Global hunger is now more a problem of price than availability

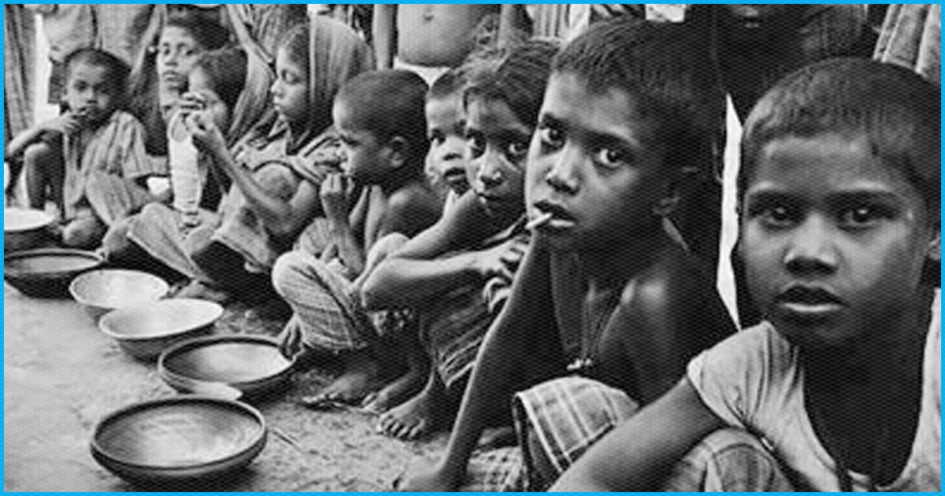

As always, women and children are the worst affected

By Avantika Chilkoti: International correspondent, The Economist

THE WORLD is entering 2023 in a hunger crisis. The World Food Programme (WFP), a UN agency that co-ordinates the distribution of food aid, reckons the number of people facing acute food insecurity jumped from 282m at the end of 2021 to a record 345m in 2022. As many as 50m people will begin 2023 on the brink of famine. And with governments still reeling from the covid-19 pandemic and grappling with slowing economic growth, many of those people could be starving in the coming months.

Until now, the problem has largely been spiralling prices rather than availability. Russia and Ukraine were among the top five global exporters of barley, maize and sunflower products in the world. So when war broke out, supplies of many staple foods were seriously affected. The countries worst affected were among the poorest in the world. Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, for example, relied on Russia and Ukraine for over 40% of their wheat imports. But the effects were felt everywhere. Global food prices soared as other countries, including Argentina and India, responded with trade restrictions. Emergency-relief efforts everywhere were hit because the WFP usually buys half of the wheat it distributes from Ukraine.

As many as 50m people will begin 2023 on the brink of famine

As the war rolls on, shipments from Ukraine have restarted and then faced an on-and-off blockade. Weak economic growth is weighing on demand. And, in some areas, inflation is starting to ease. The food-price index of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), which measures the monthly change in international prices for food commodities, has fallen gradually from its all-time high in March 2022.

António Guterres, the UN’s secretary-general, has warned that the world may shift from struggling with food-price inflation to simply not having enough food. Production of nitrogen fertiliser has collapsed as Russian exports of natural gas, a crucial ingredient, are squeezed. Farmers are using less fertiliser, switching crops and cutting production.

In 2023, people will go hungry for many different reasons. In conflict zones, such as Afghanistan, Ethiopia and Yemen, farming will be disrupted. Climate change means extreme weather events, like the floods in Pakistan and drought in the Horn of Africa, are becoming more common. Elsewhere, including rich countries like America and Britain, and large food-producing nations like Brazil and India, the problem is simply poverty. A mix of high inflation and a slowing global economy means many people will struggle to pay for the food they need.

The consequences of food shortages are grim. Going hungry raises the risk of chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes. Malnutrition does not just mean people eat too little and get thin. Particularly in cities, those who cannot afford nutritious meals buy cheap, packaged foods instead, and the poor are increasingly in danger of obesity.

Women are worst affected. They are more likely to be poor and to forgo food in order to feed their families. The FAO says that in 2021, 31.9% of women in the world were moderately or severely “food insecure” compared with 27.6% of men, and that gap is widening. A survey by Care, an NGO, shows how gender inequality and food insecurity collide. In Somalia, men said they were eating smaller meals, but women said they were skipping meals altogether. The report quotes a woman in Nigeria. “We have reduced the amount of food for everyone,” she says, “except my husband who is the man of the house.”

In children, hunger stunts brain development and reduces immunity. Just a few months of poor nutrition in childhood can reduce a person’s hopes of living a healthy, productive life. In a nursery for underprivileged children in São Paulo, the headteacher, Claudia Russo, sees more and more infants arriving for breakfast in the morning having eaten nothing since the lunch the nursery provided the day before. Those children are smaller, sicker and slower as a result. For them, the effects of the current food crisis will linger long after supply chains have been rebuilt and food prices have fallen.■

Avantika Chilkoti: International correspondent, The Economist

This article appeared in the International section of the print edition of The World Ahead 2023 under the headline “No food on the table”

Leave a Reply