Dhasal’s poetry, which was steeped in harsh words, attempted to translate the violent existence of Dalits and the oppressed to paper.

=

Unnato Mishra

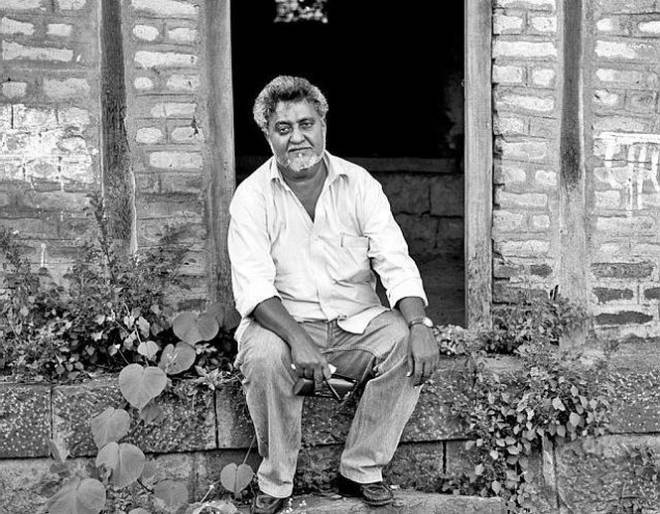

New Delhi: “Both my individual and my collective life have been through such tremendous upheavals that if my personal life did not have poetry to fall back on I would not have reached thus far. I would have become a top gangster, the owner of a brothel, or a smuggler,” said renowned Marathi poet and Dalit activist Namdeo Dhasal about his life and poetry.

Born in a Mahar family that are considered ‘untouchable’, in Pune, Dhasal’s poetry waged a war against all kinds of exploitation.

Author Sudhir Arora, in an article titled ‘Voicing Dalits: The Poetry of Namdeo Dhasal’, wrote that through his poetry Dhasal had launched “from the very start — single-handedly — a guerrilla war against the effete middle-class and sanitized world of his literary readers”.

According to poet Dilip Chitre, Dhasal’s poetry embraced all people discarded by society as useless.

Chitre, who is also the author of the biography Namdeo Dhasal: Poet of the Underworld, noted that his poetry talks about pimps, criminals, prostitutes, street urchins, gangsters, mujra dancers, labourers etc.

Famous Marathi playwright and critic Vijay Tendulkar even compared him with Tukaram, the famous bhakti saint-poet of Maharashtra.

On the poet’s 7th death anniversary, ThePrint looks at the life and works of Namdeo Dhasal who revolutionised Marathi Dalit literature.

Early life

About his early life, Dhasal wrote: “I was born/On footpath/ when the Sun was leaked/ and being dimmed/into the bosom of night”.

He was born on 15 February 1949 in a village in Pune. His father Laxman Dhasal moved to the city of Mumbai, to earn a living for the family and started working as a porter in a Muslim butcher’s beef shop in central Mumbai.

He lived in an area called Dhor Chawl and Dhasal’s youth was spent amid drug peddlers, smugglers, sex workers — and their life experiences feature prominently across his poetry.

He once described his life in these words: “I boozed. I visited brothels. I went to mujra dancing women’s establishments and to houses of ordinary prostitutes. The whole ambience and the ethos of it was the revelation of a tremendous form of life. It was life! Then I threw all rulebooks out. No longer the rules of prosody for me. My poetry was as free as I was. I wrote what I felt like writing and how I felt like writing.”

Dhasal never went to college, but read voraciously while earning his living as a taxi driver.

Evolution of his poetry and Dalit Panthers

Dhasal wrote nine anthologies of poems and several prose writings, including one novel.

However, his most celebrated work is Golpitha — his first poetry collection published in 1971, for which he received Soviet Land Nehru Award.

It took the Marathi literary world by storm for the harsh language used in it. Chitre described it as the ‘bibhatsa rasa’ (disgust). It talked about the plight of pimps, prostitutes, criminals and others on the margins of society.

A year later, in 1972, Dhasal formed the ‘Dalit Panthers’, a social organisation inspired by the American Black Panther movement, along with poet-activists J.V. Pawar, Raja Dhale, Arjun Dangle among others.

The Dalit Panthers was a result of Dhasal’s disillusionment with mainstream political parties and the rise of atrocities against Dalits in the 1960s. The organisation played a crucial role in Dalit politics throughout the 1970s.

The first wave of Dalit Panther protests in 1972 and 1973 brought Marathi Dalit poetry and fiction, in translation, to the middle- and upper-class audiences all over the country. And prominent among them was Dhasal’s poems.

His poetry revolved around the realities of Dalit life and the daily struggles faced by the community. Most of them are also marked by violent language to translate the violence that Dalits routinely faced.

In one of his poems from Golpitha, ‘Man, You Should Explode’, the element of destruction is clearly visible:

“Kill oneself too, let disease thrive, make all trees leafless

Take care that no bird ever sings, man, one should plan

to die

groaning and screaming in pain

Let all this grow into a tumour to fill the universe,

balloon up

And burst at a nameless time to shrink.”

But the same poem, however, was marked with hopeful tones later:

“After this all those who survive should stop robbing

anyone or making others their slaves

After this they should stop calling one another names

white or black, brahmin, kshatriya, vaishya or shudra.”

Dhasal imagined the role of sex workers and transgender people as radical activists and considered them capable of fighting their battle.

According to J.V. Pawar in 1971 Dhasal had even organised a ‘morcha’ of people involved in sex work and transgender people – both groups were invisible in the political realm – from Kamathipura towards Chaityabhumi. If one who knows about structural social reality thinks about this action symbolically and pragmatically, this is a journey from dirt to self respect.

In his interview with Nikhil Wagle on IBM Lokmat, Dhasal mentions he used to write ghazals but had to abandon it as he did not find any relational reasoning within the everyday lived experiences he or his community had. It is said that Dhasal gave new fame to the Marathi language, but one has to go beyond this limited acknowledgement. From his Golpitha (1973) emerges the shocking social realities of Mumbai. Tuhi Iyatta Kanchi, Tuhi Iyatta? (‘What Grade Are You In, What Grade?’, 1981), along with his other anthologies of poems, several prose pieces and one novel gave a new vocabulary and new grammar to the Marathi language. By riding over established Brahmanical Marathi, Dhasal through his poetry offered critical theory for a critical society.

In his poem “Kamathipura” compiled in the collection Tuhi Iyatta Kanchi, Tuhi Iyatta? he writes:

“गोड किंवा खारट

विषाची चव घेण्यास जुंपल्यात इथं रांगा.

शब्दासारखे इथे मरणदेखील आले आहे भरून

बस्स, थोड्या वेळात इथे सरी कोसळू लागतील”.

(sweet or salty

there are queues here in competition to taste poison

unlike words death has also come as blocked up

enough, in a sometime there will be heavy showers) [rough translation by author].

This above stanza depicts the life and social relations in Kamathipura, a area where a number of people come to see sex workers. In the crowd, nobody will be visible. This is a story of every red light area and its narratives that have mostly remained invisible to society at large.

Through his social and political commitment, Dhasal introduced a new world to mainstream literary culture. Although there are few works available around Dhasal’s poetry, they have remained limited to anger, body and the city. There is no in-depth study available which explores the critical pedagogy that Dhasal has formed through his experiences and writings. This critical pedagogy of Dhasal is poetical, political and socio-culturally rooted in humanism and the necessity for dismantling structural inequalities.

Satish Kalsekar, Dhasal’s close friend and fellow poet, pointed out how his poetry evolved, “Namdeo’s poetry in the early period seems more aggressive whereas in the later period, it becomes more wise and appears more mature.”

Dhasal was awarded the Padma Shri in 1999 for his achievements in Marathi literature. He was conferred with the Maharashtra State Award for literature four times — in 1973, 1974, 1982 and 1983.

The Sahitya Akademi also presented him with the Golden Lifetime Achievement Award in 2004.

After a long debilitating battle with colon cancer, Dhasal died in Mumbai at the age of 64 on 15 January 2014.

courtesy The Print

Leave a Reply