by-Sania Muzamil

The history of women in the workplace over the last one hundred years or so has been a constantly evolving domain, affected and determined by the changing scenarios of global issues and international relations. As nations birthed through the tumultuous processes of wars and subsequent negotiations to prevent further wars and loss, the nature of the workplace and the ideal conceptualization of the work-force in almost all the sectors changed from a homogenized group of able masculine populace to a more blended group of diverse and varying human beings, including women.

To understand the concepts of work in terms of gender, we need to have a brief, but clear idea about what it means to be a ‘laboring’ body. It needs to be identified what kind of work merits a ‘reward’ (capital or other forms) and which ideology decides that and why.

Just like any other form of art, Films are a reflection of what goes on in the world around us. If we look at the larger and long-standing canon of visual texts available to us, barring a few, most of the mainstream films bring forth to us the very same stereotypical processes of ideation that are conveyed to us through other media. Throughout film history the representation of the ideas of work reproduce the same patriarchal notions that inform our lives in general.

In this piece we shall try and focus on two films that solely emphasize on women protagonists trying to navigate through and negotiate with the various forms of work and reproductive labor for sustenance and portray just an extension of the unpaid household labor that is seen as a natural duty of women across the world.

The first film is the 1974 film ‘Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore’, directed by Martin Scorsese that depicts in an extraordinary manner the life of a female character, who after the death of her husband tries to reconcile her need for a paying job with her deep and underlying passion for singing. As the story unfolds, the titular character Alice travels across the Southwestern United States with her 12-year old son looking for a job as a singer. What she faces is neither very unique nor surprising as it’s nothing but the inbuilt and deeply rooted patriarchal bias that looks at women merely as ‘sexual objects’ capable of work involving only their charming looks and/or emotional labor and not intellectual or physical work. Alice buys new, supposedly ‘appealing’ dresses and gets her hair done in order to look ‘attractive’ enough for a job.

The subtle and very nuanced undertones of how physical beauty is seen as the primary and necessary capability a woman can possess, without which she has no chance to survive brings to the fore the very problematic idea of woman’s place in public workplaces. A very accurate notion that women to this day are seen fit for what are termed as ‘pink-collar’ jobs that require emotional labor including dealing with one-to-one interactions and appealing to the ‘emotional’ side of the customers can be applied here.

After Alice has to leave her job as a piano-singer due to the aggressive behavior of a man she starts seeing, she takes up the work of a ‘waitress’ in an eatery where an evident ‘burnout’ of her co-workers is apparent due to the very demanding and underpaid labor- emotional and physical that these women are subjected to.

The public and private spheres of women are mostly merged together as they are expected to bring in the ‘emotional, nurturing touch’ to their work-place and it becomes impossible to differentiate between the two.

Although Films do portray the resistance women put up in their lives, yet the fact that films are manufactured and involve labor and are themselves part of the same patriarchal economic system that transforms them into a commodity vulnerable to the ‘male’ gaze cannot be ignored. Films are mostly turned into ‘ideologically-safe’ projectiles to appeal and cater to the male audience while female spectatorship is largely ignored. Female audiences are forced to take up the uncomfortable position of a ‘masculine’ perspective while viewing the film as is clearly seen when Alice is asked to turn around while looking for a job. However the very sharp and memorable retort by Alice that ‘she sings with her mouth and not her ass’ refusing to be commodified marks a brilliant moment of resistance and a demand to refocus on ‘intellectual’ labor that women are equally capable of doing.

Alice is looking for a job mainly to help sustain her child portraying how women’s work outside their homes is seen as an extension of the care-work instead of an expression of one’s own dreams and ambitions. Like most of the narratives the film ends with a very predictable and anti-climactic ending with Alice falling into the same trap that she aspired to run from.

This is in stark contrast to the subsequent film I shall be talking about.

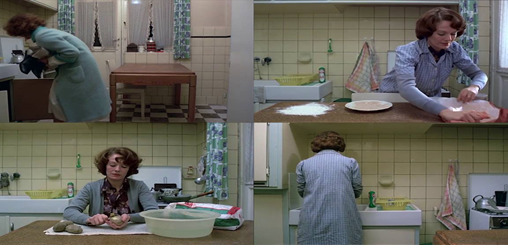

‘Jeanne Dielman, 23 Commerce Quay, 1080 Brussels’, directed by Chantal Akerman in 1975 is a meditative and brilliant masterpiece that accurately portrays the ‘double-shift’ women are subjected to and unravels the ritualistic and repetitive nature of the ‘unpaid, unacknowledged and invisibilized’ household labor of women, while at the same time bringing under the limelight the sexual labor that is mostly seen as exclusive to women as their bodies are seen merely as objects for catering to the sexual desires of men and inadequate for any other form of work. The whole film shows the daily household labor of Jeanne Dielman who very carefully and meticulously completes all the household work- peeling vegetables, cooking, shopping, cleaning, etc. while at the dinner-table her son Silvian reads silently.

The cinematic technique of using ‘real time’ for her household labor to focus on the indeterminate amounts of time women put in at home to serve their families shows how due to its repetitive, exhausting and unending nature, household labor becomes invisible and is not acknowledged as work that should be seen and rewarded. Rather it becomes drudgery; something that is an inherent duty of a particular gender and does not merit being talked about. On the other hand the sexual labor that Jeanne undergoes is given less screen-time and through this it’s determinate time-period is shown and although problematic, is a paid form of work.

Jeanne over days, is shown becoming careless about the accuracy with which she deals with her daily tasks and her tiredness due to the relentless repetition of her labor becomes apparent. She murders her client with a pair of scissors ending the laborious cycle that her life has become.

In their portrayal of women, films usually deal with melodrama showing the emotional labor that women are expected to undergo, yet the meaning of labor in terms of gender roles is seen persistently and stereotypically in most visual texts.

The idea of paid and unpaid labor needs to be rethought and restructured at the least not only because it’s unfair to women, but also because the whole notion of Capitalism runs upon the idea that only certain forms of labor can be viewed as work and shall be paid for, while all other forms are unproductive and are mere bolsters to prop up the existing structures and help able-bodied men to fulfill their ambitions and lead a productive, profitable life. Women’s labor in public spaces is seen as mere extrapolation of their household labor and is only meant as a supplement and not productive in itself.

Sania Muzamil advocates for equal gender and human rights, and calls for a free world for all. She has a postgraduate degree in English Literature from the University of Delhi and is currently studying and researching Gender perceptions and manifestations. She is currently interning at kractivist.org

Leave a Reply