“We have lost everything. Who has reaped? still, we are displaced in our freedoms” are the opening lines of the poem ईरपाल (erpal), meaning grievance, by local Koli poet Shahir Pundalik Mhatre; documented by the Tandel Fund of Archives, an archival project run by artists Parag Tandel and Kadambari Koli. The poem hallmarks the many years of displacement of the Kolis of Bombay, and the reclamation of their lands by the city’s industries. The city’s earliest inhabitants, its vibrant fisherfolk, are now fighting a long battle with their own home.

By Saachi D’Souza

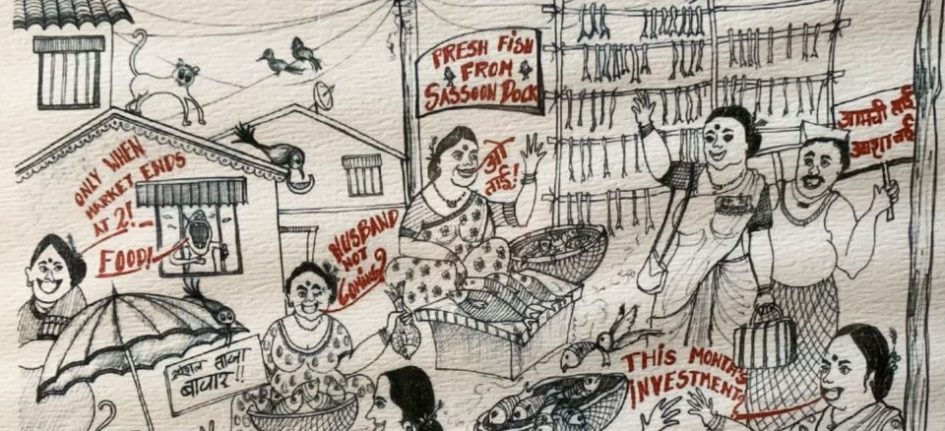

Morning travels in the Mumbai local trains are usually marked by chatters, sometimes quarrels while entering, between Koli fisherwomen, all carrying their daily stock. Most commuters remain unbothered by the seafood that accompanies their daily travels, and even those who are vegetarian eaters – some even staunch – manage to surrender themselves to the smells and sights of fish. One might argue that this is social conditioning, but it is important to note that Koli women for centuries have refused to lay their guards down. Tandel Fund of Archives (TFA) often centers them in their documentation of the community, since Koli women are instrumental in the economic distribution of fish in the city and interact with urban folk every day.

The women that make the community

Originally termed ‘Backward Class’ by the British, Kolis are considered as a lower-caste community in the city, placing the women in a social context that is structured not only by gender but caste dynamics.

Although Koli families are typically matriarchal in nature, with women engineering the cleaning, cutting and supplying of fish in female-dominated fish markets, the city’s decisions to demolish fish markets and evict Kolis away from the city renders many helpless. Over time, it might seem that the otherwise natural juxtaposition of the Koli women and the urban population has become a bother to developing industries in the city.

In a video clip of a woman protesting the State’s negligence towards their livelihoods, Tandel Fund of Archives captions it as ‘Stormy voice of Koli women’, alluding to their loudness that echoes in the city. Mumbai is widely marked by this voice; it is characteristic of the women that navigate the city’s landscape in ways unimaginable to many. TFA founders Parag and Kadambari embarked on this journey to claim Mumbai’s history as theirs – the Kolis – towards understanding contemporary problems that, to the community, exist because industries silenced them for their own development. They establish TFA’s social media as a repository of knowledge and experiences of the Kolis. It is remarkably a decolonised museum space, moving away from the conventional four walls and allowing Koli history to be a lived one; driven and written entirely by the community, for the community.

A history of displacement

“The last fisher in our family was my grandfather, after which we moved to office jobs,” says Hari Gomoji, a Koli, residing in the Versova Koliwada. After his grandfather, the fishing tradition in his family ended, and successors adapted to industrialisation. This is now common among younger Kolis who are withdrawing from the practice.

As globalisation hit Mumbai, so did the rise of the Maharashtra Industrial Development Corporation (MIDC), taking control of and marking several Koliwadas that, until then, were enjoying the benefits of fishing in smaller creeks and clear waters. “Once the fishing in the creeks stopped, there were no alternative livelihoods for such a large community,” says Ganesh Nakhawa in the podcast ‘Marine Lines with Raghu Karnad.’ Ganesh, a Koli, was addressing the rapid decline in fishing practices after industries started discarding untreated sewage in the creeks that fisherfolk depended on. Industries were also responsible for the large-scale displacement of Koli families forced to move away from the coast.

Historically, the subjugation of the community was established with colonisation in the country. The reclamation of their lands also included an attempt to alter customs according to colonial rule, and much of this was gendered. The Tandel Fund of Archives (TFA) released a series of ethnographic visual material, tracing the history of the community to archive indigenous history in Mumbai, and as part of the series shared old images of Koli women whose traditional, everyday clothing included the Kaashtha saree draped below the waist, and torsos almost always uncovered. This was designed for functionality until colonisation introduced the conservative blouse and imposed taxes on women who refused to conform. The advent of the British and Portuguese along the coasts seized agency from indigenous communities like the Kolis, who were left at the mercy of their power and Eurocentric ideas of bodies.

The need to archive

TFA asks itself and an audience – what is a decolonised museum? Perhaps it is documenting Kolis as people who still live, sharing a community through its food, or perhaps it is asking questions, regardless, TFA exercises agency through their work and through a continued engagement with the community. Situated in the Chendani village of Thane, they’ve organised pop-museums to discuss Koli traditions that are at the edge of ruin, like the specific Son Koli dialect and artisanal fishing practices that have largely been replaced by commercial fishing.

Frequently centering his mother as the harbinger of history and memory, Parag repeatedly shares her relationship with fish, and the relationship of Koli women with fish, which is unparalleled. The intimacies that they share with other women and themselves are visibly transferred in their treatment of fish, which is slow and careful, defined by touch. Parag’s photos display the use of hands as sensory feedback: a practice that evokes learnt history of a community. The fight against industries also includes slowly forgotten aboriginal Koli recipes, and practices around fish that to urban Mumbai are largely unknown. Indegenous recipes of fish are seldom discussed, and in the context of overfishing and exoticisation of fish, TFA is bringing an audience back to the home; where fish is a symbol, deeply personal and political.

Remembering history

Standing at the forefront of the business, Koli women have always carried the community’s history and legacy through practice. Much of the community’s oral history is rooted in folk songs that were directed by the women, who wrote and performed them. The archival of such traditions becomes doubly important, since, as Parag puts it, most of the oral history is lost, and the role of women in the community is dominated by patriarchal control over the livelihoods of the Kolis.

TFA maintains its archive through materials. From fishing nets used for artisanal fishing, tools used to cut and clean fish, to the navigation of spices required to cook Koli food, memories are built through these experiences both tangible and intangible, and TFA’s work includes them all. Not hiding from development but critiquing it, Parag also encourages the community to evolve with time but preserve its identity.

Courtesy : Citizen Matter

Leave a Reply