Report by Bebaak Collective, December 2022

Bebaak Collective (‘Voices of the Fearless’) was founded in 2013 as an informal association of grassroots activists to advocate for the rights of Muslim women and community. It is a platform for engaging with feminist thought and practice, human rights issues, and the anti-discrimination struggle. It has been working in Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan. With the rising onslaught against marginalised communities, the Collective has evolved into an advocacy group that strongly adheres to constitutional values and believes that the rights and principles enshrined in our constitution are inalienable from every Indian citizen, irrespective of their caste, gender, sexuality or religion.

Relatives of a victim of the Delhi pogrom 2020 in mourning. Source: The Guardian

Foreword

Mental health and its socio-political determinants are beginning to emerge from a shroud of silence and stigma into public discourse. There are several possible reasons for this, the most visible being the pandemic and the many narratives of suffering it brought to the fore from among the most vulnerable sections of society. Even before the pandemic, the relationship between social disadvantage and the mental health of certain communities and groups (some more than others) has been studied in the Indian context. Some examples of these include the mental health of women, homeless persons, Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi communities, and queer and trans persons. However, the mental health of Indian Muslims has been severely underrepresented and almost invisible within the mental health or development literature in India.

In a recent, first of its kind, study providing population-level evidence on caste, religion, and mental health in India, Gupta and Coffey report that Scheduled Castes and Muslims have worse self-reported mental health than higher caste Hindus and that Muslims are substantially more likely to report sadness and anxiety as compared to upper-caste Hindus, even after controlling for age, education, assets, expenditure, state of residence, and rural residence.1 Another study seeking to understand the impact of communal violence on mental health has indicated a higher prevalence of mental disorders among Muslims in the post-riot context.2 Similarly, studies from the Kashmir Valley point to high rates of mental disorders, including depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder, among Muslims in the context of chronic political conflict and exposure to multiple traumas.3

All of these, while drawing much-needed attention to the mental health concerns faced by Indian Muslims, do so by using clinical parameters of mental illness and its magnitude. This is not to undermine the value of these research studies, as they make a compelling argument that links mental illnesses and suffering to socio-political and cultural contexts of violence, brutality, discrimination, and marginality. While appreciating the significance of this literature, I wish to draw the attention of the readers to other critical frames that have sought to centre the lived experiences of marginalised communities to create newer, situated knowledge frames that lend voice to their experiences. This report, to my mind, is the beginning of such an effort in the Indian context in redefining the meanings of mental health, selfhood, resilience, and survival among Muslims in India. It has not been authored by mental health professionals or “psy experts,” but by a collective of grassroots activists advocating for the rights of Muslim women and the community. The strength of the report lies in the close relationship between the activists-authors of this report and the lives they seek to represent.

Dr. Samah Jabr, chair of the mental health unit at the Palestinian Ministry of Health, says the following in the context of using available/western categories of mental illness to describe the psychic experiences of Palestinian people:

Clinical definitions of post-traumatic stress disorder do not apply to the experiences of Palestinians. PTSD better describes the experiences of an American soldier who goes to Iraq to bomb and goes back to the safety of the United States. He’s having nightmares and fears related to the battlefield and his fears are imaginary. Whereas for a Palestinian in Gaza whose home was bombarded, the threat of having another bombardment is a very real one. It’s not imaginary. There is no ‘post’ because the trauma is repetitive and ongoing and continuous.4

Dr. Jabr adds, “I think we need to be authentic about our experiences and not to try to impose on ourselves experiences that are not ours.” The present report too steers clear of diagnoses of mental illnesses and seeks to articulate the impact of communalism on the social fabric of Muslim existence in India. In doing so, it uses frames such as “social suffering,” which refers to the range of devastating injuries, pain, and damage that social, political, and institutional power inflict on the human experience.5 Mental health is used in this report to refer to everyday micro-actions such as “the stiffening of backs in public places” or to life-altering decisions such as choice of vocation, access to education, and financial stability. It includes affective experiences of fear, continued isolation and hurt, remembering and forgetting, and searching for hope and a political future.

While describing what constitutes good mental health in the Palestinian context, Dr. Jabr says, “… it is to be able to have critical thinking and to maintain your capacity to empathise.” This report, foregrounding the institutional betrayal and state excesses against ordinary Muslim citizens, activists, and journalists, asks us to think of what good mental health would possibly look like for religious minorities in India today. And what conditions of living are essential to make this possible?

KP/ Ketki Ranade,

Faculty, Center for Health and Mental Health,

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

1. Introduction

1.1 Political Isolation of Indian Muslims: Violence of the Law

The role of the law in systematically isolating and alienating Indian Muslims can be seen in its emboldening of both the Hindu majoritarian imagination and its grassroot efforts. The liberal idea that legislation provides and guarantees rights, dignity, and equality of justice to individuals has been emptied of its emancipatory potential for Indian Muslims under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government.6 The everyday life of “law and order” has assumed the “state of exception,” leading to routine implementation of stringent laws meant for situations that threaten public order or national security.7 It has also included the introduction of laws that sustain and reinforce the idea that Muslims pose a national and existential threat to the majoritarian conception of India as a “Hindu” nation. The cumulative effect of the “state of exception” is the gradual erosion of legal and constitutionally guaranteed freedoms of life, liberty, equality, and religion as well as an increase in violence, at the hands of both legal and extra-legal actors, towards Muslims.

The National Crime Records Bureau data for 2019 shows an increase in the application (as compared to its use in 2016) of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).8 This law, under its broad definition of unlawful or terrorist activity, is infamous for its use in targeting dissidents, allowing prolonged detentions without a trial, and precluding the possibility of bail as the charges of guilt are accepted on a prima facie basis. The arrest of activists involved in the anti-CAA-NPR-NRC movement under the UAPA is one example of the blatant and indiscriminate use of the law, as thirteen out of the eighteen accused are still in jail, without the likelihood of bail or the commencement of a fair trial. Muslim journalists involved in exposing the role of the Modi government in abetting violence against Muslims have also come under the scrutiny of the state.9

The increase in the number of anti-Muslim laws is a testament to how precarious the constitutional rights of Muslims are. For instance, the laws aimed at cow protection and curtailing religious conversion10 are dangerous in not only how they seek to target Muslims (even when the major exporters of beef continue to be Hindus), but because of the process of prosecution put in place by their stipulations. These laws are based on reversal of the usual practice by shifting the burden of proof from the state to the individual. Another bill, premised on the anxieties of demographic takeover by Muslims (or the myth “population jihad”), proposes the prohibition of people with more than two children from accessing government jobs and welfare schemes in Uttar Pradesh.11

The Citizenship Amendment Act, 2019 (henceforth CAA), along with the National Register of Citizens (NRC), were the most explicit ways in which they endangered the citizenship and legal rights of Indian Muslims. The fear of “infiltration” by “illegal migrants” (mostly seen as Bangladeshis) provided the rationale for implementing the CAA-NPR-NRC, which has the scope of large-scale exclusion and disenfranchisement of Indian minorities. According to Niraja Gopal Jayal, “infiltrator” has become a metonym for the Muslim and feeds the xenophobia that provides cover for the yearning to get rid of even Indian Muslims.”12 The example of the Assam NRC, a process supervised by the Supreme Court to make people prove their citizenship, left out 1.9 million people from its final list.13 The history of impunity for crimes against minorities under Bharatiya Janata Party rule,14 seen in light of the use of law-making to implement an all-India NRC, pushed the possibility of detention camps and losing one’s rights as a citizen towards its full realisation.

The majoritarian ideology is slowly materialised through the instrumentalisation of law as well as its “irregular” functioning. Mohsin Alam Bhat has argued that this includes the routine violation of existing laws, as seen in the violation of Municipal Acts by the Delhi Municipal authorities to undertake demolition drives in Jahangirpuri, and its legitimation at the level of legal norms and popular consent through Hindutva mobilisation. The result of these processes is “subordinated citizenship” for minority citizens, as they are “subjected to grave and constant vulnerability of rights violations without any meaningful recourse to institutional checks and the rule of law.”15 Therefore, the functioning of the law is central to the abetting and normalisation of violence inflicted upon Muslims by both the state and extra-legal actors.

1.2 The Unfolding of Genocide: Everyday humiliation and dehumanisation

Gregory Stanton, an expert on genocidal violence, alerted us to the imminence of genocide against Indian Muslims in January 2022.16 The alarm was based on the reality of sustained, everyday instances of communal violence in India. The concept of “jihad” is reflective of the majoritarian community’s sense of being beleaguered by the supposed dominance and strength of Muslims.17 It has been multiplied to create several situations of crisis such as “Corona Jihad”, “Love Jihad”, “Flood Jihad”, “Land Jihad” and “UPSC Jihad.” This paranoia has been used to criminalise mundane and routine activities undertaken by Muslims such as offering namaz in public spaces, selling meat and vegetables, taking government exams, courting people outside their religion, and putting up Whatsapp statuses congratulating the Pakistan cricket team.18

Post-2014, the changes in the political architecture of the country have also included the extension of the right to exercise physical and symbolic violence, supposed to be the monopoly of the state, to militia groups and organisations. Taking the case of violence against Muslims in the form of cow vigilantism in Haryana, Christoffe Jaffrelot has shown the collaboration between the local police, politicians and gau rakshaks in running cow protection militias as well as formal government bodies.19

The increase in the number of vigilante groups, forming the Sangh Parivar, such as Gau Raksha Dal, Yuva Hindu Vahini and Hindu Sena has not been without state support. These organisations have been behind the spike in cases of individuals being targeted on the basis of their religious identity. The cases include not just overt harm to person and property but also forms of humiliation by forcing them to chant Jai Shri Ram (slogan used by right-wing groups to proclaim the Hindu character of the nation), removing garments of religious significance, and impeding their access to places of worship, employment and education. This humiliation forms a part of “institutionalised everyday communalism” 20— a concept that points to how outbursts of violence in certain pockets and regions as “riots” have been replaced by planned and dispersed forms of vigilantism.

The architecture of anti-Muslim violence includes social media with its calls for genocide against Muslims through the taking up of arms,21 circulation of videos, messages, and memes painting a dehumanising image of Muslim men as excessively virile and women as submissive,22 creation of apps auctioning off Muslim women,23 and incessant abuse targeted towards Muslim journalists and activists.24 The offline manifestation of such online hate campaigns was seen at the time of Delhi pogrom in 2020. Whatsapp and Facebook groups were instrumental in organising and mobilsing anti-Muslim sentiment and directing action by identifying and attacking Muslim neighbourhoods, places of business and persons.

The role of mainstream news media in propagating conspiracies about minorities due to the complex workings of corporate sponsorship, television rating points (TRP), and self-censorship in limiting press freedom and ethical journalism also needs to be noted. Taking the example of Aaj Tak and India Today, Tazeen Junaid has shown that their dominant representation of Muslims is through negative stereotyping. Other strategies used by mainstream media to demonise Muslims include doctored images and videos and sensationalist media trials. The idea that Muslims are behind the conspiracies related to the spread of COVID-19, or forced religious conversion, is widely disseminated by news channels and accepted as fact by their audiences. 25

The ubiquity of anti-Muslim messaging on social and mainstream media, its repetition in political speeches, its entrenchment within legislation, and the absence of accountability structures for perpetrators of anti-Muslim violence are indicators of the systematic dehumanisation of Indian Muslims. The totalising effect of these developments is the creation of an environment where Muslims are victimised through economic boycotts, vigilante violence, destruction of property, unfair arrests, and imprisonment. The concerted efforts to create popular consent for the multifaceted nature of Islamophobia and the fact that it continues to spread due to social and state sanction are recognised as a “process” where, through small but consistent means, the modes of survival of Indian Muslims are being broken down as well as the moral and social consciousness of the majority communities, which would allow the formulation of empathy and solidarity with the persecuted group.

1.3 Studying mental health or the changed psycho-social life of Muslims

Contemporary debates regarding the precarious condition of Muslims in India have revealed the impact of religious discrimination on the education and livelihood of the community. For instance, the targeting of women who wear hijab results in the denial of education and employment,26 the boycott of Muslim vendors contributes to systemic marginalisation of the community, the housing discrimination against Muslims leads to spatial segregation, 27 and the unequal treatment meted out to Muslim gig-workers deepens inequality. 28

Within these debates, the subject of mental health has not yet found major grounding. The existing scholarly literature on the relationship between communalism and mental health has focused on the diagnosis of mental illnesses such as PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) through a study of symptoms like sleeplessness, depression, and the inability to focus among riot victims. 29 Others have looked at the responsibility of the health care system in responding to the complexity of social, psychological and physical problems faced by sexual violence survivors of the 2002 Gujarat pogrom.30

Recent studies have also challenged the dominant methodology of identifying PTSD as the only mental health problem associated with going through a natural or social disaster. Instead, representation of communal violence in documentaries such as the Final Solution (2004) have provided key insights into the ways in which survivors craft narratives around their experience of suffering. They have identified the kinds of problems faced by the Gujarat pogrom victims: a feeling of being overwhelmed by losses, relational disruptions, forced identities, and the denial of justice and equity. 31 There have also been attempts by writers and journalists to document stories of distress faced by Muslims, especially the Muslim youth, in light of growing communalism in the country. 32

Taking from these recent attempts to narrativise the experience of distress created by communalism, this report seeks to problematise and broaden the conversations around mental health. The discourse on mental health has largely been dominated by the privileged, with its emphasis on the individual at the expense of excluding the effects of political violence on members of a persecuted community.33 In an interview with Bebaak Collective, Shamima Asghar,34 a mental health practitioner based in Bangalore, argued that mental health in its clinical practice can be extremely individualistic. She pointed out that mental health practice, as a way of dealing with trauma and suffering, does not investigate the root of violence but instead aims to mitigate its ill-effects on those impacted by it. It is a way of saying that the violence you endure will remain, you simply need to learn to live with it.

This report adopts the concept of “social suffering” to bridge the gap between experiences of communalism and mental health practice. Social suffering refers to an “assemblage of human problems that have their origins and consequences in the devastating injuries that social force can inflict on human experience.”35 This experience of individuals refracted through social and political realities is relevant to understand how communalism makes “things not quite right.” The report has, therefore, tried to understand the prolonged effects of communalism in the form of unease, distress and disruption in the lives of victims of overt communal violence. The idea of social suffering helps us to analyse both the extent of injuries as well as the ways in which people fight back and rebuild their lives. It collapses the distinction between the individual and the collective, physical and psychological, illness and treatment in order to reveal that these human relationships and experiences are socially and politically mediated and constructed.

This report is, therefore, written with the aim of showing how mental health can be an important indicator for understanding social hatred and state persecution faced by Indian Muslims. We recognised after our interviews with the victims of hate crimes and riots that mental health or a discussion on people’s habits, feelings and relationships, is a window into the reality of how communalism has changed the everyday life of Muslims. Mental health, therefore, is the metric to understand the otherwise unspoken effects of communalism: the stiffening of backs in public places, continued isolation and hurt, hypervigilance, and search for hope and a political future.. Such an analysis requires us to move beyond finding the remnants of a violent episode through the diagnosis of mental disorders like PTSD or depression. Our report has pushed us to accept and articulate that the study of mental health needs to begin with the understanding of everyday life, in how our life and predominant thoughts around our future, health and financial stability are altered by the experience of violence. Therefore, it is inextricably linked to the larger story of communalism. It validates and confirms broader patterns of persecution and exclusion of Muslims, but also enables a closer look at how individual Muslim lives have been affected.

2. Methodology

We spoke to a wide range of people: Muslims from different classes and castes, with differing levels of education, based in the states of Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Assam, and Gujarat. These interviews were conducted over a period of six months, from February to July 2022. The factors that tie these people together are their Muslim religious identity and their proximity to communal violence. We kept the circle wide and spoke to activists who have been imprisoned, friends of activists, families of men who have been lynched, therapists who treat Muslim patients, families of riot victims, and several family members of imprisoned men, among others.

Our research questions were geared towards understanding people’s feelings about their experiences of communalism. We asked people to recount their stories to us and tell us how they felt. Many times, the people we spoke to were in the midst of responding to an ongoing situation: one person we spoke to was hiding from the police, another was processing the news of the arrest of her friend’s father, and another was witnessing arrests in her neighbourhood right after a communal incident. Some reflected on the horrific incidents that had taken place in the past with some degree of distance from the shock of the moment. In another sense, since our questions were fairly open-ended, people spoke about the political situation and shifted many lenses: at one moment, they were analytical and practical, grappling with how discrimination and violence against Muslims have increased; at another moment, they were in despair, sometimes with a view to the larger situation, sometimes with reference to their own inner turmoil. People spoke about past riots and present demolitions, detailing the betrayals, failures, and difficult moments in their lives. At the very least, we hope that this report can contribute to our understanding of the emotional lives of Muslims in India today.

While we bring to you stories of loss and pain in people’s own words, we struggle to communicate the tone of their voices, the look on their faces, and the tears that flowed down when these experiences were shared. We have tried to remain faithful to the linguistic expressions of the people we spoke to; perhaps what is lost is the pathos and the sadness in their voices, the grief they expressed to us when they put off their Zoom video cameras in order to cry without being observed.

This report is the culmination of longer work done by Bebaak Collective on the question of health and communalism. Previously, we had studied the impact of communalisation of the COVID-19 pandemic on Indian Muslims, with a focus on how access to healthcare was blocked and disrupted by communal violence during the first lockdown. Bebaak, for the last two years, in collaboration with Mariwala Health Initiative, has been working with the Muslim community by providing them with a space to talk about their personal experience with anti-Muslim hatred, build community support, and access mental health services as well.

3. Findings

3.1 Institutional Betrayal

“Mujhe raat mein neend nahi aati. Court website hi dekhta rehta hoon poori raat. (I am not able to sleep at night. I just keep on checking the court website).”

- Bilal, Delhi

Under the electoral and political system dominated by the BJP, the application of the rule of law is contingent upon one’s religion. This “irregular” functioning of the law entails blocking access to legal recourse and accountability, undermining the democratic setup based on a system of checks and balances.36 Muslims in India today are facing an “institutional betrayal,” which is the erosion of reason and expectation from the law i.e. the law will work on universal morality and not on a skewed understanding of “Muslim guilt” and “Savarna innocence.”37 These processes run parallel to the operation of “ethnicised patronage networks,” which work as unofficial state structures to help majority communities secure favours from the government, police, and courts.38

A house being demolished in Khargone, Madhya Pradesh in the aftermath of the Ram Navami violence in April 2022. Source: Scroll.in

To be embroiled in an unfair legal system, trying to prove one’s innocence, becomes an all-consuming affair, requiring one’s constant attention and work. This suffering became apparent when we spoke to Bilal, a 21-year-old student from Northeast Delhi, whose elder brother was arrested in a fraudulent case after the February 2020 pogrom in Delhi. According to the family, Bilal’s brother was recording the rioters burning down his shop, which was used by the police to implicate him in the case. Consequently, he was arrested in 16 cases. The youngest son of the family, Bilal, had to step up, take charge of his family, look after his brother in jail, and fight the legal battle as well.

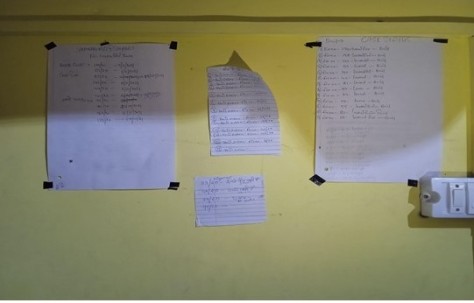

The walls in Bilal’s room were covered with the details of his brother’s case — cases under which he had been charged, updates on the ones he had received bail and the ones they were still fighting to be dropped. It was a glimpse into the extent of Bilal’s worry and inner turmoil, which affected his mental health to the extent that he is unable to sleep at night. He said, “mujhe raat mein neend nahi aati. Court website hi dekhta rehta hoon poori raat. (I am not able to sleep at night. I just keep on checking the court website).”

The wall in Bilal’s room is covered with the details of his brother’s case. Source: Bebaak Collective, April 2022.

Amid the suffering, Bilal still hopes that his brother will return, bringing back the normalcy they had lost due to the riots. “Mere dimaag mein bass yahi hai ki bhai jaldi ghar aa jaye. Phir mummy ka stress bhi chala jayega. Woh sab sambhal lenge. (I hope that my brother will return soon and take care of everything at home. It will reduce my mother’s stress as well).”

This pattern of riot victims being held criminally responsible, leading to a sudden change in the familial dynamics was observed in Khamaria, Raisen district, Madhya Pradesh, as well. Following communal violence between Muslims and Adivasis, a situation has unfolded that lays bare how Muslim women are reeling from the aftereffects of a riot. “Saare mard chale gaye, sirf aurtein bachi hai. (All the men have been taken away. Only the women are left behind).”

The riots took place in April 2022, at the time of Holi, following an incident where a woman from Khamaria was harassed by a group of men, which devolved into a concerted attempt to loot, target, and attack Muslims in Khamaria due to the mobilisation efforts of the BJP and the RSS.39 16 men from the same family living in different households in the village have been arrested and booked by the police.

To accept and come to terms with the absurdity of law, when it decides to go after the ones who have been wronged, is not only to experience the breach of the promise of fairness and justice but also the denial of one’s citizenship and even humanity. Muslims of Khamaria complained that they were denied a fair hearing, “Jiss tareeke se humare saath attyachar hua uska koi rekh dekh nahi hua. Humari koi sunwai nahi hui. (We did not even get to talk about the injustice done to us), referring to the specific targeting of Muslims by the police. Congregated in the veranda of their house, Muslim women described how their fathers, husbands and sons had been taken away by the police under the garb of providing medical help, leaving them alone to handle their households and each other. They cried, “Kya humare pet nahi hai? Kya humare bacche nahi hai jinhe school jana hai? (Do we not have to feed ourselves? Do we not have children who need to go to school?).”

House demolished by bulldozers in Khamaria, Madhya Pradesh, April 2022. Source: Bebaak Collective, April 2022.

Tayyaba, an activist from Shaheen Bagh, spoke about how if the father or the brother in the family is vocal and politically active, the rest of the family is affected when there is a backlash from the state. If the main male member in the family is arrested, there is a huge feeling of isolation and crisis as a protective presence is lost in the family. She spoke about how she had to go to the police station alone when her husband was arrested, and no one stood by her at that moment.

A criminal case requires periodic attendance at the court, regular interactions with the police, and even the perpetrators of the crime that the victim endured. Rashid Ahmed, a teenager from Faridabad, was lynched to death a day before Eid in 2017. His parents and brother have since then fought his case to ensure that the men who killed Rashid face punishment. Rashid’s father, Imran, described the initial interactions with the perpetrators in court where they would raise Jai Shree Ram slogans, and continue to do so even after efforts by the police to stop them. “Humein police protection milti hai court mein bhi. Main phir bhi apna chehra dhak leta hoon. (We get police protection even in the court but I still cover my face).”

A family from Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, whose son Aslam, was targeted by Bajrang Dal members, following a casteist remark, “tum log basaate ho (you people smell),” recounted the repeated horror of facing violence from a mob as well as the police and village authorities. Aslam was accused of trying to remove the deity from the temple and forced to chant Jai Shri Ram. Aslam’s father told us how they managed to run from the forest to the police station to file their complaint where they met with another form of aggression, i.e., police brutality. “Hum jungle chale gaye the bachne ke liye. Dehshat baith gayi ki phirse maar ho jayegi. Bahu beghair saree ke daudi. Motorcycle pe gaye FIR likhne. Station pe bhi maar peet ki. Humse police nahi mili aur humari report nahi lee. (Our daughter-in-law was forced to run without her saree. We went on the motorcycle to the police station where they beat us up again. The police did not listen to us, and they did not file our report).”

Both the police and sarpanch had told Aslam’s family to leave the village if they wanted to save their lives. “IO sahab ne humein kaha ‘tum log yahan dikhne nahi chahiye. Idhar dikhna nahi chahiye, woh maar daalenge. (The IO told us that we should not be seen in the village. If we do, they will kill us).”

While Aslam’s bail is still pending, the family’s constant displacement from their home and village, followed by a month-long stay at a hospital in Sagar, and the ongoing police harassment have taken their toll. Aslam’s mother-in-law, who moved in with her daughter to help out the family, spoke about how the violence meted out at the hands of the police robbed them of the right to be heard, to present their grief in public. It is a testament to how the legal system is reduced, for Muslims, from a concrete means of ensuring their dignity and rights to a mere “spectacle.” She said, “Hum apna dukh na haspatal mein bata sake aur na police walon ko. (We couldn’t even talk about our pain with the doctors or the police officers).”

3.2 Financial worry and setback to social mobility

“Musalman aur kamzor samajh kar humare saath log dhokha karte hai. (They see our Muslim identity and weak status and think it’s okay to cheat us financially).”

- Abid, Uttar Pradesh

During our interviews, the search for a vocabulary to describe the internal struggles and worries of a family, in the aftermath of communal targeting, often began and ended with their financial problems. To recount and narrate the trajectory of their financial collapse was part of their struggle to rebuild their lives, reconfigure everyday life to make it more habitable, and understand the extent of loss suffered by them. In many cases, a sudden change in the family’s financial situation had shaken their sense of material and mental security. For others, communalism has fundamentally changed what they consider as attainable for creating a stable future for themselves.

The shock of financial loss

For the Muslim family in Khamaria, Madhya Pradesh, the threat of murder—“agar yahan aaoge toh aapke payr kaat diye jayenge, yahan se zinda nahi jaoge wapis (if you come here, we will break your legs and ensure that you won’t leave alive)”—was used to intimidate them from taking their share of money and equipment from their land. Houses and two Muslim-owned shops were demolished by the state authorities after the riot in Khamaria, continuing a pattern of “bulldozer politics” wherein people’s homes, means of livelihood, and security are destroyed, through the public performance of punishment, before any formal indictment. The stress of handling the financial future of the family is an overriding concern for the women of the family as they are unable to travel outside their village for work. Since the two shops owned by the family were bulldozed they have been unable to repay their previous loans. This crisis has been aggravated by the fact that the men, usually responsible for handling such decisions, have been arrested. Rukhsana, the daughter-in-law, described this unexpected change in familial responsibilities. “Jo sochne wale the unko le gaye. Jo humare saath ho raha hai seh rahe hai aur jo hone wala hai usko bhi bardaasht karna padega. (We are surviving on the savings that we have accumulated over the years. The men who used to think and worry about these things have been taken away. We have endured so much and will have to tolerate a lot more of what is going to happen).”

Abid, an elderly daily wage worker from Uttar Pradesh, lost his son, Naseem Ajmal, to an incident of mob lynching. Naseem was lynched to death by a vigilante mob of around 250 people, led by a local Shiv Sena group under the suspicion that he was involved in cattle trading. Naseem was the eldest son and the breadwinner of the family. The burden has now fallen on Abid, to provide for the entire family. Carrying out his work has become increasingly difficult because of the anti-Muslim hatred he has had to face at every step. While travelling to Srinagar, Himachal Pradesh along with thirty other Muslim men for work at the time of Bakra-Eid, a drunk man stopped and abused them with derogatory terms. He said, “Humari daadhi aur topi ko dekh ke, usne wohi bhasha boli jo sarkar bolti hai. (He used the same derogatory language used by this government after looking at our beards and religious garments).” He spoke about how even though it was one man abusing a large group of thirty people, no one said a word, and they were compelled to sit back quietly in the bus, due to the fear of retaliation.

In another instance, Abid had provided labour worth Rs. 15 lakh by bricklaying a building but was denied the money owed to him. Abid described that after his son’s death, who had been his pillar of support, people found it easier to ignore and reject his demands. “Musalman aur kamzor samajh kar humare saath log dhokha karte hai. (They see our Muslim identity and weak status and think it’s okay to cheat us financially).” The graded suffering and living on the brink of poverty, after losing a young earning male member, came out most strongly in this discussion.

Mohammad Shamsul was brutally shot by the police during the state’s eviction drive on September 23, 2022, in Dhalpur, Assam. Shamsul’s wife, Safeena Ibrahim, gave us short answers regarding how she has been coping after her husband’s death. The difficulty in broaching a topic of personal loss and grief became clear in our interaction with her. She was dealing with not only the recent nature of the incident but also the sheer enormity of state violence in destroying her home and family. Safeena also gave us short answers about her medical condition, her children’s schooling, and her maternal family’s whereabouts, all the while trying not to break down while talking. The details of one’s immediate survival were easier to recount and explain, and to a certain extent, even to enquire about as a researcher or social worker. Waseem, a villager who was shot in his leg during the eviction drive, explained her condition since she neither received government compensation nor support from her own family. “No matter how close, she has been married off. The responsibility is no longer theirs. They don’t have land, like us. They do daily-wage labour to survive. They are trying to look after themselves. It has been hard for her to manage. She cannot do labour and has three children to look after.”

The rebuilt houses of Dhalpur, Village 1, Assam. Source: Bebaak Collective, May 2022.

Bilal, whose shop was burned down following the Delhi pogrom, described how the incident had robbed their house of its erstwhile joy—earlier, there was a “raunak” or spark in their house as they would keep bringing food items and snacks from the shop. “Ab kiraane pe jaane ka mann bhi nahi karta hai. Apni dukaan ki bahut yaad aati hai, (I do not feel like going to the place where our shop was. I miss it too much),” Bilal added as he tried to explain the ease with which they had previously lived. His mother also explained, “Paise ab seene se laga ke rakhte hai. Hamari khuraak pe bhi asr pad gaya hai. (We are very careful with money now. It has affected how much we eat).”

Of changed dreams and aspirations among Muslim youth

The loss of opportunities due to a riot not only limits the economic prospects of families but also changes people’s aspirations, dreams, and hopes for social mobility. Bilal had planned to pursue a career in medicine in Delhi, but due to the pogrom, he had to miss his class XII board exams. He is 22 years old now and trying to finish school while also planning to pursue a computer course to support his family.

A sense of loss of prospects for upward mobility was communicated by the eldest son of the family in Khamaria, MP, who was pursuing his studies in Indore before the riots. He was unable to continue his education due to the fear of leaving his home and the additional familial responsibilities. His sister-in-law, Rukhsar, whose husband has been arrested, pointed out how the experience of witnessing her family members being wrongfully arrested changed her daughter’s desire to become a police officer. “Usne dekha ki police wale kaise humein pakad pakad ke le jaa rahe hai toh woh boli ki police wali toh nahi banoongi, (She saw how the police arrested innocent people after the riot. Now she doesn’t want to become a police officer),” Rukhsana explained while referring to her daughter.

For activists like Sumaira, studying at Aligarh Muslim University and witnessing the backlash against her friends like Afreen Fatima, has shaken her belief in the capacity of a legal career to enact social good. She had decided to study law to become a good lawyer and help people. With the higher judiciary remaining silent about the ongoing atrocities, she feels a sense of helplessness and questions, “Police aapke saath nahi hai, court kuch stand le sakte the par unhone liya nahin. Mujhe samajh nahi aa rahi main ye padhai kyun kar rahi hoon. (The police do not support Muslims while the court has chosen not to take a stand. I don’t know why I am doing a law degree in this situation).”

Sumaira pointed towards an impossible struggle facing Muslim youth, wherein they have been forced to deal with how the ruling regime has taken away their freedom to wear clothes or eat food of their liking. There is a lack of space in the current scenario even to ask questions and think about what they want to do in life.

The police attack on Jamia students in December 2019, combined with the negative media portrayal of the university, has discouraged Muslim parents from sending their children to Jamia Millia Islamia University, according to activist Tayyaba. Despite the academic credentials of the university, the parents’ fear that their children will be targeted due to their association with Jamia has led many of them to cancel their children’s admission or prevent the latter from travelling to Delhi to study at the university.

The sudden change in a family’s fortune is a reflection of how communal violence is also geared towards economically disempowering Mulims,40 in addition to widening social divides. In each case, the loss of a family member was followed by stigma in the workplace and job market, making it even more difficult for them to rebuild their lives. Muslim youth are also being forced to change their career plans in the face of difficulties at home and in educational institutions and workplaces due to widespread communalism.

Muslim students in Karnataka denied entry into IDSG Government College, Chikmanglur due to the institution’s discriminatory policies towards hijab wearing students. Source: The Cognate.

3.3 The physical toll of loss and death

“Meri dhadkan khatm ho gayi hai. Sar aur chest mein hamesha dard rehta hai. (I find it extremely hard to breathe. There is a constant pain in my head and chest these days).”

– Farhad, Delhi

The experience of illness is narrated not just through a list of symptoms but also as part of our everyday lives. Making sense of one’s physical illness entails reflecting on events that fundamentally altered the quality of one’s life.41 We observed that in several interviews, the onset of chronic weakness, physical injury, impairment, and death were all explained as part of the experience of being a victim of communal violence. Bilal told us about his father’s death, which took place six days after his brother’s arrest, “Bhai ke arrest ke sadme ki wajah se abba khatm ho gaye. (My father passed away due to the shock of my brother’s arrest).” His mother is now bedridden, unable to leave home and take up any kind of household chores, while Bilal has taken certain steps to cope with the stress of his responsibilities. “Pathri ke liye ek capsule hoti hai. Wohi leta rehta hoon. Lat si lag gayi hai. (It has become a habit of mine to keep taking pills meant for kidney stones).

The grief over the loss of their child took a physical toll on Hamid’s father, who suffered a major heart attack after his son’s death. Hamid’s father broke down while trying to talk about the attack, an indication of how difficult it was for him to deal with the violent nature of his child’s death. The medical procedure added to the family’s debt as they had to sell three plots of land to fight their son’s case in court. Shameem, Hamid’s brother, who suffered serious injuries during the communal attack is unable to secure employment because of his physical disability. For his mother, Farhad, the incident has caused permanent damage to her body, “Meri dhadkan khatm ho gayi hai. Sar aur chest mein hamesha dard rehta hai. (I find it extremely hard to breathe. There is a constant pain in my head and chest these days).”

The loss of family members to communal violence, therefore, is not just a singular event involving the violence inflicted by vigilante mobs or the state’s heavy hand, but an ongoing crisis that consumes and affects people in various ways. Naseem’s mother was unable to come to terms with the tragedy of her son’s death seven years ago. We were informed that she had “gone mad” (“mummy dimaaghi rukh se pagal ho gayi hai”). Naseem’s sister spoke about the erratic changes in her mood, “Kabhi bahut gussa karti hai, kabhi normal rehti hai. Subah mein chali jaati aur shyaam mein wapis aati hai. Do teen din tak khana nahi khaati. (Sometimes she is fine and other times she gets extremely angry. She leaves the house in the morning and comes back in the evening. Sometimes she goes 2-3 days without eating).”

Initially, when she heard the news of her son’s death, Naseem’s mother refused to speak for six days. It was the nature of her mourning—a complete reversal from her usual state of being social and regularly engaging in household chores. Her husband, Abid, spoke about the pain of watching her grieve in a way that detached her from the rest of the family, “Kisi se baat nahi ki. Woh bass roti rahi. Na keh ke roi, na bol ke roi, bass aasu tapakte hue dikhe aur kuch nahi. (She did not speak to anyone. She simply wailed and shed tears; she did not even cry with words).” When asked about pursuing mental health treatment, the family spoke about their complete lack of funds. Abid, the sole earning member of the family, has been unable to manage his wife’s reaction to their son’s death. He spoke about the huge responsibility on his shoulders: doing hard wage labour to continue feeding his family, paying the medical bills of one of his daughters who suffered from severe tuberculosis, and the pending marriage of his third daughter. Amidst these concerns for basic survival and sustenance, his wife’s mental health was not seen as a pressing need and accepted as a natural and unfixable part of their lives. Being denied the usual course of diagnosis and treatment, and forced to put together the pieces of their lives destroyed by cow vigilantism, is an example of how Muslims face discrimination within the health sector and how their suffering is made acute because of their socio-economic backwardness.

The impact of political violence escapes an easy explanation of the loss of one’s physical health, leading to increased personal suffering and pain, because it also changes one’s strength as a citizen. Asghar, an activist from Shaheen Bagh, raised a unique and important point about the relationship between having a healthy mind and the ability to protest. In order to protest, to talk about what is acceptable and what is not, and to raise one’s voice, mental health is necessary: the strength to understand and think about the situation. He believed that at least 70 per cent of people in the community needed to have a healthy mind in order for the community to be mobilised politically. The government, however, is making every possible effort to break this ability through the explicit alienation and othering of Muslims.

Individual strength is derived from, and impacted by, the level of social and political support a community receives. Aslam’s father, from Sagar, Madhya Pradesh, had to be hospitalised for a month due to the injuries inflicted by the Bajrang Dal mob. His family of five, after being forced out of their village, stayed with him in the hospital for that time period. The ability of the hospital to accommodate them and not adopt a hostile attitude, went a long way in helping the family find a footing after being displaced from their home.

3.4 Fear and Hypervigilance

“Chaar saal ho gaye mujhe bazaar gaye huye. Wahan main pehle 24/7 wohi baitha rehta tha aur 12 baje ghar aata tha. Meri tabiyat ab wahan lagti hi nahi hai. (It has been four years since I have been to the market. Earlier, I used to sit there the whole day. I just don’t feel like going there any more).”

- Rashid, Delh

The continuous nature of trauma often changes the victims’ everyday lives and interactions, reproducing its effects in how they interact with the world, primarily through their religious identity and their decisions about where and how they choose to travel, whom they sit down with, and how much and with whom they speak. The core beliefs of victims are transformed, increasing their watchfulness and susceptibility to anxious thoughts as their trust in a predictable and peaceful world is disrupted by communal violence. 42

Police attacked civilians during the anti-CAA-NPR-NRC protests in Kanpur, December 2020. Source: The Wire.

Restricted mobility of Muslim women

The situation of a riot leaves scars in the form of hypervigilance, i.e., being in a state where the victims anticipate more violence and lose faith in a promise of a return to normalcy where the heightened sense of alertness and anticipation of violence itself becomes the new normal. The riot is communicated and registered as a warning in the speeches of political leaders and right wing social media posts — this can happen again. In the case of the women, who were collected from different houses and locked away in one place during the riot in Khamaria, this vigilance takes the form of closing themselves off and restricting where they travel, while still grappling with the pressing concerns of money and caring for their children and relatives. “Log bahar se aak dange karke chale gaye, hum isse abhi bhi jhoonjh rahe hai. (It was so easy for people from outside to cause riots in our village. Now, we have to deal with its consequences).”

In a riot, sexual violence is a looming threat for women. The experience of finding themselves at the mercy of a violent crowd haunts them as it continues to shape their social interactions and mobility post-riot. Women recalled how the crowd had threatened them, saying, “keh rahe the ki ladies aur bacchon dono ko mat chodo. (The rioters said that they will not spare even the women and children).” The “carnivalesque aspect” of a rioting mob,43 recently seen in the spectre of sword wielding crowds dancing to Islamophic music, slogans and chants during Ram Navami, has a particularly devastating effect on women as it rekindles memories of violence.44 They recounted how the rioters, coming from the adivasi villages, asserted their Hindu identity, “Humein kam mat samajhna. (Don’t think that we are any less than Hindus).” The women of the family, involved in the initial conflict, have become fearful of stepping out of their homes.

The restricted mobility of women due to the fear of violation in riots came up regularly in interviews. Zebunissa, Naseem’s youngest sister, was forced to leave school after her brother’s death. She was in the seventh grade, and was unable to complete the half-yearly exams due in the private school she attended. Neither Zebunissa nor her elder sister do any kind of work outside of the house. They sew at home and manage the household, while the elder sister waits till there is enough money for her marriage. Some girls in their area do have jobs, but a sense of fear about their safety and their religious identity have prevented their father from sending them outside the house.

Sumaira, an activist from Aligarh Muslim University, argued that the curbing of the freedom to practise religion or prohibiting the wearing of the hijab had led her parents to restrict her movement outside the house. The threat of violence within a volatile communalised atmosphere has restricted women’s mobility to a great extent. Earlier, she said, women weren’t allowed to leave the house due to patriarchy; now, even if they want to do anything like work or study, the lack of social safety restricts them. The sexualisation of Muslim women within the Hindu nationalist imagination, with its manifestation in both online and offline violence, 45 has exacerbated the control over their bodies and the forms of unfreedom experienced by them within familial structures. The intersection of patriarchal and communal violence has also amplified the securitarian discourse46 that seeks to limit women’s mobility and participation within the public sphere.

Of isolation and abandoned social practices

Rashid’s father used to visit his local bazaar regularly to decompress after work and meet his friends and neighbours. After his son’s violent death, he has stopped these daily visits, “Chaar saal ho gaye mujhe bazaar gaye huye. Wahan main pehle 24/7 wohi baitha rehta tha aur 12 baje ghar aata tha. Meri tabiyat ab wahan lagti hi nahi hai (It has been four years since I have been to the market. Earlier, I used to sit there the whole day. I just don’t feel like going there anymore).”

He added that ever since they have been provided with police protection, they prefer not to travel without it, saying, “Hum ab police ke bina kahi niklate hi nahi hai. Humko wakil ne keh diya hai ki apne beton ko nikalne mat dena. Aisi dehshat baithi hui hai. (We have been given strict instructions by our lawyer not to allow our sons to go out alone. The fear is so much that we never leave the house without police protection).” Since Rashid was attacked in a local train, there is now a reluctance to use it. His brother spoke about how they are forced to take the metro or travel by car.

Zeenat, an activist from Lucknow, witnessed the police attack her family during the crackdown on activists who were a part of the anti-CAA-NPR-NRC movement. Zeenat had been active with the ghanta ghar sit-in in Lucknow and involved with the larger feminist movement. The visual of the day when her father and brother were beaten up in front of her eyes and arrested by the police, her sisters were made to run on the road, and the neighbours came together on the streets to witness the scene of police brutality, has stayed with her. Even now, slight and sudden movements and unexpected noises remind Zeenat of that day. If someone shouts, shuts the window with force, knocks on the door or repeatedly rings the bell, she is immediately transferred to that day, “Ek dum se dil kaanp jaata hai ki kuch ho gaya ya kuch hone wala hai. (It fills me with so much fear. I feel as though something bad is going to happen again).”

As a result of our interviews, we were able to see how, when a seemingly routine day can turn catastrophic, resulting in the loss or arrest of loved ones, the memory of that day (specifically, the fear or dehshat induced by it) continues to shape the lives of victims and family members.

3.5 Losing community, neighbours and friends

“Mere sanghathan aur bhi mahila sanghatan mein logon ne dekha magar kisi ka koi response nahi tha. (People from my organisation and other social rights organisations saw what happened to me but never reached out).”

– Zeenat, Uttar Pradesh

A disruption in relations with people who occupy our everyday emotional and social lives is a feature of “institutionalised everyday communalism,” wherein instead of consequent healing and rebuilding of relationships, a “new normal” characterised by betrayal and mistrust is created. In addition to a communal event altering relations within a community of people, the general feeling of distance from one’s acquaintances and friends is also being observed. Shamima used the word “betrayal” to encapsulate the experience of Muslims in India, wherein they are witnessing their friends, neighbours, and colleagues showcasing their support for right-wing politics. The hurt of this experience is accentuated by the espousal of anti-Muslim politics by one’s friends, co-workers, neighbours, and acquaintances. Their political beliefs translate into a world view, which closes the distance between one’s friend and the stereotype of a “Muslim,” provided by this political (mis)understanding. Therefore, friends and neighbours disappear in the face of a hateful image of the Muslim “other.”

Residents of Jahangirpura, a Muslim dominated neighbourhood, which faced demolition drives after the Ram Navami violence in April 2022. Source: Article 14

The experience of Muslim girls in Karnataka, whose right to education was curbed by the school’s decision to ban hijabs in the classroom, brought this out very clearly. 47 They witnessed their friends and classmates turn against them, participating in rallies where they wore saffron scarves and mocked, shamed, and bullied them for refusing to back down and choosing to continue wearing their hijab. Shamima explained this situation when she spoke about her own Muslim clients: “People talk about the disappointment with friends, losing relationships and not even having the space to grieve that relationship because the people that they had to end relationships with are avid hate mongers. I have also lost so many friends because of this.” She shared her own loss of many friendships and the dissonance that is felt in relationships: at one end, feeling the extreme urgency of feeling a threat to one’s life due to one’s Muslim identity, and at the other, having Islamophobia dismissed as a real issue in the country.

Sayeda Zainab, an activist who was imprisoned because of her role in the organising anti-CAA-NRC movement and is now out on bail spoke about how her family’s support was a significant factor that helped her during and after her incarceration. However, the turning back of both her childhood friends and progressive community, deeply disappointed her. She spoke about a betrayal from the “so-called progressive people in the country” that she felt along with many other young people in her circle. In comparison to the farmers’ movement, she observed that the anti-CAA, NRC, NPR movement did not receive the same kind of support. The feeling of betrayal also comes from the way people in general from the majority community have become insensitive to the suffering of Muslims and do not react when Muslims are particularly targeted. She was forced to realise the differential treatment on the basis of her identity, she compared the response to her arrest, to that of activists from the majority community. Her minority identity and the place of her birth (Kashmir) enabled a profiling of her that was not possible for other activists involved in movements.

Zainab spoke about how initially, after her release, many people she knew would not interact with her. On top of that, due to the UAPA case against her, any of her friends could be witnesses against her; therefore interacting with anyone could amount to intimidating or pressuring a witness. She described the grave sense of fear among students in Jamia during that period due to different intimidation tactics by the state. Students were called for questioning, their families were harassed, and they were pressured into making false statements. Losing her friends from the majority community who come from a family of BJP supporters was a shocking and painful experience, during a difficult time in her life.

Although Shaheen Bagh received a great deal of popularity during the anti-CAA movement, to the extent of becoming a symbol of protest and a household name, activists involved in the movement did not feel like they received support after the events of February 24, 2020. By the 24th, riots had broken out in North-East Delhi, and a long period of harassment of Muslim activists began from arrests, to police harassment to legal harassment.

An activist who had been slapped with several cases after the Delhi riots due to his activism in Shaheen Bagh spoke about his harrowing experience. Even though it was such a large movement, and many groups, political parties, and lawyers had promised help and support, those promises remain painfully empty. He spoke about how he had to fight everything on a personal level, the limits of peoples promise became evident after the riots. People disappeared when the crisis reached his doorstep: his parents in UP were harassed, he was slapped with several cases under the National Security Act (NSA), and the police turned up at his house every time there was any kind of political activity in Shaheen Bagh.

Zeenat also expressed disappointment with her own organisation and its members who had failed to reach out to her and extend their support and solidarity during her father’s arrest. She said, “Mere sanghathan aur bhi mahila sanghatan mein logon ne dekha magar kisi ka koi response nahi tha. (People from my organisation and other social rights organisations saw what happened to me but never reached out).” Her anger was directed towards the established members of the progressive community who still failed to speak up for her, “Agar itne established log darte hai toh phir humein kyun aage karte hai? (How do such established people expect us to lead the movement when they themselves are so scared?)”

Zeenat also described how she felt guilty about her family’s suffering as everyone around her blamed her, her work and her activism,“Ye itna zyada feel ho raha tha ki agar meri wajah se hua toh mujhe kyun nahi le ke gaye, papa ko kyun le gaye? (I felt that if this was happening because of me, why didn’t they arrest me? Why did they go after my father?)” She now feels there is need to be careful since the fight against the state will be a prolonged one, requiring both commitment and deliberate, calculated action.

The Bhopal-based activist, Shama, who had visited the family in Sagar when Akram was undergoing treatment for his injuries, pointed out how there is a lack of political mobilisation from even within Muslims when it comes to Pasmanda Muslims, increasing their feeling of abandonment and isolation, “They wear sarees and bindis and don’t look or speak like typical Muslims. It’s easier for activists and organisations to ignore their cases.” A simple Hindu-Muslim binary cannot explain the violence faced by Pasmanda Muslims. A complex layer of casteism and communal violence has disrupted their access to avenues of formal justice as well as community support.48

3.6 Hope for a political future

“We are reminded on a daily basis that our voice and existence is illegal, there is no one to go to for help. I don’t have words to express, I’m not able to react. How do I tell you what is happening and what will happen in the future?”

- Sumaira, Uttar Pradesh

The precarious future of Muslim children

Tabassum and Mariam from Shaheen Bagh, expressed their fears regarding the impact consuming media had on their children. From seeing images and videos of violence against Muslims to listening to the anti-Muslim national discourse on television, they spoke about how their children’s lives were mediated by these devices, and how they were influenced by them. For example, their children saw videos of the police backlash after some Muslim youth took out a rally for jumma; they saw the extreme violence handed out to men not very much older than them. What would be the long term effects of seeing a discourse full of hatred and images of violence on the younger generation? This was a recurring anxiety articulated by the women activists.

Another more general concern expressed by the group of activists from Shaheen Bagh, was of the future lives of the next generation. According to them, they had seen relatively good times. As parents, they felt that the future in India was bleak, with meagre prospects for Muslims.

Rehmat, a Baroda-based activist who works with Muslim women, spoke about her experiences in Gujarat since 2004, when she first became involved in community organising. She shared how communal violence occurring in other regions has instilled a sense of dread that it may occur in their community as well. How they will cope if something were to happen to them is a pressing anxiety for the people with whom she works. Rehmat spoke about the fear she experiences and how those around her share the same thoughts and worries. She said that young people felt frustrated as they are unable to comprehend what to do or how to improve the situation.

Tasleem, an activist from Saharanpur, Uttar Pradesh, spoke candidly about the political climate in her region. As she spoke to us, arrests were taking place in different parts of UP in response to a religious rally held on Friday after namaaz in protest agaisnt Nupur Sharma’s remarks about Prophet Mohammed. While Tasleem spoke to us, she conveyed an acute sense of fear and uncertainty that was close at hand. She informed us about the mass arrests of youth in her town, including those who had not taken part in the rally. She spoke specifically about the arrests of young Muslim men and the police brutality and violence inflicted upon them. In addition to arresting and physically torturing young Muslim men in Saharanpur, the police had also initiated a demolition drive, which was underway when we met with Tasleem. Faced with increasing state repression, difficulties in securing FCRA (Foreign Contribution Regulation Act) for several NGOs,49 and the threat of violence, activists are constantly worrying about sustaining their work and mobilising the political community to build a strong resistance movement.

Cultivating hope: What is to be done?

Jamia students at the helm of anti-CAA-NPR-NRC protests held in December 2019. Source: Shethepeople

The smallest mistake or digression by a member of the Muslim community is met with a response that is blown up in proportion to the crime. The government waits for the community to make a mistake and responds with aggressive tactics such as bulldozing homes. People are tortured and jailed at the smallest perceived “mistake.” The pattern of targeting the Muslim community in the form of organised riots has now taken the form of attacks on individual Muslims, journalists, and activists. The cumulative impact of individual cases of Muslims being arrested and jailed under stringent laws has been to completely silence the community. This was echoed by the activists from Shaheen Bagh, who said that the mental pressure of witnessing all this has caused the community to become quiet, with many ceasing to respond to the situation.

Frustration, pressure, and a sense of helplessness also accompany many of the activists we spoke to. What can be done in this situation is a pressing question asked with desperation and a need to act, albeit without clear paths of struggle ahead.

Rehmat highlighted how, before, the support of the police in filing FIRs would be taken for granted, but now that it has disappeared, avenues for justice seem non-existent. She spoke about how activists like her all faced the same question: How do we bring about a change in this situation? Even after filing FIRs and taking issues up at the national level, the communalised atmosphere seems to be deteriorating rapidly. If they raise the issue of communal riots with the police, they are told to go to Pakistan. She attributed this mentality to 25 years of the BJP’s rule in Gujarat.

Tasleem spoke about not only a general sense of fear, but also her own personal fear as an activist living in a Muslim majority neighbourhood in town. She confided in us that she was living with her mother for the past three days due to the dread of her impending arrest. There were arrests and campaigns happening as we spoke. She was terrified at the thought of returning home and told us that she was unsure of the consequences. The situation, she said, created a lot of stress and tension in her mind.

Sumaira, evaluating the situation wherein her friend’s childhood home was destroyed by the Uttar Pradesh government, spoke about a strong feeling of despair and helplessness: “We are reminded on a daily basis that our voice and existence are illegal; there is no one to go to for help. I don’t have words to express myself; I’m not able to react. How do I tell you what is happening and what will happen in the future? I’ve lost the words to react. How do I help another person; tell them to remain brave, tell them that we have to come out on the streets and fight back; how long do we keep telling people to be brave and give them solace; how long can I wait till things get better? Because nothing is getting better.”

The sit-in at Shaheen Bagh, Delhi, January 2020. Source: Indian Legal

Emphasising a vacuum in terms of political leadership, Humayun, an activist from Maharashtra, talked about the silence of forty-four elected Muslim MLAs in UP. Their inability to use their political position to highlight violence against Muslims was striking; he felt that their active opposition to the current regime could have made a difference. He observed that the religious leaders of the community were solely mobilised on questions of “mazhab,” or religious articulation of Muslim identity, and had no concrete solutions to the deteriorating situation. The BJP and the RSS, on the other hand, have a very concerted agenda. In this scenario, he raised the question of what a common person could do. With the government dismantling organisations and attacking activists, he said the common man could do nothing but pray. People look for some kind of “tasalli” or solace in their lives and have no option but to wait for God’s intervention.

Still, Humayun felt that activists must try to find areas of possible intervention, even if those areas seem very few; if defeat is accepted, “then everything will be over for us.” He also talked about the need to study the resistance tactics of anti-apartheid activists and Jews in Nazi Germany to find new ways of opposing the government.

4. Conclusion

Our findings show that the experience of health, in its physical and mental manifestations, is politically mediated. Undergoing an episode of communal violence fundamentally alters the quality of one’s life. We observed that it changes priorities in education and career as well as the mental stability of people. The unfair judicial system, especially for Muslims, has left them with a sense of hopelessness, stealing from them the right to think and plan about their futures. The role played by the absence of an unbiased, independent judiciary in cultivating and fueling this hopelessness speaks to the significance of the institution in acting as a balancing force against the authoritarian policies of the government.

The cascading effects of financial ruin and a severe decline in physical health due to anti-Muslim hate were noted in several interviews. The loss of community severely affects one’s sense of confidence and surety about navigating a difficult situation of legal cases or simply rebuilding one’s life after a violent incident. We found that the persistent question of building politically viable options for Muslim youth, wherein they are able to access state institutions without the fear of being targeted, is something that has preoccupied the minds of several Muslim activists.

An all-pervading sense of being made to feel powerless in front of a fascist state and hateful ideology, which has forced several Muslim victims of communal violence to change how they live their lives, is the most important point that has emerged from our work. It is in these small changes as well as the more overt forms of deterioration in physical health and financial or material loss that the mental health of Muslims needs to be evaluated and located.

5. Recommendations

The mental health problems faced by Muslims can be addressed by mitigating the harm created by an increasingly communal social, political, and economic landscape. The role of civil society is crucial in ensuring that the legal system is held accountable for its treatment of Muslim victims of hate crimes. They also need to act as watchdogs by creating pressure on authorities to take appropriate action against instigators and perpetrators of communal violence.

The National Human Rights Commission and the National and State Minority Commissions can play crucial roles in supplementing police investigations into cases of communal violence through their own mechanisms of inquiry and ensuring that a fair hearing is afforded to victims. It is extremely critical that the state governments provide compensation to victims of hate crimes.

The experiences of people interviewed for this report have also shown the importance of civil society organisations in providing emotional support and community strength to victims. Grass roots organisations, women’s groups, and other civil society groups need to actively engage with victims of hate crimes by providing them with solidarity to counteract not only the stigma often attached to victims but also to create a safe space for them to unburden themselves and seek support.

At the level of law, a more comprehensive set of efforts by the state, judiciary, media, and multiple stakeholders is needed to address the issues that Muslims face. An anti-discrimination law—recognising the multiple and intersecting forms of oppression—is required to register the various forms of hate crimes committed against minorities in India.

Given the deep psychological impact of growing communalisation, trauma care centres and counselling services for Muslims should be made available at the local and district levels, as well as in Muslim-concentrated areas where access to healthcare is especially restricted. Training given to health care workers needs to include information on dealing with people who are victims of hate crimes and communal riots in order to provide treatment based on the principles of non-discrimination and equity of care.

Mental healthcare workers should adopt and push for a different approach in their practice that prioritises an understanding of the effects of class, caste, and religious markers on a person’s well-being. Mental health practitioners also have a responsibility to further investigate and research the trauma caused by identity-related violence. They need to ensure a more robust and active implementation of the stipulations of the Mental Health Care Act, 2018, which states, “There shall be no discrimination on any basis including gender, sex, sexual orientation, religion, culture, caste, social or political beliefs, class or disability.”

Endnotes

- Gupta, Ashish and Diane Coffey, “Caste, Religion, and Mental Health in India,” Population Research Policy Review 39, no. 6 (2020): 1119-1141.

2. Farooqui, Neelo and Absar Ahmad, “Communal Violence, Mental Health and Their Correlates: A Cross-Sectional Study in Two Riot Affected Districts of Uttar Pradesh in India,” Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs 41, no. 3 (2021): 510-521.

3. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), “Kashmir Mental Health Survey,” Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (IMHANS), University of Kashmir, 2015, https://msfsouthasia.org/sites/default/files/2016-10/kashmir_mental_health_survey_report_2015_for_web.pdf (accessed on November 29, 2022).

4. Interview with Dr. Samah Jabr, https://qz.com/1521806/palestines-head-of-mental-health-services-says-ptsd-is-a-western-concept (accessed on November 28, 2022).

5. Kleinman, Arthur, Veena Das, and Margaret M. Lock eds., Social Suffering (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

6. Sircar, Oishik, “Spectacles of Emancipation: Reading Rights Differently in India’s Legal Discourse,” Osgoode Hall LJ 49, no. 3 (2011): 527-573.

7. Chandra, Rajshree, “‘Extraordinary’ laws are becoming central to the politics of repression in India,” The Wire, August 28, 2018, https://thewire.in/rights/extraordinary-laws-are-becoming-central-to-the-politics-of-repression-in-india (accessed on October 22, 2022).

8. Verghese, Leah, “NCRB 2019 data shows 165% jump in sedition cases, 33% jump in UAPA cases under Modi govt,” The Print, October 12, 2020, https://theprint.in/opinion/ncrb-2019-data-shows-165-jump-in-sedition-cases-33-jump-in-uapa-cases-under-modi-govt (accessed on October 24, 2022).

9. Manral, Mahender Singh, “Mohammed Zubair, AltNews co-founder, arrested for allegedly hurting religious sentiments,” Indian Express, June 28, 2022, https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/altnews-co-founder-mohammad-zubair-arrested-by-delhi-police-7994635/ (accessed on November 27, 2022).

10. Patel, Aakar, “Book Excerpt: The Many Anti-Muslim Laws Brought in by the Modi Government,” The Wire, November 12, 2021, https://thewire.in/politics/price-of-the-modi-years-book-excerpt (accessed on November 27, 2022).

11. Dash, Sweta, “Behind The BJP’s 2-Child Policies, An Anti-Muslim Agenda that will Endanger All Indian Women,” Article 14, September 8, 2021, https://article-14.com/post/behind-the-bjp-s-2-child-policies-an-anti-muslim-agenda-that-will-endanger-all-indian-women–613823097d3c5 (accessed on November 28, 2022).

12. Jayal, Niraja Gopal, “Reconfiguring Citizenship in Contemporary India,” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 42, no. 1 (2019): 3- 50.

13. Parashar, Utpal, “Over 19 lakh excluded, 3.1 crore included in Assam NRC final list,” Hindustan Times, June 24,2020, https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/assam-nrc-1-9-million-names-excluded-from-final-list (accessed on November 30, 2022).

14. Gowen, Annie and Manas Sharma, “Rishing Hate in India,” Washington Post, October 31, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2018/world/reports-of-hate-crime-cases-have-spiked-in-india/ (accessed on November 30, 2022).

15. Bhat, Mohsin Alam, “‘The Irregular’and the Unmaking of Minority Citizenship: The Rules of Law in Majoritarian India,” Queen Mary Law Research Paper 395 (2022): 1-37, https://ssrn.com/abstract=4274814 (accessed on November 20, 2022).

16. Staff Reporter, “Gregory Stanton Warns, ‘India Is On The Verge Of Genocide Against Muslims’,” ENewsroom, September 7, 2022, https://enewsroom.in/genocide-against-indian-muslims-gregory-stanton/ (accessed on October 20, 2022).

17. Jaffrelot, Christophe, Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007).

18. Chander, Mani, “The Rising Intimidation of India’s Muslims & The Criminalisation of Eating, Praying, Loving & Doing Business,” Article 14, September 16, 2022, https://article-14.com/post/the-rising-intimidation-of-india-s-muslims-the-criminalisation-of-eating-praying-loving-doing-business- (accessed on November 22, 2022).

19. Jaffrelot, Christophe, Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021).

20. Pai, Sudha and Sajjan Kumar, Everyday Communalism: Riots in Contemporary Uttar Pradesh (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018).

21. Raj, Kaushik and Alishan Jafri, “As Hindu Extremists Repeatedly Call For Muslim Genocide, The Police Ignore An Obvious Conspiracy,” Article 14, January 10, 2022, https://article-14.com/post/as-hindu-extremists-repeatedly-call-for-muslim-genocide-the-police-ignore-an-obvious-conspiracy (accessed on November 25, 2022).

22. Jafri, Alishan and Naomi Barton, “Explained: ‘Trads’ vs ‘Raitas’ and the Inner Workings of India’s Alt-Right,” The Wire, January 11, 2022, https://thewire.in/communalism/genocide-as-pop-culture-inside-the-hindutva-world-of-trads-and-raitas (accessed on November 25, 2022).

23. Roy, Divyanshu Dutta, “Outrage As Muslim Women Listed On App For ‘Auction’ With Pics Again,” NDTV, January 1, 2022, https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/bulli-bai-app-revives-sulli-deals-row-outrage-as-muslim-women-listed-on-app-for-auction-with-pics-again-2683879https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/bulli-bai-app-revives-sulli-deals-row-outrage-as-muslim-women-listed-on-app-for-auction-with-pics-again-2683879 (accessed on November 25, 2022).