undue benefit” of its power to harm them. That this harm has resulted in death in one case but “only” a potentially lethal infection in the other is immaterial. If Rao were to miraculously survive COVID-19 despite his advanced age and pre-existing conditions, the credit for this would not go to the state. On the other hand, if he were to succumb, the state would be squarely to blame.

Editorial | First, Varavara Rao must get the urgent medical care he needs — that is his right

This is not unfair because of the nature of state custody. When a law-abiding state imprisons citizens accused of crimes, it automatically assumes custodial responsibility for their well-being. Custodial responsibility is the other side of the coin of the legal deprivation of liberty — or imprisonment — and it is morally if not legally enhanced in the case of prisoners awaiting trial. That is also why, generally speaking, bail is the rule and jail the exception. But Rao, his 10 co-accused in the Bhima-Koregaon case, and an unknown number of others across the country, have been charged under a special law with stringent bail provisions, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. Effectively, the NIA argues that persons accused of crimes against the state should be kept in jail indefinitely based on suspicion alone, even if the accused is 81 years old and COVID-positive.

The fact that Dubey was yet to be charged under any law while Rao has been charged under a special law should not blind us to the essential similarity they share — the state took unfair advantage of its custodial power over them. But the real danger such cases pose is that they always carry in their background the suggestion of popular support, which sometimes ripens into an explicit claim.

Every child is taught that the law treats everyone equally because it is, and it should be, neutral towards all social identities. But every teenager knows that it is not, and many adults begin to believe that it need not be. The legitimation of authoritarianism begins with what people like to call “realism”, which is really a sort of default cynicism. Everyone knows that murder is not always a crime, because if Dubey had led a lynch mob or incited a riot against the right kind of victims, he would be hailed as a hero.

The terminal — but not necessarily short — stage of authoritarianism is reached when it yokes together an aggressive majoritarianism and a fact-resistant sense of victimhood. Across the world today we see the emergence of a new “authoritarian populism”, where regimes backed by socially dominant groups with a victim-complex have captured electoral control of the state. They are led by charismatic dictators who personalise state power and begin erasing the functional differentiation and mutual autonomy of legislature, executive and judiciary. They turn the liberal state apparatus inside out, negating its neutrality and turning it into a weapon to be used against whoever dares to disagree with them.

When played by authoritarian populist regimes, state vigilantism becomes a lethal game without rules. The efficient production and dissemination of mediatised narratives of popular support serve to justify and eventually normalise pervasive illegalities, producing durable forms of impunity that damage institutions permanently. Damaged institutions behave arbitrarily because they obey the whims of their masters rather than the law. That is why, though they do not matter as individuals, and though we may disagree with or even despise their politics, we must protest both the murder of Vikas Dubey and the risking of Varavara Rao’s life. Because every conceivable kind of politics is threatened when due process is re-defined as “undue benefit”.

This article first appeared in the print edition on July 24 under the title “The don and the poet.” The writer teaches at Delhi University. Views are personal IE

Leave a Reply