The folk who put food on your platter

PARTH M.N.In 2009, senior journalist P Sainath released a documentary called ‘Nero’s Guests’ on the agrarian crisis in India. It concludes with Sainath’s speech, in which he shares a piece of ancient history involving Nero, the infamous Roman emperor, whose reign witnessed a fire that destroyed half of Rome in AD 64.

When Rome burned and Nero could not control the fire, he decided to throw a party to divert people’s attention from it. The guests included all the elites of the time. But there was no provision to light up the huge garden supposed to accommodate the laundry list of guests. To conquer the problem, Nero summoned prisoners who were about to be hanged or were facing a life in prison and burned them alive in the periphery of the garden. The fire ensured the party went ahead without any difficulties.

As horrific as it sounds, Sainath makes an important point in the speech. “The problem is not Nero,” he says. “What did Nero’s guests do? Did they speak out against it?”

I remembered ‘Nero’s Guests’ this week after tens of thousands of farmers marched into Mumbai from Nashik. I covered the rally from the beginning. Majority of the responses I received on social media trivialised the march, for the red communist flags had swamped the visuals. It is political, they said, organised by “commies”, and does not reflect the agrarian distress. The “apolitical” middle class could not whine about traffic because despite walking the whole day, farmers decided to continue through the night and reached Azad Maidan before sunrise to avoid causing any inconvenience to students appearing for board exams on March 12.

Yes, it was organised by the Akhil Bharatiya Kisan Sabha, the farmers’ collective of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). Those leading the march were dedicated members of the party. But the ones walking behind them were ordinary farmers, tired of false promises. And there were over 35,000 of them from across Maharashtra, fighting for land rights, better rates, loan waivers and pension.

In the first 10 months of 2017, Maharashtra witnessed 2,414 farm suicides. Over a thousand of them were reported after the state announced the loan waiver, which was, at best, a decent attempt at innovating caveats. Reports suggest that the farm sector in the state is expected to post negative growth of 14.4 per cent.

The most important promise of setting minimum support prices at 1.5 times the production cost remains unfulfilled. In October last year, I travelled through the cotton belt of Parbhani district, where a farmer in his early 30s explained how the current pricing policy ends up digging their grave. He called his uncle, who farmed on the same 15-acre land until 2001-02. Both of them listed the production cost of their respective times and juxtaposed it with returns. It turned out the uncle roughly made Rs 11,000 behind an acre of cotton. The nephew, 15 years later, manages to earn around Rs 14,000. Now compare the rise in salaries of teachers or government servants in the past 15 years, he said.

I did. The Seventh Pay Commission increased the salaries of teachers by 22 per cent to 28 per cent from what they earned in 2008. MPs have received a staggering 1,250 per cent salary hike over the past two decades.

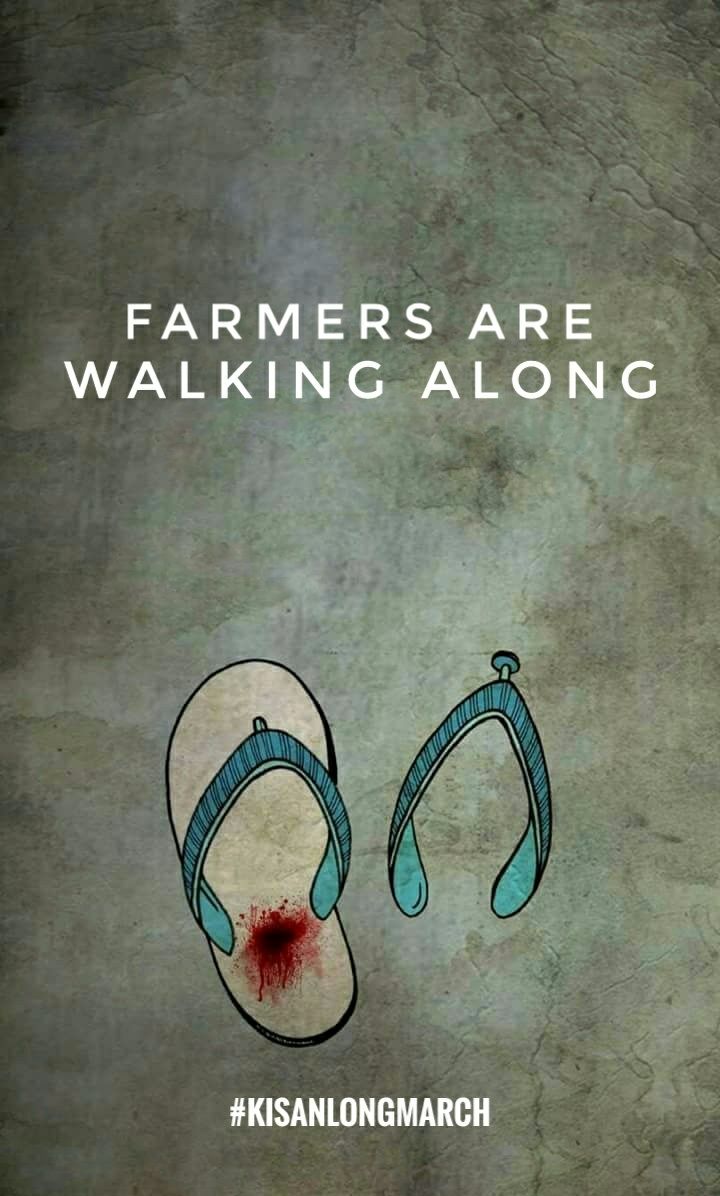

The CPI(M) merely channelised the resentment. If the Left could organise a march of 35,000 bogus farmers, they wouldn’t be paying Rs 8,000 bucks a month to full-time members. Irrespective of whether one agrees with their ideology, deriding the march is mocking those who walked to Mumbai because their dear ones committed suicide due to indebtedness. Trivialising the rally is looking down upon the 60-year old tribal woman who lumbered for seven days in scorching heat, leaving her labour work behind. If she had stayed back, she would have made around Rs 600 rupees and avoided the expenses she incurred during the protest. Yes, the farmers participated on their own expenses, trudged 170 km with injuries and blisters.

However, the insensitivity of the section of urban centres is more unsurprising than deplorable. Though some groups in Mumbai extended a heartwarming welcome to the protesters by offering food, water and biscuits.

In August 2015, Nashik had been prepping for the Kumbh Mela, for which Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis diverted 3 TMC water for the royal dip of pilgrims. However, it was diverted from the agrarian region of Marathwada, which had been suffering from acute drought. I was in Jalna at the time, covering farmers climbing down their parched wells, digging at the bottom until a muddy puddle of water formed, which they used to fill their empty pots. Merely 240 km away, thousands of people were getting drenched, supposedly washing off their sins.

In June 2017, farmers had declared a strike in Maharashtra, where they threw away their vegetables and milk on the road to express their anger. At the same time, a WhatsApp forward went viral. The message listed celebrities like Sachin Tendulkar and quoted the love and respect they have towards their profession. The message ended with a sarcastic line: Please do not link this to the current farm unrest.

The proliferation of social media has contributed to the bitterness of farmers. The distance between Mumbai and Latur, for example, is no longer as much as it used to be. The apathy in Mumbai reaches Latur and contributes negatively. We cannot do much to alleviate the farm distress, but the least we can do is not aggravate it by passing loose comments sitting in our ivory tower.

The writer is a fellow with People’s Archive of Rural India, where he documents the agrarian crisis in Marathwada

https://epaper.timesgroup.com/Olive/ODN/MumbaiMirror/#

March 15, 2018 at 4:09 pm

The sharp divide between urban people and rural peasants is mainly because of elitist attitudes of urbanites. They do not observe closely sufferings of farmers who work tirelessly from gathering seds to raising crops despite adversities